Accessibility Accommodations on the National Physical Therapy Examination: An Exploratory-Descriptive Qualitative Study

By Katherine Franklin, PT, DPT, PhD; Carolyn P. Da Silva, PT, DSc, NCS; Wayne Brewer, PT, PhD, MPH, OCS, CSCS; Rupal M. Patel, PT, PhD

Abstract

Background and Purpose: Physical therapy educators are witnessing an increase in the number of students with disabilities requesting accommodations on the National Physical Therapy Examination (NPTE). Little is known about how the process of seeking these accommodations impacts applicants. The purpose of this qualitative study was to examine the lived experiences of NPTE candidates who navigated the process of applying for testing accommodations on the NPTE.

Subjects: Recent NPTE candidates (2017-2022) were recruited via the American Physical Therapy Association Academy of Education LISTSERV. Exclusion criteria were candidates who did not request disability accommodations and those who took the NPTE prior to 2017.

Methods: This study utilized an exploratory-descriptive qualitative research method with purposeful sampling to examine NPTE candidates’ experiences with the process of applying for testing accommodations. Data was collected using semi-structured interviews, and data analysis was conducted using thematic structural analysis.

Results: The authors conducted five interviews. Structural analysis yielded the following themes: 1) NPTE candidates who apply for accommodations face the “disability tax;” 2) “invisible disabilities” impact individuals seeking accommodations throughout their educational and early professional careers; and 3) entry-level physical therapist educational programs affect the NPTE testing experience for those seeking accommodations.

Discussion and Conclusion: The current process of applying for NPTE accommodations places a heavy burden on candidates, which disproportionately impacts some candidates more compared to others. This information sets the foundation to drive future actionable strategies that address the structural barriers impacting the NPTE testing accommodations process.

Key Words: physical therapist education, disabilities, testing accommodations, National Physical Therapy Examination, qualitative research

Introduction

In 2022, discussion took place on the American Physical Therapy Association (APTA) Academy of Education LISTSERV regarding the testing accommodations process for candidates preparing to take the National Physical Therapy Examination (NPTE) (multiple contributors, APTA Academy of Education LISTSERV, February 2022). Individuals participating in the discussion, who primarily self-identified as educators in entry-level physical therapist education programs, shared the experiences of current students and recent graduates navigating the process of applying for accommodations. One common thread through this discussion was the fact that the process for securing accommodations varies across different states. Some educators shared that they knew candidates who received accommodations throughout their undergraduate and professional school careers but were then denied those same accommodations on the NPTE. Many candidates went through the appeals process, but were still denied accommodations. Some candidates even chose to apply for accommodations through a different state than the state in which they both lived in and intended to practice. Then, they retroactively applied for licensure in the state in which they intended to practice. This rich dialogue highlighted an issue within the field of physical therapist education: inequities in the process of applying for NPTE testing accommodations.

This discussion also sparked a movement that has since led to the adoption of HOD-P08-22-14-18: Equitable Accommodations in Physical Therapy, an APTA House of Delegates position statement emphasizing the importance of promoting equitable processes for the securement of reasonable accommodations through physical therapist education and practice, including on the NPTE.1 Despite these initial steps toward promoting improved equity for testing accommodations on the NPTE, little is known about how the process of seeking these accommodations impacts applicants. The purpose of this study was to examine the lived experiences of NPTE candidates who navigated the process of applying for testing accommodations. Thus, the research question was: “What are the experiences of NPTE candidates who applied for testing accommodations?”

Literature Review

Physical therapists (PTs) and physical therapist assistants (PTAs) play a critical role in the management of disability. However, a disconnect exists between the field of physical therapy and the disability community at large. Only 5% of surveyed student PTs report having a disability,2 compared to 26% of the United States adult population3 and 11% of all graduate students.4 Furthermore, many in the disability community have been critical of the role that rehabilitation professionals play in conceptualizing and treating disability.5,6 Ableism, or disability bias, has been defined as “a pervasive system of discrimination and exclusion that oppresses people who have mental, emotional, and physical disabilities… [and] operates on individual, institutional, and societal/cultural levels.”7,p198 Ableism is pervasive within our culture and within healthcare.8 This bias is reflected in physical and social accessibility limitations in healthcare settings9 and educational institutions,10 including the accommodations process.11

Overview

This section will provide a brief overview of testing accommodations in physical therapist education and review the current process of seeking accommodations on the NPTE.

Testing Accommodations in Physical Therapist Education

While the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 provides federal civil rights protections for individuals with disabilities and prohibits discrimination against those individuals in employment, education, transportation, and physical spaces open to the general public, its full implementation remains a challenge in healthcare and higher education. Individuals with disabilities in entry-level physical therapist educational programs have reported inconsistencies in the provision of educational accommodations.12 Additionally, standardized procedures for the selection, notification, and implementation of accommodations in clinical education does not exist in entry-level physical therapist educational programs.13 Physical therapy faculty report challenges in determining and implementing reasonable accommodations for students with disabilities,14 and describe struggling to reconcile providing accommodations for students while remaining focused on the health and safety of the patients and clients these students will eventually manage.15

The number of individuals with disabilities applying to entry-level physical therapist educational programs is increasing,16 as is the number of NPTE candidates seeking testing accommodations.17 While there is insufficient data examining trends in the number of entry-level physical therapist students who identify as having a disability, there is likely a connection between increasing numbers of applicants with disabilities, students with disabilities, and NPTE candidates seeking accommodations. In combination with increasing numbers, the visibility of individuals with disabilities within the profession is also improving, as evidenced by the formation of the Disability Justice and Anti-Ableism Catalyst Group within the APTA Academy of Leadership and Innovation.18 Given the evolving landscape of disability representation in physical therapist education, relevant stakeholders (eg, physical therapist faculty, university administration, NPTE leadership) must also adapt to better support the needs of those navigating the accommodations process.

NPTE Testing Accommodations Process

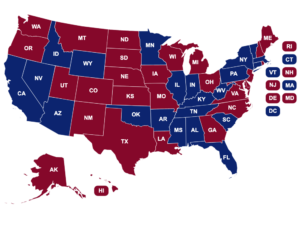

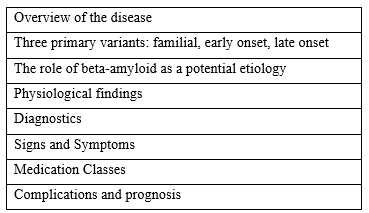

Managing the requests for accommodations on the NPTE is an evolving process that varies from state to state. At the time of this manuscript’s writing, requests for testing accommodations in 28 states were managed directly by the Federation of State Boards of Physical Therapy (FSBPT) while the remaining 22 states independently manage requests by their state’s licensing authority (Figure 1).19

Figure 1. Map of the United States of America. Maroon indicates states in which testing accommodations requests are managed by the Federation of State Boards of Physical Therapy (n=28). Navy indicates states in which testing accommodations requests are managed by the state licensing authority (n=22).17 Information current as of January 2025.

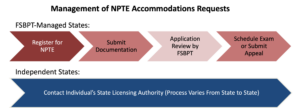

For candidates in FSBPT-managed states, individuals first register for the NPTE, then assemble and submit supporting documentation20 along with the FSBPT Accommodations Request Form.21 The FSBPT reviews the request for accommodations and communicates their decision. If denied, candidates can submit an appeal.22 If approved, candidates receive an Authorization to Test letter reflecting those accommodations and then schedule their exam.

Available NPTE accommodations include:

- Testing in a separate room

- Allowing extra time on the exam

- Using a reader or scribe

- Using Zoom text magnification

- and other accommodations.19

For those in independent states, the request process varies significantly on a state-by-state basis. For example, the Physical Therapy Board of California (PTBC) requires candidates to complete a multi-page Disability Accommodation Request for Examination Form23 that includes a professional verification of need for accommodations by a qualified evaluator and a list of accepted standardized psychometric test results performed to diagnose the disability. This information is accessible on the PTBC’s website,24 and is listed first in search results for “accommodations.” The accommodations request form is also listed under “Applicant Forms” in the “Forms” tab of the website.25

In contrast, the process in Connecticut is unclear. No forms are immediately available on the Connecticut State Department of Public Health’s Physical Therapist Licensure website,26 nor do any relevant results populate when searching for “accommodations” using the website’s search feature. These inconsistencies make it more difficult for candidates in some states to apply for accommodations than in others, thereby contributing to inequities within the accommodations application process (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Graphic demonstrating the differences in the management of NPTE accommodations requests between states in which requests are managed directly by the FSBPT and those where requests are managed by the state’s licensing authority.

Methods

Research Framework

This study utilized an Exploratory-Descriptive Qualitative (EDQ) research approach with purposeful sampling of participants. The EDQ research approach is based on the work of Stebbins27 and Sandelowski,28,29 and is used to both explore and describe aspects of healthcare practice, education, and policy when the topic under investigation has received little previous attention.30 EDQ research recognizes the subjective nature of the problem being examined and highlights the different individual experiences that participants have.31 EDQ research is used to uncover the ‘who, what, and where’ of events or experiences.30

Purposeful sampling is considered an appropriate strategy in EDQ, allowing the researcher to recruit participants who can provide the information needed to address the study’s aims.30 For data collection, the use of semi-structured interviews is recommended, in conjunction with the collection of participant demographics to generalize who is feeling what about whom, and when and where the action is taking place. Data analysis for this study followed the six-phase thematic analysis process described by Braun and Clarke.32 This six-phase process begins with the data being transcribed and the researcher familiarizing themselves by reading and re-reading the transcript and noting their initial ideas. Relevant data is coded in a systematic fashion across the data set, and codes are then collated into themes. Themes are then reviewed, both in relation to the codes as well as in relation to the data as a whole. Themes are defined and named and a report is produced that relates the themes back to the research question(s) and any relevant literature.32

Best practice in disability studies literature includes the researcher stating their own relationship to disability.33 The principal investigator (PI, KAF) currently identifies as a non-disabled ally to the disability community and as the sibling of a person with congenital disabilities. The PI has taken graduate-level coursework on the social constructs of disabilities and earned a post-baccalaureate certificate in diversity, with an emphasis on disability as a form of diversity. The PI’s clinical background area is the neonatal intensive care unit, where they worked to support individuals with disabilities and their family units. The PI is a Certified Aging-in-Place Specialist through the National Association of Home Builders and owns a consulting company focused on designing physical spaces accessible to those of all ages and abilities. These educational, clinical, and personal backgrounds provide the lens through which the PI views disability.

Sample and Interviews

Texas Woman’s University Internal Review Board approved the study, which was completed as part of the PI’s graduate coursework. Participants were recruited from NPTE candidates who took their licensure exam between the years 2017 and 2022, via an email sent by the PI to the APTA Academy of Education LISTSERV. Academy members were encouraged to forward the email to recent graduates from their respective educational programs. The recruitment email included a link to an anonymous survey (PsychData, LLC, Irving, TX) that collected demographic information, including participants’ self-reported disability status. The survey did not include an explicit definition of disability, so participants were free to interpret the construct of disability in the way in which they most closely self-identified.

When self-identifying, participants were prompted to select all that apply from the following disability types:

-

- Behavioral

- Emotional

- Learning

- Mental

- Physical

- Sensory

Upon completion of the survey, participants were invited to continue participation in semi-structured virtual interviews.

Interview exclusion criteria were those who:

-

- Did not request testing accommodations on the NPTE.

- Did not self-identify as having a disability.

- Did not want to participate in a virtual interview lasting less than one hour.

- Took the NPTE earlier than the year 2017.

Semi-structured interviews lasting less than one hour took place virtually and were held on secure video format over Zoom with the PI, who presented their identity to participants as a physical therapist and graduate student with research interests in the intersection between physical therapy and disability studies.

An interview guide was created, focusing on participants’ experiences as individuals with disabilities seeking accommodations on the NPTE, with questions focused on describing a typical day in their life as well as describing their experiences with accommodations (Appendix 1).

The PI, aided by the interview guide, used open-ended questions in combination with data gleaned from the demographic survey to explore candidates’ experiences navigating the NPTE. After interviews were completed, audio recordings were transcribed using NVivo software (Lumivero, Denver, CO) and all personal information was de-identified. Field notes were combined with audio transcriptions to provide additional context to the data collected (including both non-verbal and paraverbal communication: tone, pitch, and cadence).

Process consent was obtained at multiple points throughout the study, as described by Munhall.34 Accessibility accommodations were made as needed during semi-structured interviews, including offering breaks to participants, providing questions in both written and verbal forms, and enabling closed captions. Participants were offered the opportunity to review the transcript of their interview, a form of respondent validation which is used to help establish trustworthiness in qualitative research.35

Data Collection and Analysis

Data collection and analysis followed Hunter, McCallum, and Howes’ approach to EDQ research,30 with the goal of exploring and describing the process of applying for testing accommodations on the NPTE. This approach was deemed the most appropriate method to explore a relatively unknown phenomenon that has not yet been studied in physical therapy educational research by providing insight into NPTE candidates’ perceptions and experiences of requesting testing accommodations. The decision to conduct this research following EDQ methodology was also made in order to test the feasibility of implementing semi-structured interviews for data collection and thematic analysis of results in the topic area, which will help guide the PI’s future graduate coursework.

Results

Study Participants

A total of seven individuals responded to the survey. One survey participant did not formally request NPTE accommodations because he did not believe he would receive the accommodations in time for his test, and thus was excluded from the study. Another did not respond to the PI’s follow-up request for an interview. Therefore, five interviews were conducted, which took an average of 24 minutes (range: 19-30 minutes). Participant demographics are shown in Table 1. States represented included a mixture of those where accommodations requests are managed by the FSBPT (n=3) and those where requests are managed by individual state jurisdictions (n=2). Survey participants included candidates from Arizona, Massachusetts, New York, Texas, and Virginia. Four out of five participants reported multiple disabilities, with representation across the following disability categories: emotional, learning, and sensory. All participants graduated and took the NPTE between 2017 and 2021.

Table 1. Demographic Information of Study Participants

Structural Analysis

During structural analysis, key sections of the interview transcripts were highlighted and condensed down to summary statements, which were further condensed and organized into themes. Three major themes emerged during structural analysis:

- NPTE candidates who apply for accommodations face the “disability tax.”

- Invisible disabilities impact individuals seeking accommodations throughout their educational and early professional careers.

- Entry-level physical therapist educational programs and universities at large affect the NPTE testing experience for those seeking accommodations.

Theme 1: Disability Tax

The first theme to emerge was that of NPTE candidates who apply for accommodations facing the disability tax through the additional labor and costs associated with securing NPTE accommodations for individuals with disabilities. In this context, the disability tax encompasses compiling medical and academic documentation, completing the application itself (including any appeals associated with an application denial), and then scheduling the exam. The disability tax is highlighted in the following statements made by Participants 2, 3, 4, and 5.

Participant 2 expressed frustration with the availability of information on seeking accommodations and suggests the creation of a more centralized, straightforward resource:

“I found it very intimidating to try and navigate who I should be talking to and who needed to receive what and by when. And just to make sure that everything was in line for me to successfully request the accommodations and get them approved in time for the exam. So, I very much felt like everything was on my shoulders to advocate for myself and really be organized and on top of things so that I didn’t screw this [application] up. I wish that there was some kind of website or centralized resource to reference for disability-type accommodations, because I felt like it was very much under wraps. Not that it was intentionally so, but in terms of ADA stuff and wanting to make accommodations accessible in a straightforward manner to people who need them, who might have difficulty accessing the resources to get the accommodations in the first place. Wouldn’t it make sense to have a resource that was readily available for such things?” (Participant 2).

Participant 3 shared a similar request for a more streamlined, uniform process:

“Every state is different, and I wish it was more uniform because there’s a lot of confusion, I think, when it comes to what the steps are. Overall, you just have to make sure that you’re doing your research and you’re asking for help in order to get your accommodations and to have the process be streamlined. And you just need to give yourself extra time because you’re relying on other parties like your psychiatrist and working with your state.” (Participant 3).

Participant 4 expressed frustrations with the inefficiencies associated with having to call to schedule their exam because of their accommodations, as opposed to being able to register online as their peers testing without accommodations could do:

“I was surprised it was what came after that was difficult. I know from my friends who didn’t have any accommodations when they went to schedule their NPTE, they went online, and they picked a day in a location and click! They were registered. And that was it. But because I had accommodations, I couldn’t go online. I had to call. And I sat on the phone, because I took the boards twice, both the first time and the second time I sat on the phone for like a total of four or five hours on hold. I think that that was probably the most frustrating thing because I lost all of that study time. I had all of that frustration. I would go into work feeling so defeated already because I didn’t study. I didn’t get it scheduled. My bosses were like, When’s the test? And I was like, I still don’t know because I sat on hold for an hour and a half and never got through.” (Participant 4).

Participant 5 recounts how frustrating it was to spend the time, money, and effort to undergo formal testing, only for their accommodations request to be denied:

(Referring to the FSBPT): “I was not supported. It was extremely frustrating. I hope you put these in quotes. I was disappointed in their rationale, and I want to pull up the email now thinking about it because it was so infuriating. I had a PhD psychologist do like 16 hours worth of testing and wrote up a report specifically to receive accommodations on a national level that were rejected. So I didn’t feel like they were at all helpful…nor did they take the recommendations from three different doctors I saw seriously. So no, I was not supported on the NPTE.” (Participant 5).

Theme 2: Invisible Disabilities

The second theme to emerge was the concept of invisible disabilities, where participants described the unique challenges associated with the unseen nature of their disabilities. Study participants discussed the major impacts that their disabilities had on their lives, which for all participants occurred primarily during their education. To a lesser extent, some also reported an impact on their work, family, and social lives. Participants 2, 3, and 4 expanded on their invisible disabilities in the following statements:

Participant 2 describes their experience with the invisible nature of their disability:

“I’ve been told on many occasions that if people didn’t know that I had a disability, they would not suspect one.” (Participant 2).

Participant 3 expands on this by discussing the shame they felt when their classmates learned of the educational accommodations associated with their invisible disability:

“And there’s a lot of shame with [accommodations] because people are like, oh, where are you going? Where did you take that test? Did you miss the test? And the other thing is I took longer to get through grad school so some people were like… what happened that you couldn’t hack it and you had to take an extra year? And then it’s like, well, I had some mental health stuff, and it’s a lot easier to explain physical issues versus having mental health stuff.” (Participant 3).

Participant 4 shared their experience with a late diagnosis due to the invisible nature of their learning disability, which was not recognized until they began their entry-level physical therapy program:

“I got diagnosed with my learning disability pretty late in life. And that being said, I never really felt like it held me back in anything because I wasn’t really aware of it until I was. So growing up, I never had any issues grades-wise, I always was a good student, but I always felt like it took me a really long time to do the things that other kids were doing really quickly. And I never really tossed it up to anything other than maybe it just took me a little longer to read. So, once I hit grad school and I was studying nonstop 11, 12 hours of material. And for the first time in my life, I was running out of time on tests and like actually failing out. And I didn’t really know what to think of that because it was the hardest I had ever studied and the worst I had ever done.” (Participant 4).

Theme 3: Institutional Support

Most participants reported feeling well-supported by their educational programs and institutions in utilizing testing accommodations throughout their entry-level physical therapist curriculum. However, some programs and universities were more helpful than others in navigating the process of applying for accommodations on the NPTE. The third and final theme to emerge relates to participants’ perceptions of institutional support for seeking testing accommodations on the NPTE, described in the following statements by Participants 2 and 3.

Participant 2 shared that their program faculty and leadership were unfamiliar with the process of seeking accommodations:

“But for the most part, the people in the department themselves and even the head of the program wasn’t really sure (to the best of my recollection, anyway), what the best approach was to apply for [NPTE] accommodations.” (Participant 2).

Participant 3 echoed these experiences with faculty being unfamiliar with the process:

“I guess the biggest thing is there’s a lot of faculty that do not know the steps involved for [NPTE] accommodations. One instructor told me that it was the Prometric Center that decided accommodations, and I was like, no, that’s the state.” (Participant 3).

Participant 3 also shared how having support from their university’s disability support services office was helpful in navigating the accommodations process, and helped to counteract frustrations with their department’s faculty being misinformed:

(On applying for accommodations on the NPTE): “Yeah, I felt like I was very supported. I felt like my accommodations person [at my university] gave me very detailed information on what I needed to include. He was also very much like, send me the forms and I will see what you filled out. And I’ll tell you whether we need to make corrections because you need to make sure that you include how you struggled and why this is important and why you need it.” (Participant 3).

Discussion and Conclusion

This is the first study utilizing an EDQ approach in entry-level physical therapist education that examined the lived experiences of candidates seeking accommodations on the NPTE. These findings are consistent with the literature on barriers surrounding accessibility and accommodations in higher education11–15 and provide a first-person perspective specific to how this process impacts NPTE candidates navigating the testing accessibility accommodations process.

Theme 1 showed that participants in this study expressed feeling high levels of pressure and devoting significant time and effort to complete the process of applying for NPTE accommodations, a novel finding that has not yet been previously reported. This theme is consistent with how the disability tax is conceptualized in the literature.35 The term “disability tax” was introduced in 2022 and refers to the multiple additional steps that individuals with disabilities must take beyond what non-disabled individuals do in order to secure equitable access to resources.36 This term was adapted from the concept of other taxes impacting marginalized populations, including the minority tax, which encompasses the emotional, economic, and intellectual labor imposed upon people of color who must navigate a predominantly white culture in the workplace.

In framing the concept of the disability tax within the broader construct of disability bias in physical therapy, we are confronted with the irony of a profession supposedly dedicated to advocating for patients with disabilities while simultaneously excluding individuals with disabilities from their full participation in the profession itself.

Participants expressed a desire for improved consistency across jurisdictions as well as the development of a centralized informational resource to streamline the application process. Participants also expressed frustrations with inefficiencies in exam scheduling, primarily related to having to call to schedule their examination time instead of being able to schedule online like those without accommodations can do.

Theme 2 showed that the invisible nature of learning, sensory, and emotional disabilities can be a complicating factor when navigating the accommodations process. “Invisible disabilities” is an umbrella term that refers to disabilities that interfere with day-to-day functioning but do not necessarily have a visible physical manifestation.37 Many participants did not receive a formal diagnosis until later in life and expressed elements of shame as perceived by their classmates’ attitudes toward their accommodations. These subthemes are both consistent with the literature on invisible disabilities, which has examined social and organizational barriers including others questioning the validity of and not understanding the full extent of individuals’ disabilities.37

When connecting the first and second themes, we see that participants feel a layer of complexity exists in navigating the disability tax with an invisible disability because they perceive society to be less understanding of and less accommodating to learning, sensory, and emotional disabilities than physical disabilities, another novel finding that has not been previously reported in physical therapist educational research.

Theme 3 showed that participants sought out both informal support from their entry-level educational programs and formal support from their university disability support services offices during the process of applying for NPTE accommodations. Some participants expressed frustration with faculty who were not well-versed in the accommodations processes, especially when some faculty provided factually incorrect information.

Physical therapist educational programs should recognize that students are looking for additional support during the NPTE application process and consider implementing a coordinated approach to assist these students, as recommended by the United States Government Accountability Office.38 Doing so may help to ease the burden of the disability tax expressed in Theme 1 and may promote improved visibility of the invisible disabilities seen with Theme 2.

Study Strengths

The mantra “Nothing About Us Without Us” is a rallying cry within the Disability Rights movement. James Charlton, a disability rights activist, expands on the above manifesto39,p17 by stating that it “forces political-economic and cultural systems to incorporate people with disabilities into the decision-making process and to recognize that the experiential knowledge of these people is pivotal in making decisions that affect their lives.” The major strength of this study is its intentional inclusion of individuals with disabilities within the narrative of applying for testing accommodations on the NPTE. Further strengths of this study include representation from multiple geographic regions and states following different accommodations applications processes as well as the recruitment of applicants with a variety of self-reported disability types (including those with multiple disabilities).

Limitations

The primary limitation of this study is its small sample size. The decision to proceed with only 5 interviewees was made, with the understanding that the sensitive nature of self-reporting one’s disability status may have deterred potential participants and thereby reduced the number of eligible subjects willing to proceed. Despite the sample size, theoretical and methodological considerations were made throughout the research process to maximize trustworthiness. Additionally, the sample size allowed the PI the opportunity for thorough exploration and detailed analysis within the research context, as well as the ability to lay the foundation for future larger-scale studies. An expansion of this work is in progress, which incorporates an examination of how attitudes toward disability impact the lived experiences of entry-level Doctor of Physical Therapy students with disabilities. This includes students’ choices on whether or not to seek accommodations throughout their professional educational journey, including on the NPTE.

Self-selection bias also may have impacted results, with respondents who perceived a more negative accommodations experience potentially being more willing to participate in the interview process. None of the participants reported having a physical disability, which particularly impacted the study results and the formation of Theme 2. It is possible that this lack of representation is consistent with physical disabilities being underrepresented in physical therapist educational programs,2 and it is also possible that by not explicitly defining disability in the survey, the study may have been biased toward recruiting those with learning, sensory, and emotional disabilities.

Insights

Upon reflection, explicitly asking about the specific accommodations that participants requested on the NPTE would have provided a clearer picture of the accommodations request process for the PI. Some participants offered this information during the interviews while others did not. Additional modifications to the interview guide for future larger-scale studies could include questions focused on further exploring the socio-environmental factors impacting applicants requesting accommodations. This would provide a deeper understanding of what these applicants face so that educational programs and licensing bodies could better support NPTE candidates.

To increase generalizability of the results, future research using similar methodology could include a larger and more robust sample of participants with broader demographics, including racial, gender, and geographic diversity as well as representation from individuals with physical disabilities.

Implications of Findings for Physical Therapist Education

Recognizing that systemic disparities are experienced by NPTE candidates seeking accommodations is the first step in addressing those disparities. Prior to progressing to action-focused solutions, we as a profession must understand the lived experiences of people with disabilities who have taken the NPTE.

Conclusion

The individual experiences of NPTE candidates in this study applying for accommodations varied based on their geographic location as well as their access to institutional, educational, financial, emotional, and temporal resources, which contribute to potential disparities experienced by candidates seeking accommodations. Despite these individual differences, through the EDQ approach, this study found consistency in three major themes that emerged when contextualizing participants’ lived experiences.

Applying for testing accommodations on the NPTE adds another layer of stress to an already highly stressful experience for most testing candidates. Improved ease of access to information related to the accommodations process and a more streamlined application approach nation-wide would mitigate some of that stress and anxiety. To truly advocate for the ideal of “Nothing About Us Without Us,” we must continue the work of fully embracing individuals with disabilities within the profession of physical therapy, including those applying for testing accessibility accommodations on the NPTE.

Appendix

Semi-Structured Interview Questions

- Tell me about your typical day as an individual with disability…

- in your work life…

- in your social life…

- in your family…

- Tell me about your experience with seeking accommodations in PT school…

-

- Tell me about how your program supported of your accessibility needs.

- Tell me about how your university was supportive of your needs.

- Tell me about your experience with seeking accommodations on the NPTE…

- Tell me about how you felt supported during the process of applying for accommodations.

- Tell me about your NPTE testing experience…

- Describe how the testing experience was the same and different from the exams you took during PT school.

- Did you take a licensure prep course? If yes, who paid for it? Describe your experience preparing for the NPTE.

- Did you take any NPTE practice exams prior to the real exam? If yes, please tell me about your experience with practice exams

- Please feel free to provide any additional details you feel are important regarding your NPTE exam experience.

References

- American Physical Therapy Association. HOD P08-22-14-18: Equitable Disability Accommodations in Physical Therapy. Published online October 26, 2022. Available at: https://www.apta.org/apta-and-you/leadership-and-governance/policies/equitable-disability-accommodations. Accessed April 15, 2023.

- Hinman MR, Peterson CA, Gibbs KA. Prevalence of physical disability and accommodation needs among students in physical therapy education programs. JPED. 2015;28(3):309-328. Available at: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1083842. Accessed April 15, 2023.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Disability and Health Data System (DHDS); 2022. Available at: http://dhds.cdc.gov. Accessed April 15, 2023.

- National Center for Education Statistics. Number and percentage distribution of students enrolled in postsecondary institutions, by level, disability status, and selected student characteristics: 2015-16. Published 2018. Available at: https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d17/tables/dt17_311.10.asp. Accessed March 7, 2023.

- French S, Swain J. The relationship between disabled people and health and welfare professionals. In: Handbook of Disability Studies. SAGE Publications; 2001:734-753. doi:10.4135/9781412976251.n33

- Van Der Klift E, Kunc N. Being Realistic Isn’t Realistic: Collected Essays On Disability, Identity, Inclusion, and Innovation. Tellwell Talent; 2019.

- McClintock M, Rauscher L. Ableism curriculum design. In: Teaching for Diversity and Social Justice: A Sourcebook. Routledge; 1997:198-230.

- VanPuymbrouck L, Friedman C, Feldner H. Explicit and implicit disability attitudes of healthcare providers. Rehabil Psychol. 2020;65(2):101-112. doi:10.1037/rep0000317

- Singh S. Clinic design standards: Accessibility considerations for caregivers. Ped Phys Ther. 2020;32(1):84-85. doi:10.1097/PEP.0000000000000668

- Smart JF. The power models of disability. J Rehabil. 2009;75(2):3-11. Available at: https://aac.matrix.msu.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/The-Power-of-Models-of-Disability.pdf. Accessed March 7, 2023.

- Williams-Whitt K. Impediments to disability accommodation. Relations Industrielles. 2007;62(3):405-432. doi:10.7202/016487ar

- Ward SR, Ingram DA, Mirone JA. Accommodations for students with disabilities in physical therapist and physical therapist assistant education programs: a pilot study. J Phys Ther Educ. 1998;12(2):16. doi:10.1097/00001416-199807000-00005

- Beckel C. Clinical education accommodations for physical therapist students with disabilities. [Doctoral dissertation]. Saint Louis, MO. Saint Louis University. 2012. https://www.proquest.com/docview/1030120202/abstract/755DA5D9B7164FCBPQ/1

- Francis NJ, Salzman A, Polomsky D, Huffman E. Accommodations for a student with a physical disability in a professional physical therapist education program. J Phys Ther Educ. 2007;21(2):60-65. doi:10.1097/00001416-200707000-00010

- Dhillon S, Solomon P. Accommodating students with disabilities in professional rehabilitation programs: an institutional ethnography informed study. J Humanit Rehabil. 2022. Published November 14, 2022. Available at: https://www.jhrehab.org/2022/11/14/accommodating-students-with-disabilities-in-professional-rehabilitation-programs-an-institutional-ethnography-informed-study/. Accessed April 15, 2023.

- Hinman MR, Peterson CA, Gibbs KA. Educating students with disabilities: are we doing enough?: J Phys Ther Educ. 2015;29(4):37-41. doi:10.1097/00001416-201529040-00006

- Ingram D, Mohr T, Mabey R. Testing accommodations: implications for physical therapy educators and students. J Phys Ther Educ. 2015;29(1):10. doi:10.1097/00001416-201529010-00004

- APTA Academy of Leadership and Innovation. Catalyst Groups. Available at: https://www.aptaali.org/general/custom.asp?page=HPACatalystGroups. Accessed June 13, 2024.

- FSBPT. Testing Accommodations. Available at: https://www.fsbpt.org/Secondary-Pages/Exam-Candidates/Testing-Accommodations. Accessed February 20, 2023.

- FSBPT. Accommodations Guidelines. Available at: https://www.fsbpt.org/portals/0/documents/exam-candidates/AccommodationsGuidelines.pdf. Accessed February 20, 2023.

- FSBPT. Accommodations Request Form. Available at: https://www.fsbpt.org/portals/0/documents/exam candidates/AccommodationsRequestForm.pdf. Accessed February 20, 2023.

- FSBPT. Accommodations Appeal Form. Available at: https://www.fsbpt.org/portals/0/documents/exam-candidates/AccommodationsAppealForm.pdf. Accessed February 20, 2023.

- Physical Therapy Board of California. Disability Accommodation Request for Examination. Accessed June 8, 2023.

- Physical Therapy Board of California. Available at: https://www.ptbc.ca.gov/. Accessed June 8, 2023.

- Physical Therapy Board of California. Forms. Available at: https://www.ptbc.ca.gov/forms/index.shtml. Accessed June 8, 2023.

- Connecticut State Department of Public Health. Physical Therapist Licensure. Available at: https://portal.ct.gov/DPH/Practitioner-Licensing–Investigations/Physicaltherapist/Physical-Therapist-Licensure. Accessed June 8, 2023.

- Stebbins R. Exploratory research in the social sciences. SAGE Publications; 2001. doi:10.4135/9781412984249

- Sandelowski M. Whatever happened to qualitative description? Res Nurs Health. 2000;23(4):334-340. doi:10.1002/1098-240x(200008)23:4<334::aid-nur9>3.0.co;2-g

- Sandelowski M. What’s in a name? Qualitative description revisited. Res Nurs Health. 2010;33(1):77-84. doi:10.1002/nur.20362

- Hunter DJ, McCallum J, Howes D. Defining Exploratory-Descriptive Qualitative (EDQ) research and considering its application to healthcare. GSTF J Nurs Health Care. 2019;4(1). https://eprints.gla.ac.uk/180272/

- Doyle L, McCabe C, Keogh B, Brady A, McCann M. An overview of the qualitative descriptive design within nursing research. J Res Nurs. 2020;25(5):443-455. doi:10.1177/1744987119880234

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77-101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- OToole C. Disclosing our relationships to disabilities: an invitation for disability studies scholars. Disabil Stud Q. 2013;33(2). doi:10.18061/dsq.v33i2.3708.

- Munhall PL. Nursing Research: A Qualitative Perspective. 5th ed. Jones & Bartlett; 2012.

- Lincoln YS, Guba EG. Establishing trustworthiness. In: Naturalistic Inquiry. SAGE; 1985:289-331.

- Olsen SH, Cork SJ, Anders P, Padron R, Peterson A, Strausser A, Jaeger PT. The disability tax and the accessibility tax: the extra intellectual, emotional, and technological labor and financial expenditures required of disabled people in a world gone wrong…and mostly online. Incl Disabil. 2022;(1):51-86. Available at: https://ojs.scholarsportal.info/ontariotechu/index.php/id/ article/view/170/78. Accessed April 15, 2023.

- Mullins L, Preyde M. The lived experience of students with an invisible disability at a Canadian university. Disabil Soc. 2013;28(2):147-160. doi:10.1080/09687599.2012.752127

- US Government Accountability Office. Higher Education and Disability: Improved Federal Enforcement Needed to Better Protect Sudents’ Rights to Testing Accommodations. 2011:1-44. Available at: https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-12-40. Accessed April 15, 2023.

- Charlton JI. Nothing About Us Without Us: Disability Oppression and Empowerment. Univ. of California Press; 2000.

Member since 2019 | JM14274

Member since 2019 | JM14274

NO COMMENT