Utilizing Drama to Teach Intervention Strategies for Patients With Alzheimer’s Disease: The Intersection of Humanities and Clinical Science

By Stephen Carp, PT, PhD; Rebecca Stein R.T.(R)(MR)(ARRT);

Kathleen Ehrhardt MMS, PA-C, DFAAPA; Susana L. Keller, CScD, CCC-SLP

Introduction

Over the past 20 years, interprofessional education (IPE),1 clinical simulation (CS),2 standardized patients (SPs),3 and humanities education4 have markedly altered the pedagogical landscape of healthcare higher education. The rationale for introducing these novel pedagogies was the World Health Organization’s advocating for interdisciplinary and collaborative healthcare education to improve health outcomes.5 The Interprofessional Education Collaborative (IPEC), a non-profit organization, was established in 2009 to improve and facilitate IPE. The mission of IPEC is to ensure that new and current health professionals are proficient in the competencies essential for patient-centered, community- and population-oriented, interprofessional, collaborative practice.6

The Power of Clinical Simulation

An effective facilitator of IPE in entry-level healthcare student education is clinical simulation. Medical CS replicates real-world healthcare scenarios in an educational or healthcare environment, typically on campus, that is safe for education and experimentation purposes. Clinical simulation involves the manipulation of tools, devices, and environments to mimic a particular aspect of clinical care. Within the broad heading of CS are several specific learning methods, which include standardized patients, virtual reality, computerized simulation, high-fidelity manikins, tissue simulators, and task simulators.7

In the final decades of the 20th century, entry-level healthcare education, due to the advancing complexity of clinical practice, focused curricula toward medical content at the expense of humanities education. Recent evidence suggests that the re-inclusion of health humanities content into entry-level healthcare curricula has the capacity to deepen the understanding of and care for the patient.8 Health humanities content can also provide a unique space to question, analyze, and critique contemporary practice, encourage self-reflection, enhance clinical mental and physical well-being, avoid clinical burnout, and improve personal resiliency.9,10 Current health humanities scholarship draws from fields of philosophy, bioethics, history, law, and anthropology, as well as the arts (literature/narrative, poetry, music, film studies, and visual arts).11 The unifying theme of this content is to foster a greater understanding of the human condition.11

Defining Drama in Education

The use of dramatic arts in entry-level healthcare education is not new but is hampered by a lack of a standard definition of drama in education. Role plays and simulations are commonly used in entry-level healthcare education, without the roots from drama or theater mentioned or acknowledged.12 These are typically role-playing activities involving students where one student is cast as the caregiver and the other the patient or a member of the patient’s family. Role play and simulations without the artistic underpinnings are often performed for skill training, and are “to drama as diagrams are to visual art.”13

Role playing and simulations have benefits in entry-level healthcare education but should be considered as educational activities and not dramatic arts. Drama, as summarized in Jefferies et al14 in their systematic review of drama in nursing healthcare curricula, discussed several ways drama can support student learning and professional development. Drama was found to enhance nursing students’ understanding of patient experience through the development of empathy skills. Empathy in healthcare has been defined as the process where a health worker develops an understanding of a patient’s world by the formation of cognitive and emotional connections with them.15 These results are supported by two additional studies.16,17

Bolton wrote that to be labeled “drama” requires artistic underpinnings since drama is an art form.13 The dramatic context is crucial, and drama includes content, theme, substance, emotion, subject matter, and curriculum.14 The art of drama is used to illuminate the truth about an experience or opportunity and not just for retrieving facts or practicing skills. The existence of drama as an art form depends on the participants’ engagement in both the real and fictional contexts at the same time. This dual imagery, viewing the situation from two perspectives simultaneously, is called “metaxis” and adds an important reflective dimension.18

Affective Domain Teaching

Preparing entry-level healthcare students to develop appropriate, professional, and effective personal relationships with patients with Alzheimer’s disease and their families has been problematic.19-22 Research has shown that this content is typically taught in entry-level healthcare programs via lecture (cognitive domain). Empirically, this content would seem to lend itself to presentations in the affective domain. Examples of affective domain teaching include the use of the think-pair-share technique, reflective journaling, simulation and role play, motivational interviewing, and structured controversy.23 Practicality and technology are often cited as confounding variables to this approach.23,24 Confounding variable examples include a belief that affective domain teaching preparation is more time-consuming than cognitive domain teaching preparation, a belief that students prefer being “spoon-fed” content rather than learning in a collaborative classroom, and the challenge incurred transferring classroom affective teaching modules to online learning.24

Methods

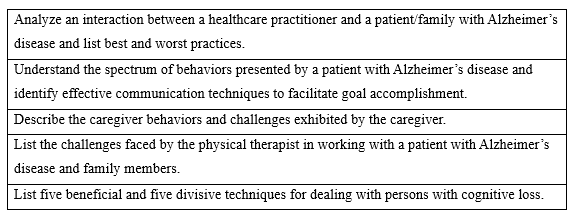

Since participation in this research was a curricular requirement of entry-level speech and language pathology (SLP), physician assistant (PA), and physical therapy (PT) students, the sampling was purposive and all-inclusive. Learner objectives were developed and are listed in Table 1.

Table 1. Learner Objectives

This qualitative research aims to determine if IPE combined with CS using SPs in a dramatic presentation facilitates learning of professional and effective personal interactions with patients with Alzheimer’s disease and their families.

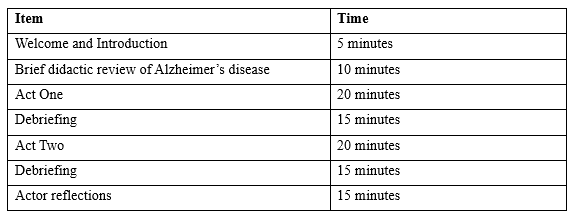

The agenda for the dramatic presentation is described in Table 2. Although all three cohorts attending the presentation had previously received cognitive-based content on Alzheimer’s disease, the consensus was that the students would benefit from a short review of the subject before the dramatization. The play was written as a two-act drama—each act with the same roles and themes. However, Act One presents an unsuccessful outcome due primarily to the physical therapist presenting confounding variables related to his verbiage, actions, and interventions. Following Act One, there was an audience debriefing with questions developed by a long-practicing qualitative researcher.

Act Two presents a successful outcome primarily due to the effective behaviors and verbiage utilized by the physical therapist. Act Two was also followed by debriefing utilizing the same questions employed after Act One. The three actors were then brought back to the stage to each describe their reflections on playing the husband, patient, and physical therapist. The attending students were required to submit anonymous reflections through the University’s student management system within 24 hours of the presentation.

Table 2: Presentation Agenda

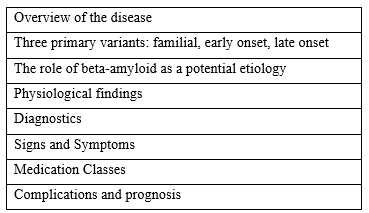

The 20-minute evidence-based didactic presentation about Alzheimer’s disease was produced by the research team. The presentation was given to the students just before the two-act play. Key topics of the presentation given to the students before the dramatic presentation are listed in Table 3.

Table 3: Key Topics of the Didactic Presentation on Alzheimer’s Disease

A two-act, three-person play was written by the researchers. The three actors were members of the University’s Standardized Patient Registry, and all had extensive experience on stage, screen, and television as actors. Stage choreography was developed by members of the University Drama Department. Rehearsals were held over three weeks. Both acts had the same three characters. The play is titled: Stolen Memories: An Alzheimer’s Story In A Two-Act Play. Below are the fictional biographies of the three characters in the play. The title was developed as a “play” on the characters’ last name.

Jasmine Story

Jasmine Story is a 61-year-old woman diagnosed two years ago with age-related Alzheimer’s disease. Following her most recent neurologist visit, her Alzheimer’s status was degraded from early (mild) to middle (moderate) stage. She is a retired second-grade teacher. She received her bachelor’s degree from Morehead State University in Kentucky and her master’s degree in education from the University of Pennsylvania. She retired from teaching at age 60 due to the progression of her disease. She is now receiving Social Security disability.

Jasmine resides with her husband Charles in a two-story home with the master bath on the second floor and a powder room on the first floor. She walks independently at home, holding onto furniture. She has begun falling about once per week. Charles has placed a gate at the top and bottom of the steps because he is afraid of Jasmine falling on the steps.

Jasmine can no longer perform household chores such as washing, drying, and folding clothes unless Charles is assisting. She can brush her teeth and wash her face if Charles provides verbal cueing and set-up. She is on a toileting schedule, but frequent accidents have led to the need to wear a pull-up diaper “just in case.” Jasmine can feed herself but prefers “finger foods.” Charles does not trust her to use the stove or oven.

Jasmine likes holding Charles’ hand and often does not make eye contact with others. At home, she likes to watch television, especially television programs from her youth such as Full House. With strangers she tends to become somewhat paranoid, timid, and fearful. She talks often with Charles but withdraws around strangers. Last week, Jasmine’s daughter Sheila was not sure that her mother recognized her.

Jasmine has been referred to outpatient physical therapy due to a recent fall resulting in a stage II sprain of her left knee medial collateral ligament (MCL), the large ligament on the inside of the left knee. There wasn’t a fracture, but the knee is swollen and painful—especially when standing and walking. MCL sprains typically take six weeks or more to completely resolve. No cast is needed; the usual treatment is a compressive wrap and encouraging ambulation and range-of-motion exercises of the knee. In very painful cases, a removable brace called a knee immobilizer may be used.

Dr. Whitenack, the Story’s family physician, recommended physical therapy for Jasmine to enhance her function and safety at home. The goal of this physical therapy session is to teach Jasmine how to use a walker (she cannot currently walk without it due to pain) and to teach knee exercises to avoid a flexion contracture and permanent weakness.

Charles Story

Charles Story is a 61-year-old accountant working in the Financial Department at a local university. He was hoping to work until 66 years of age but is very concerned that he will need to stop working to become a full-time caregiver for his wife.

Charles’s supervisor has been very accommodating with Charles and his issues with Jasmine. He has permitted him to work from home Monday, Wednesday, and Friday, but requires Charles to be on campus Tuesday and Thursday. Charles and Jasmine have one daughter, Sheila, who is married with three children, ages 2, 4, and 5. Sheila visits every Tuesday and Thursday to check on her mom when Charles is at work.

Charles is becoming frustrated that the quality of his work from home is affected by his need to care for Jasmine. Due to Sheila’s schedule, Jasmine is home alone for about three hours each Tuesday and Thursday afternoon. Three days ago, on a Tuesday, when Charles returned home from work, he found Jasmine on the floor. She had fallen and sprained her knee. Charles took her to the hospital; the sprain was diagnosed as the aforementioned knee injury, and physical therapy was ordered.

Charles is very concerned about finances. The Storys have about 6 months of cash in the bank but if Charles is forced to quit working, there will be no income and no medical insurance. Five years are remaining on their house mortgage at $1400/month, and a car payment is due monthly. Charles has a 401K, but without a pension, he will need this money for retirement income.

Charles is hoping that physical therapy is successful at teaching Jasmine to walk and prevent further falls. He is currently challenged to get her to the bathroom, and he has been carrying her up the steps to bed. His back is sore.

Chris Smith

Chris is the physical therapist assigned to care for Jasmine. In the first case scenario presented, Chris is overworked and challenged by his productivity standard. He is required to treat 13 patients per day and is constantly looking at his watch. He tends to be “all business.” Rather than developing a professional relationship with his patients he tends to focus on the physical therapy tasks, often not listening to his patient’s concerns. He is challenged by deductive thinking; he focuses on a “knee” or “hip” and often ignores other corporal systems and the patient’s verbalized needs and goals. He is a bit scattered and often forgets his patients’ names and diagnoses due to his perceived level of being busy. He is a typically overworked clinician. He is very concerned about professional burnout.

In the second case scenario, Chris is an exemplary physical therapist. He is very empathetic and patient-focused. He can successfully discern the intricacies of his patient and patient’s family beyond her knee injury. He can understand Charles’ low back pain, his caregiver needs, and his exhaustion. He senses Jasmine’s anxiety and addresses it. He uses touch appropriately and always explains what his actions are before he performs them.

The Dramatic Presentation

Act One Excerpts: The Poorly Interactive Physical Therapist

Chris: My name is Chris Smith, and I will be your therapist. (He reaches out and shakes Charles’ hand. He reaches his hand to Jasmine but she looks at Chris warily. She does not lift her hand. Chris reaches down and takes Jasmine’s hand in his. She pulls back quickly. She looks at Chris quizzically. She becomes frightened.)

Jasmine: Charles, who is this man? Why did he try to touch me! I want to go home. I don’t like this place. I don’t like strangers touching me!

Chris: (Defensively) I’m just trying to shake your hand. No harm no foul. (Chris is still towering over Jasmine.)

Jasmine: Huh. I don’t understand. (Charles senses Jasmine’s unease and puts his arm around her shoulder. She smiles warmly at him. She turns back to Chris and is once again anxious.) Charles, let’s go home. I want to go home. Take me home. I want to watch television!

Chris: (ignoring Jasmine’s anxiety) So how do you wish to be addressed? Jasmine or Mrs. Story or something else?

Jasmine: (to Charles) What does he mean? He wants my name? Who is this man?

Charles: (to Chris) Please call her Jasmine.

Chris: Okay, Jasmine. According to our medical record, you apparently fell two nights ago and injured your knee. You went to the emergency department, which indicated you had a grade II sprain of the left medial collateral ligament. Is that true?

Jasmine: Who is this man, Charles? I am scared. What is he talking about. Grade two…..

Charles: (to Chris) I am unsure if you know this but I am sure it is in her records. Jasmine was diagnosed with dementia two years ago. I am her caregiver with help from our daughter.

Chris: (frustrated and looking at his watch) Yes, I know. I know. I read this in the chart. We need to speed things up. I have another patient in 30 minutes. (Turns to Charles.) Rather than trying to get information from Jasmine, I’ll talk to you instead. She seems a bit confused. Is that what happened with your sister? Was there a fall?

Charles (a little aggravated) She is my wife. She is not my sister. (To Jasmine) The man wants to know your medical history. (Slowly and caringly) You had your appendix taken out, didn’t you, Jazzy?

Jasmine: (relaxing as she stares at Charles) Yes. I was eight years old. My mommy stayed in the hospital with me.

Charles: And you take medicine for your blood pressure?

Jasmine: Blood pressure. That is Dr. Whitenack, isn’t it? He takes care of my blood pressure. He is a very nice man. (turning to Chris) He never hurts me.

Charles: (hugs Jasmine). That is correct. He never hurts you. You are one smart lady (he beams, and she smiles back).

Chris: (impatiently) Let me start by taking your blood pressure. (He stands and places the cuff around Jasmine’s arm and begins inflation. She initially looks at the cuff quizzically but as the pressure increases, she begins to get anxious.)

Jasmine: Take it off!! You are hurting me!! Take it off? Charles, make him take it off!

Chris: You must be patient. I need to do this. You need to control yourself.

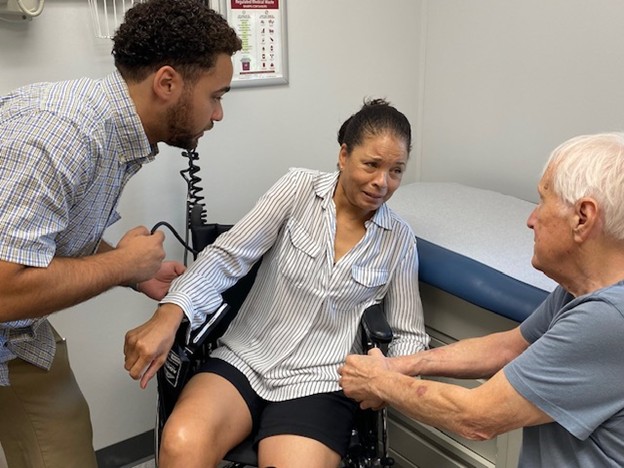

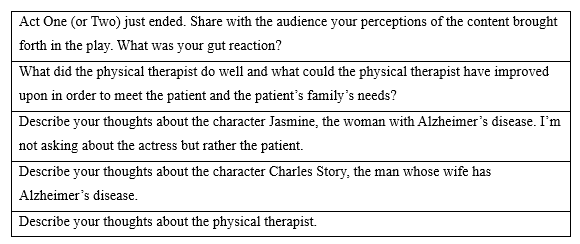

Figure 1: Mr. and Mrs. Story in the Physical Therapy Waiting Room. Mrs. Story is unsure where she is and why she is there. She reaches out to her husband, the only constant in the experience.

Figure 2: A Rushed Physical Therapist Attempting to Take Mrs. Story’s Blood Pressure. Figure 2 depicts a very frightened Mrs. Story. She does not know where she is and who this man is who is grabbing her arm. She shouts for her husband to take her home.

Act Two Excerpts: The Empathetic Physical Therapist

Chris: (quietly to Charles) From the way you are moving it looks like you have low back pain. I’ll talk to you about that later. (Chris leans forward to talk with Jasmine.) Hello! What a pretty blouse you have. My wife has the same one. It really matches your eyes. (He pauses and waits for Jasmine to smile). Would you like to see a picture of my wife and child?

Jasmine (tentatively) Yes…

Chris: (takes out his phone and finds a picture) My wife’s name is Annie. I have one daughter. Her name is Matilda and she is two years old. Aren’t they beautiful? Annie is a teacher.

Jasmine: (studies the screen) Beautiful. Beautiful baby. (She fingers the screen as if she is touching the baby’s skin.) Is that Sheila?

Chris: (to Charles) Sheila?

Charles: No that is Matilda, Chris’ baby. (To Chris) Sheila is our daughter’s name. She is a bit older than Matilda. (To Jasmine) You really loved that baby stage, didn’t you, Jaz? (Jasmine smiles). You love children.

Chris: My wife is a teacher.

Jasmine: Teacher?? Teacher?? (Excitedly) Charles, I am a teacher.

Charles: Yes. You are a teacher. A terrific teacher. Once a teacher always a teacher, Jazzy. (To Chris) Jazzy taught for 35 years in the Philadelphia Public Schools system. Mostly second grade. Her Master’s is from Penn.

Chris: (to Jasmine). My wife teaches second grade!! She said that is the best grade to teach.

Jasmine: (repeats Chris’s comment) Second- grade- is- the- best- grade- to- teach.

Chris: (to Jasmine, smiling) The best grade to teach. (Jasmine smiles at him and gently touches his face. She again looks at the picture on the phone.)

Jasmine: You have a beautiful daughter. (She hands back the phone.)

Chris: I am a very lucky man. And your husband is very lucky to have you.

Jasmine: (not fully understanding but repeats) Yes Charles- is very- lucky- to- have- me.

Chris: (Reaches for the table and picks up a knee brace.) Jasmine, do you know what this is? (He hands the brace to Jasmine to examine.)

Jasmine: A brace. My mommy wore one on her knee.

Chris: (Excitedly, and fist bumps Jasmine.) You are 100% right. This brace will help control your knee pain. I’d like you to wear it when you are walking. Just like your mom did. Is that okay?

Jasmine: (warily) Well, yes. Like my mom did.

Charles: I’ll see to it.

Chris: (to Charles) And she needn’t wear it while showering, sitting for long periods, or in bed. The sole purpose is to decrease her pain to permit her to walk better than she has been. (To Jasmine) May I put the brace on your leg? Again, if I hurt you, tell me to stop. You are the boss.

Jasmine: (confidently) I am the boss!!

Chris: (Chris rewraps the knee and places the brace on Jasmine’s leg.) (To Jasmine) Your knee problem is only a temporary inconvenience. It will all be better in a few weeks, and you will be as good as new. Do you know what a temporary inconvenience is?

Jasmine: (thinks) …Poison ivy is a temporary inconvenience.

Results

The qualitative data from this study originated in the debriefing and through the written reflections anonymously submitted by the students.

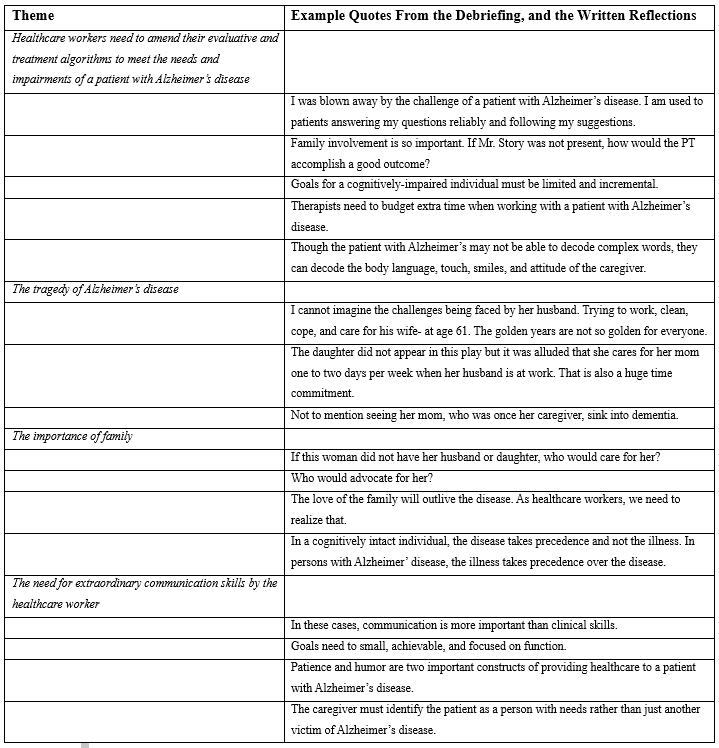

Table 4 lists the debriefing questions offered after Act One and after Act Two. The questions were formulated by an experienced qualitative researcher. Data were analyzed through thematic analyses. Thematic analysis identifies, categorizes, analyzes and interprets patterns written or spoken narratives.

Table 5 lists the five themes identified by the researchers, and examples of each from the debriefing and written reflections.

Table 4: Debriefing Questions

Table 5: Identified Themes and Examples of Each

Evaluation of Student Comments

The healthcare students’ comments centered on five themes. The most referenced theme was Healthcare workers need to amend their evaluative and treatment algorithms to meet the needs and impairments of a patient with Alzheimer’s disease. Nearly 40% of student comments referenced this theme. Entry-level students develop conceptual frameworks or algorithms related to evaluative and intervention processes. One student shared:

“I have a recipe in my head how to evaluate and treat soft tissue injuries of the knees. A to B to C to D. I can now see that this does not work with this cohort. I need to use my words, body language, smile, and tone to develop a bond with the patient.”

And another:

“When I provide education, I will need to teach the patient and the family.”

Another:

“With this group I need to take it off autopilot.”

Lastly:

“A small gain is still gain.”

Students realized that treating patients with Alzheimer’s is an art unto itself—requiring different skills than treating patients who are cognitively intact.

The second theme, The tragedy of Alzheimer’s disease, emphasized the learning by students of the scope and breadth of this disease; and how its impacts across boundaries such as human relationships, finances, time, physical effort, and planning. One student wrote:

“This is not like a rotator cuff injury in a 20-something.”

The third theme identified was The need for extraordinary communication skills by the healthcare worker. Students described the need, in this cohort, to employ “top of the license” (as one student wrote) communication skills. Another student wrote:

“In a weird way, perhaps the best parallel would be working in a hospice. In both (sic) patients on hospice and with Alzheimer’s disease, the future is clear but we just do not know where or when. Words become more important than deeds.”

The fourth theme identified was The importance of family. Students spoke and wrote eloquently of how wonderfully the husband cared for his wife. One student called him a “role model.” Another student shared in a reflection:

“I guess it is true. When all else is gone, all that is left is love.”

Discussion

As healthcare workers, we are taught the difference between diagnosis and illness. The diagnosis informs us of the pathology: cellular unit dysfunction, metabolic abnormalities, diagnostics, and intervention. Illness is related to the impact of the diagnosis on the patient and the patient’s support system. An effective bridge for the healthcare worker to move from diagnosis to illness is empathy: empathy toward the patient, toward the family and even toward the members of the healthcare team struggling to treat the patient. At the metacognition level of teaching entry-level healthcare students, humanities education and particularly the dramatic arts can add an incredible amount of understanding, appreciation, and empathy to student content knowledge.

This is especially important when, as students or as licensed workers, we are asked to work with patients and families with complex disease processes. Dramatic Arts, as perhaps a prototypical example of humanities content, is an important and underused adjuvant teaching pedagogy. When used correctly in entry-level healthcare programs, this tool stimulates the learner’s creativity and problem solving. It can challenge students’ perceptions about their world, their biases, and about themselves.

The use of Dramatic Arts permits reflection-in-action and reflection-on-action. How many times have we exited a dramatic production only to relive specific aspects of the play or movie days, weeks, or months later? In addition, university educators are trained to primarily teach in the cognitive domain; actors are trained to teach in the affective domain.

Dramatic Arts in Curricula

Dramatic Arts can be inserted into entry-level curricula in several ways. The authors of this manuscript chose to write a play because we enjoy writing, and we were able to assemble the script content in such a way as to match our learning objectives. Our University is fortunate to have a healthcare simulation program with many qualified standardized patients to call upon as actors. However, the insertion of the Dramatic Arts need not be as complex as our process. Less complex methods may include live poetry and play readings using students, watch-parties for films and recordings of theater, and attendance as a class at community theater productions.

One colleague, a pathophysiology teacher, requires her students to write a one-act play, involving a family member with a specific diagnosis. The play must depict the interaction of an occupational therapist teaching the patient and family about the diagnosis. My colleague found that requiring the students to write the dialogue has become an effective learning tool about the diagnosis but also about developing the therapist-patient cooperative alliance. She also uses the assignment to teach about implicit bias that can appear in the narrative.

Drama in Healthcare Education

Drama, when employed in healthcare education, can educate students using the four teaching domains: spiritual, cognitive, affective and psychomotor. Therefore, the chance of meeting the needs of varied learner types is advanced. Dramatic exploration can provide students with an outlet for emotions, thoughts, and dreams that they might not otherwise have the means to experience, verbalize, or write. When drama includes a medical diagnosis, such as ours with Alzheimer’s disease, the learner, through empathetic bonding, can become each character—the patient, the therapist, and the spouse—and develop an appreciation of the struggles, concerns, needs, and pain of each character far beyond what can be perceived when learning in the cognitive domain.25 What an amazing learning experience!

Drama happens in a safe arena, where actions and consequences can be examined, discussed, and in a very real sense, experienced, without the dangers and pitfalls that such experimentation would obviously lead to in the “real” world.26 Drama is real life with the dull parts removed. Including an interprofessional component such as adding more than one healthcare student professional cohort to the audience and debriefing session, adds richness to the learning and to the reflective process.

A Call for New Research and Curricular Design

Although there are limitations to our study—only one data collection site, only three disciplines involved, and a lack of quantitative outcome data—we feel that our research validates the effectiveness of this novel pedagogy. We hope it will incur interest in health educators to include this educational tool in entry-level healthcare education, and to consider producing rigorous research related to the effectiveness of the use of Dramatic Arts in entry-level student education. Healthcare educators should cogently consider the addition of Dramatic Arts to curricular design.

References

- Guraya SY, Barr H. The effectiveness of interprofessional education in healthcare: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2018;34(3):160-165.

- Lamé G, Dixon-Woods M. Using clinical simulation to study how to improve quality and safety in healthcare. BMJ Sim Tech Learn. 2020;6(2):87.

- Herge EA, Lorch A, DeAngelis T, Vause-Earland T, Mollo K, Zapletal A. The standardized patient encounter: a dynamic educational approach to enhance students’ clinical healthcare skills. J Allied Health. 2013;42(4):229-235.

- Blanton S, Greenfield BH, Jensen GM, Swisher LL, Kirsch NR, Davis C, Purtilo R. Can reading Tolstoy make us better physical therapists? The role of the health humanities in physical therapy. Phys Ther. 2020;100(6):885-889.

- Yan J, Gilbert JH, Hoffman SJ. World Health Organization study group on interprofessional education and collaborative practice. Journal of interprofessional care. 2007 Dec;21(6):588-9.

- Collaborative IE. IPEC core competencies for interprofessional collaborative practice: Version 3. Interprofessional Education Collaborative. 2023.

- Jones F, Passos-Neto CE, Braghiroli OF. Simulation in medical education: brief history and methodology. Princip Pract Clin Res. 2015;Sep16:1(2).

- Hafferty FW, O’Donnell JF, editors. The Hidden Curriculum in Health Professional Education. Dartmouth College Press; 2015.

- Jones T, Blackie M, Garden R, Wear D. The almost right word: the move from medical to health humanities. Acad Med. 2017;92:932–5. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.00000000000015.

- Dhara A, Fraser S. Five ways to get a grip on teaching advocacy in medical education: the health humanities as a novel approach. Can Med Educ J. 2024;15(1):75-7.

- Moniz T, Golafshani M, Gaspar CM, Adams NE, Haidet P, Sukhera J, Volpe RL, De Boer C, Lingard L. How are the arts and humanities used in medical education? Results of a scoping review. Acad Med. 2021;96(8):1213-22.

- Gelis A, Cervello S, Rey R, Llorca G, Lambert P, Franck N, Dupeyron A, Delpont M, Rolland B. Peer role-play for training communication skills in medical students: a systematic review. Simulat Health. 2020;15(2):106-11.

- Bolton C. Assessment in the drama classroom: a culturally responsive and student-centered approach. (Book review.) Educ North. 2024.

- Jefferies D, Glew P, Karhani Z, McNally S, Ramjan LM. The educational benefits of drama in nursing education: a critical literature review. Nurse Educ Today. 2021;98:104669.

- Dickinson T, Mawdsley DL, Hanlon-Smith C. Using drama to teach interpersonal skills. Ment Health Pract. 2016;19(8).

- de Carvalho Filho MA, Ledubino A, Frutuoso L, da Silva Wanderlei J, Jaarsma D, Helmich E, Strazzacappa M. Medical education empowered by theater (MEET). Acad Med. 2020;95(8):1191-200.

- Matharu KS, Howell J, Fitzgerald F. Drama and empathy in medical education. Lit Comp. 2011;8(7):443-54.

- Wells T, Sandretto S, Tilson J. Metaxis moments prompted by authentic questions in primary classroom contexts. J Applied Theatre Perform. 2023;28(2):195-209.

- Tatulian SA. Challenges and hopes for Alzheimer’s disease. Drug Disc Today. 2022;27(4):1027-43.

- Torrence C, Bhanu A, Bertrand J, Dye C, Truong K, Madathil KC. Preparing future health care workers for interactions with people with dementia: a mixed methods study. Gerontol Geriatr Educ. 2023;44(2):223-42.

- Sideman AB, Alagappan C, de Jesus AH, Ma M, Dohan D, Rosen HJ, Chodos AH, Possin KL, Borson S, Rankin KP. Challenges and approaches when addressing dementia in the context of chronic comorbid conditions in primary care settings. Alzh Dement. 2023;19:e065962.

- Bernstein Sideman A, Al-Rousan T, Tsoy E, Piña Escudero SD, Pintado-Caipa M, Kanjanapong S, et al. Facilitators and barriers to dementia assessment and diagnosis: perspectives from dementia experts within a global health context. Front Neurol. 2022;13:769360.

- Donlan P. Developing affective domain learning in health professions education. J Allied Health. 2018;47(4):289-95.

- Casey A, Fernandez-Rio J. Cooperative learning and the affective domain. J Phys Educ, Rec, Dance. 2019;90(3):12-7.

- Reeves AL, Nyatanga B, Neilson SJ. Transforming empathy to empathetic practice amongst nursing and drama students. J App Theatre Perform. 2021;26(2):358-75.

Member since 2019 | JM14274

Member since 2019 | JM14274

NO COMMENT