Art, Well-being and Medicine at the Barnes Foundation

By William M. Perthes, Bernard C. Watson Director Adult Education, The Barnes Foundation

The Intersection of Science, Medicine, and Art

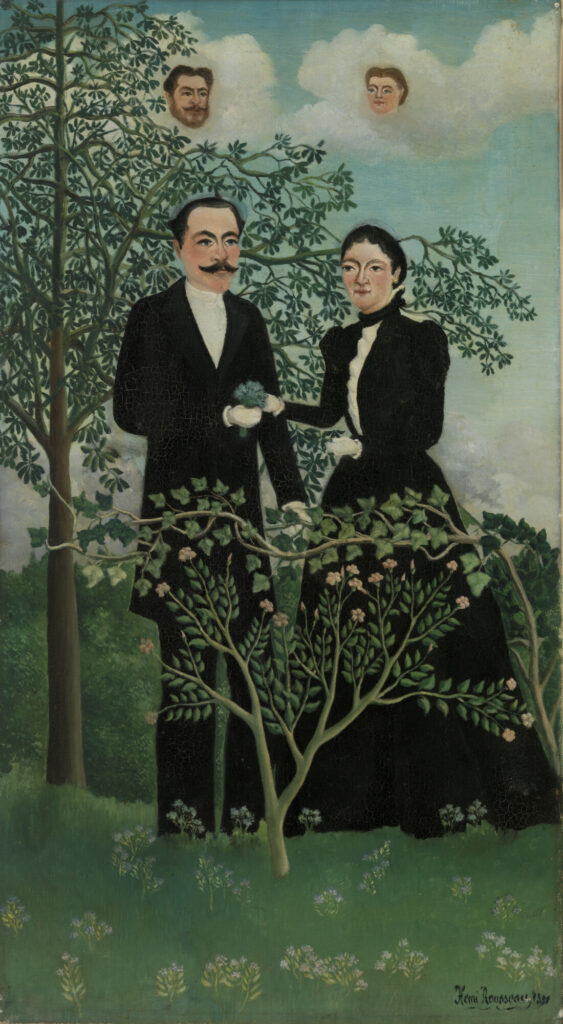

On a recent Wednesday afternoon, a pair of first-year students from the Philadelphia College of Osteopathic Medicine stood in front of one of Henri Rousseau’s dreamlike, allegorical portrait paintings in gallery 19 at the Barnes Foundation. Provided with a detailed exercise sheet, and working independently, they had been instructed to take 10 minutes to consider: “Who are these people? What are they doing? What is their relationship to each other?” They were also asked to be aware of: “What aspects of the picture led you to draw your conclusions? What in the painting supported those conclusions? And with what level of confidence?” Finally, they were asked to consider: “To what degree are your conclusions influenced by inferences or interpretations that went beyond what you could concretely verify in the painting itself?”

Figure 1: Henri Rousseau (French, 1844 – 1910), The Past and the Present, or Philosophical Thought (Le Passé et le présent, ou Pensée philosophique), 1899, oil on canvas, The Barnes Foundation, BF582

The students were then asked to take another 10 minutes to consider the image from an alternative point of view: “What other conclusions might be drawn from the same image? What else might be happening? How else might you explain what you see?” and “What would you say?” Partners then discussed their interpretations with each other, taking note where their conclusions were similar and where they differed.

Elsewhere in the collection their fellow classmates were considering the same questions with other pictures. Finally, the full group of 20 students gathered in a classroom where pairs reported on their experience, explaining to their classmates what they thought and why. After an animated conversation, the session concluded with each participant writing about their experience in a journal, reflecting on the exercise and the conversation that followed.

Why were medical students spending two hours in the middle of the school week looking and discussing works of art? They were participating in the Barnes Foundation’s Art, Well-Being and Medicine program, which uses the collection to explore topics and concepts relevant to medical education, clinical practice, and overall well-being. For instance, how might close looking at a painting help hone diagnostic skills? Or can discussing a work of art with a partner as well as a larger group enhance effective communication?

The fact that this program was taking place at the Barnes Foundation was no mere coincidence; the intersection of science, medicine and art is central to our institutional history. Following is a brief account of our founder’s path to the creation of the Barnes Method of art interpretation.

Albert C. Barnes: Education as a Path From Poverty

Albert Combs Barnes was born in 1872 to a family of modest means in the highly-industrialized Kensington section of Philadelphia. His father, John Barnes, had sustained a debilitating injury fighting in the Civil War. Early in Albert’s childhood, his father’s inability to hold steady employment forced the family to move from Kensington to a particularly rough section of South Philadelphia known as “The Neck.” Despite these trying circumstances, young Barnes excelled at school and was accepted to Central High School, which had a national reputation and was empowered to give advanced degrees. Having earned a Bachelor of Arts degree, Barnes matriculated to the University of Pennsylvania, where he graduated with a medical degree in 1892 at the age of 20. Education provided a pathway for young Barnes to move from poverty into the medical profession.

Rather than practice medicine, Barnes worked as an advertising and sales manager for the pharmaceutical firm H.K. Mulford and Company, spending extended time in Europe. While there, Barnes and his business partner Herman Hille developed a silver-based antiseptic compound designed to treat eye inflammation, especially in infants, which they named Argyrol. Barnes and Hille formed a partnership for the manufacturing of Argyrol and soon moved production to Philadelphia. They dissolved their partnership in 1908, and Barnes established the A. C. Barnes Company, taking over sole production of the product. Under his guidance, Argyrol became widely administered—making Barnes a wealthy man.

With this wealth, Barnes began collecting art. In 1912, he convinced his friend and fellow Central High classmate William Glackens—by then one of America’s most respected avant-garde painters—to go to Europe with a line of credit. The mandate was to purchase the best examples of modern paintings he could acquire. Glackens returned with more than 30 works of art, including paintings by Pierre-August Renoir, Paul Cezanne, Camille Pissarro, Vincent van Gogh, and Pablo Picasso.1 Many works from the Glackens acquisition remain in the Barnes today, forming the foundation of one of the country’s most important collections of early modern art.

Figure 2: Vincent van Gogh (Dutch, 1853 – 1890), The Postman (Joseph-Étienne Roulin), 1889, oil on canvas, The Barnes Foundation, BF37

Figure 3: Camille Pissarro (French, 1830 – 1903), Garden in Full Sunlight (Le Jardin au grand soleil, Pontoise), 1876, oil on canvas, The Barnes Foundation, BF324

A Commitment to Education

For a male, white, upper-middle-class business owner at the turn of the 20th Century, Barnes was both socially progressive and steadfastly committed to the personal and professional power of education. In his West Philadelphia Argyrol laboratory, he hired African American men to work the laboratory floor and white women as office administrators. Barnes organized the business as a cooperative, encouraging personal growth and a spirit of mutual respect among his employees. Recognizing that the amount of product needed to satisfy sales could be produced in less than eight hours, he began to set two hours of the paid workday aside for his staff to meet as a group. They read and discussed works of literature, history, and philosophy—and looked at and discussed the modern art he was collecting and hanging in the Argyrol laboratory.

One of the texts discussed in these laboratory seminars was John Dewey’s How We Think published in 1910. Impressed by Dewey’s philosophy of pragmatism and deep commitment to democratic means, in Fall 1917, Barnes enrolled in a post-graduate philosophy seminar taught by Dewey at Columbia University. Despite their dramatically-different personalities, Barnes and Dewey became close friends and confidants, remaining so for more than three decades.2

Inspired by Dewey’s philosophy of experiential education, Barnes resolved to formalize the educational experiment begun in the Argyrol laboratory. In 1922, Barnes chartered the Barnes Foundation with the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania as an educational institution dedicated to promoting the appreciation of fine art and arboriculture. (Barnes’ wife Laura was an enthusiastic horticulturalist.)

From Idea to Reality

That same year, Barnes purchased a 12-acre parcel of land in Merion Station, Pennsylvania from Captain Joseph Lapsley Wilson. For more than 50 years, Wilson had collected and cultivated over 200 specimens of trees—establishing one of the country’s first arboretums. Barnes hired the French American architect Paul Philip Cret to design a gallery building and attached residency, to be built within the arboretum. In 1940, Laura Barnes and botanist John Milton Fogg Jr. of the University of Pennsylvania began the Arboretum School of the Barnes Foundation.

With John Dewey as the honorary director of education, Barnes welcomed the first class of students to the Foundation in 1925. The collection by then also included one of the largest personal collections of art from African cultures in the United States displayed alongside works of American and European modernism. The opening of the Foundation was the realization of an educational trajectory that had lifted Barnes out of poverty in Philadelphia’s neighborhood “The Neck” through Central High School and the University of Pennsylvania to opening educational opportunities for anyone with a genuine interest in learning about art and its connection to lived experience.

The Barnes Method: Scientific Methods + Art Analysis

Exploring the relationship between art and the everyday is central to another project that Barnes pursued as his collection grew. Dissatisfied with contemporary methods of art history and analysis, Barnes found it necessary to develop an analytical framework for his own understanding and evaluation of art. Adapting aspects of formalism promoted by Roger Fry and Clive Bell, informed by the pragmatic philosophy of John Dewey and William James, and structured on the scientific methodology of his own medical education, Barnes developed what he called an objective method for art analysis: what we today call the Barnes Method.3

Strongly object-centered, the Barnes Method relies on close looking and critical thinking focused on the art object itself. Observation and analysis concentrate on a work of art’s visual qualities, such as the artist’s use of color, line, light, and space. Observations are made and suppositions proposed. These are measured back against the art object and refined, revised, or rejected. The combined effect of confirmed observations helps inform a culminating conclusion as to the work’s expressive effect. Conclusions are grounded in concrete experiential qualities. For example, a painted area may convey a sense of solidity, three-dimensionality, weightiness, set-ness, and containment. A still life by Cezanne, for instance, may express qualities of precariousness or instability, as objects with the above qualities are set on the inclined plane of a tabletop.

Figure 4: Paul Cézanne (French, 1839 – 1906), The Large Pear (La Grosse poire), 1895–1898, oil on canvas, The Barnes Foundation, BF190

Drawing expressive conclusions rooted in concrete, objective, experientially-based observations is a distinguishing characteristic of the Barnes Method. This clearly separates it from, say, Roger Fry’s formalism, which focuses exclusively on an analysis of a work of art’s form. In addition, the Barnes Method encourages objectivity, not allowing personal subjective preferences to influence critical judgement. Instead, the Method asks viewers to put aside individual likes and dislikes, and, to the degree possible, evaluate an object with clear unbiased reasoning.

Pursuit of objective analysis is one important way that the Barnes Method supports the relationship between art and medicine. For instance, how can analyzing a work of art, learning to see beyond an initial response to its subject, focusing instead on aspects that are concrete and verifiable, then finding language to describe our perceptions to others, relate to and perhaps improve diagnostic and communication skills in medical students and clinicians?

The Barnes Method in Medical Education

It was against this historical background that in 2018 work began on developing a program that would use the collection and methodology to explore issues and topics relevant to medical education, clinical practice, and overall well-being. The Barnes, with its collection of paintings, sculptures, furniture, wrought iron, textiles, ceramics, and other objects arranged in unique juxtapositions called ensembles, creates an unexpected environment for learners.

The varied size of gallery spaces and the range of objects drawn from global traditions, including a diverse collection of decorative arts, provide a rich and complex source of visual experiences. The collection functions like a laboratory ideal for exploring the interrelationship between aesthetic experiences with works of art and the lived experiences that fill our everyday lives. With their multivalent interpretations, the ensembles continue to challenge expectations and frustrate simple explanations. Learning within this space offers unique opportunities to cultivate critical thinking skills and gain valuable insights into patients with complex diagnoses and recovery journeys.

Figure 5: Gallery 4, West wall, The Barnes Foundation

Some may argue that medicine and art are antithetical—that medicine deals with science and facts and art deals with feelings and emotions. However, there is a large and growing body of research that shows multiple benefits of integrating the humanities into medical care and education.4 The gallery space can be a neutral environment for considering issues related to medical education and overall well-being while developing transferable skills for clinical practice.

Guided Experiences for Practitioners – and Patients

Guided experiences with works of art can provide medical students and early-career clinicians the means to confront challenging topics and improve interpersonal skills.5 As a medical professional progresses in their career, the benefits of spending time in art galleries can evolve to become a means of self-care helping to combat burn-out.6 Professions with high levels of stress, such as medical ones, experience increased rates of burn-out—a trend that dramatically increased during and in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. Research published in 2022 in the journal Mayo Clinic Proceedings, showed that 63% of physicians surveyed reported at least one symptom of burnout at the beginning of 2022—an increase from 38% two years earlier at the beginning of the pandemic, and compared to 44% in 2017 and 46% in 2011.7

Time spent in gallery spaces like the Barnes can have physical benefits for all—and patients in particular. Research8 has found that museums create value by catalyzing feelings of wonder, interest, curiosity, enhanced understanding, a greater sense of belonging, and perceptions of physical safety and serenity. Value is rooted in the ability of museums to use their collections in ways that make accessible to a broader public vast and diverse knowledge about the past, insights into present-day cultural identities, and opportunities for the creation of future creative expression—all of which are made manifest through the varied experiences that art collections support.

Research has shown universal well-being-related value across five dimensions (personal, intellectual, social, emotional, and physical) that are strongly correlated with perceptions of a satisfying and successful life.9 A vast majority of the public perceives that they derive universal benefits following a museum visit, indicating that these museum experiences have societal value of a duration of several days or longer.10

Art as Prescribed Treatment

After visiting art collections like the Barnes, a large majority of the public experience personal, intellectual, social, emotional, and physical well-being. And these universal benefits are strongly correlated with perceptions of a satisfying and a successful life. In the United Kingdom, doctors experimented with prescribing “therapeutic art or hobby-based treatments for ailments ranging from dementia to psychosis, lung conditions and mental health issues.”11 Doctors in Brussels prescribed museum visits to their patients who were struggling with stress due to the COVID-19 pandemic, with the hope of “alleviating symptoms of burnout and other forms of psychiatric distress.”12

Research conducted by colleagues at the University of Pennsylvania’s Positive Psychology Center suggests that “art museum visitation is associated with reductions in ill-being outcomes and increases in well-being outcomes.”13 It was in this environment of growing interest in connecting medical students, professions, and the broader public to the humanities that the Barnes began developing the Art, Well-Being and Medicine program.

The Art, Well-Being and Medicine Program at the Barnes Foundation

The Barnes Foundation was approached in 2017 by Dr. Sheldon Weintraub and his wife Margie who were interested in creating a legacy gift in Sheldon’s name. Sheldon, a retired physician who had trained as a Barnes docent, was in the last stages of terminal cancer. As a docent, Sheldon would occasionally welcome fellow physicians to the Barnes; together they would discuss the relationship between experiences they had with works of art and the practice of medicine. Building on these experiences, Sheldon and Margie created the Dr. Sheldon Weintraub Fund, which provided funding to support the development of the Art, Well-Being and Medicine program.

Simultaneously, Adrian Banning, an instructor in Drexel University’s physician assistant (PA) program, reached out with an interest in bringing first-year students to the Barnes for an art and medicine experience. Working with Banning and colleagues at Drexel, the Barnes program designed a series of gallery exercises around key concepts. Topics were chosen and researched, materials were workshopped to determine appropriate language and gallery experiences, curricular relevancy was determined, and related supporting materials were identified.

Six gallery-centered exercises were initially designed, with one added a year later. They are:

- Close looking. Exploring how spending time looking carefully at a painting might relate to clinical diagnostic skills.

- Critical thinking. Moving beyond set assumptions to deliberately and methodically explore problems or situations.

- Clear communication. Promoting a skill important between physician, patient, and family but also across the medical field and beyond.

- Collaborative problem solving. Emphasizing medicine as a team effort; valuing all voices and perspectives for a team to function effectively.

- Building empathy. Being open to truly hear and respond to others, or as Rita Charon, MD, PhD, and developer of narrative medicine writes, “the ability to acknowledge, absorb, interpret, and act on the stories and plights of others.”14

- Developing self-awareness. Recognizing both one’s personal skills and strengths as well as limits and biases in order to minimize the over-influence of either.

- Navigating ambiguity and addressing uncertainty. Focusing on building personal decision-making strategies in the face of potentially competing or conflicting outcomes. This exercise was added a year after the program began, on the suggestion of a returning third-year Drexel PA student.

Importantly, each exercise is accompanied by literature drawn from respected medical journals that supports and validates the exercise topic. In addition, colleagues at Drexel’s PA program contributed concrete examples of clinical relevancy outlined on each exercise document. It was essential that the experiences be enjoyable but also meaningful. Exercises were also intentionally designed to provide returning participants a variety of experiences.

Participants may work as a large group, but also in small groups, pairs, and individually. Among the program’s requirements:

- Participants are required by the exercises to engage in dialogue with their colleagues—sharing experiences and perceptions.

- Participants are also asked to make presentations to their colleagues, requiring their thoughts and ideas to be organized and clearly articulated.

- Groups participating in multiple visits are asked to engage in written reflection through journaling at the conclusion of each session. Between sessions, these participants are prompted to read their previous entries, reflect on them and the time between, and write more. Journaling allows participants to translate vague impressions into concrete ideas; their journal becomes a record of their evolving experience.

Example: The Rousseau Painting and Addressing Uncertainty

One topic that surfaces in nearly every Barnes program session is navigating ambiguous or uncertain situations. How are conclusions reached when more than one outcome appears equally valid? How are decisions made in the absence of all desired information?

…Which brings us back to our pair of PCOM medical students in gallery 19 and questions regarding the Rousseau painting (Fig. 1)—such as, “Who are these people? What is their relationship to each other? What is going on?” Paintings are ideal for addressing issues like this because they are very often themselves ambiguous. They present some information very clearly, but what that information adds up to is often unclear.

In the painting in question, a man and woman dressed in formal black clothes stand next to one another, exchanging a bouquet of flowers. They are in a wooded landscape behind a small flowering shrub and sinuous vine. This seems fairly straightforward. Yet, in the sky above, floating among the clouds, are the disembodied heads of a man and woman. Who are they? What relationship do they have with the standing pair? What is going on? And what is the relationship between the two standing figures? Are they brother and sister, wife and husband, or something else? Here the painting is opaque. Answers to these questions are not clear. We are left to decipher it as best we can.

Addendum. Rousseau painted this picture in 1899, the year after he married his second wife Josephine Noury. Both had been widowed; the heads in the clouds represent their former spouses, who Rousseau shows blessing the new union. However, this meaning is not clear from the painting itself. Rousseau’s inventive composition is open to various interpretations, making it ideal for this exercise. Rousseau was a self-taught artist.

Conclusion

Building a Repertoire of Tactics

Confronting challenging topics in a neutral space like an art gallery, where no real-world consequences exist, allows participants to focus on the process they undergo without concern for potential outcomes. They are free to test approaches and cultivate personal strategies, building a repertoire of tactics that they may draw on when needed in real-world situations. Programs like the Barnes’s Art, Well-Being and Medicine provide space and guidance to help participants develop important personal and professional skills.

Strengthening Well-Being

In addition, spending time in collections like the Barnes can build a greater level of comfort in this and similar spaces, particularly for those unfamiliar or naturally unsure in art collections. Upon concluding their participation in the Barnes’s Art, Well-Being and Medicine program, we hope participants will want to return to spaces like these for their own well-being.

References

- Wattenmaker RJ, Barnes AC, The Barnes Foundation. American Paintings and Works on Paper in The Barnes Foundation. The Barnes Foundation and Yale University Press; 2010. 18-19.

- Albert C. Barnes to Robert von Moschzisker, October 13, 1917. ACB Correspondence.

- Perthes WM. The Barnes method. In: Lucy M, ed. The Barnes: Then and Now. Philadelphia: Barnes Foundation Press; 2023:39-59.

- Mehta A, Agius S. The use of art observation interventions to improve medical students’ diagnostic skills: a scoping review. Perspect Med Educ. 2023;12(1):169–178. doi: https://doi.org/10.5334/ pme.20

- Naghshineh S, Hafler JP, Miller AR, Blanco MA, Lipsitz SR, Dubroff RP, et al. Formal art observation training improves medical students’ visual diagnostic skills. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(7):991-7. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0667-0

- Haidet P, Jarecke J, Adams NE, Stuckey HL, Green MJ, Shapiro D, et al. A guiding framework to maximise the power of the arts in medical education: a systematic review and metasynthesis. Med Educ. 2016;50(3):320-31. doi: 10.1111/medu.12925

- Engel T, Gowda D, Sandhu JS, Banerjee S. Art interventions to mitigate burnout in health care professionals: a systematic review. Perm J. 2023;15;27(2):184-194. doi: 10.7812/TPP/23.018

- Shanafelt TD, Wes CP, Dyrbye LN, et al. Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life integration in physicians during the first 2 years of the COVID-19 pandemic. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 2022;97(12). doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2022.09.002

- Research presented in May 2023 conference of the Institute for Learning Innovation, results not yet published.

- Falk JH, Dierking LD. Reimagining public science education: the role of lifelong free-choice learning. Discip Interdiscip Sci Educ Res. 2019;1(1). doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/s43031-019-0013-x

- Falk JH. The Value of Museums: Enhancing Societal Well-being. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers; 2022.

- Solly M. British doctors may soon prescribe art, music, dance, singing lessons. Published online Nov. 8, 2018. Available at: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/british-doctors-may-soon-prescribe-art-music-dance-singing-lessons-180970750/. Accessed November 28, 2023.

- Boffey D. Brussels doctors to prescribe museum visits for Covid stress. The Guardian. 2 Published online Sept. 2021. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/sep/02/brussels-doctors-to-prescribe-museum-visits-for-covid-stress. Accessed November 28, 2023.

- Cotter KN, Pawelski JO. Art museums as institutions for human flourishing. J Pos Psych. 2021;17(2):1-15. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2021.2016911

- Charon R. Narrative medicine: a model for empathy, reflection, profession, and trust. JAMA. 2001;286(15):1897–1902. doi:10.1001/jama.286.15.1897

Member since 2019 | JM14274

Member since 2019 | JM14274

NO COMMENT