The Power of Touch: Trust

By Brandon Ness, PT, DPT, PhD

For me, as a child, contentment arrived in the form of a pencil and paper. I drew pictures throughout my childhood. I continued to draw occasionally through college, but time limitations and other commitments led to a nearly 10-to-15-year post-grad absence from drawing. One afternoon while sitting on the porch with my family, I noticed a petunia had fallen onto the table from a hanging basket. I had a pencil nearby, so I picked it up and began to sketch. I noticed at first it was challenging to create an accurate representation of the contours and contrast of the flower petals, but gradually I was able to get back in the ‘zone.’ I shared my drawing with my family and heard myself describing how I translated my vision of the petunia to paper. It was this ability to connect with others through art in a unique, relatable way that made it so rewarding, and I was motivated to continue engaging with this familiar creative process.

Bridging Art With DPT Instruction

In my experience, I have also seen how art can have a substantial impact on the viewer in several ways, from drawing out various emotions to creating a means for deeper discussion or understanding. Hence, I set out to explore ways to bridge art with my current role as a core faculty member in a Doctor of Physical Therapy (DPT) program. In my quest for bringing art into my professional life, I thought about the physical therapy (PT) profession and some of the aspects that make it unique from other health disciplines. One concept that stood out was the many ways physical touch, or tactile perception, are utilized when performing the duties in PT. I decided to direct my art to the concept of physical touch as a foundation of trust between the patient and clinician.

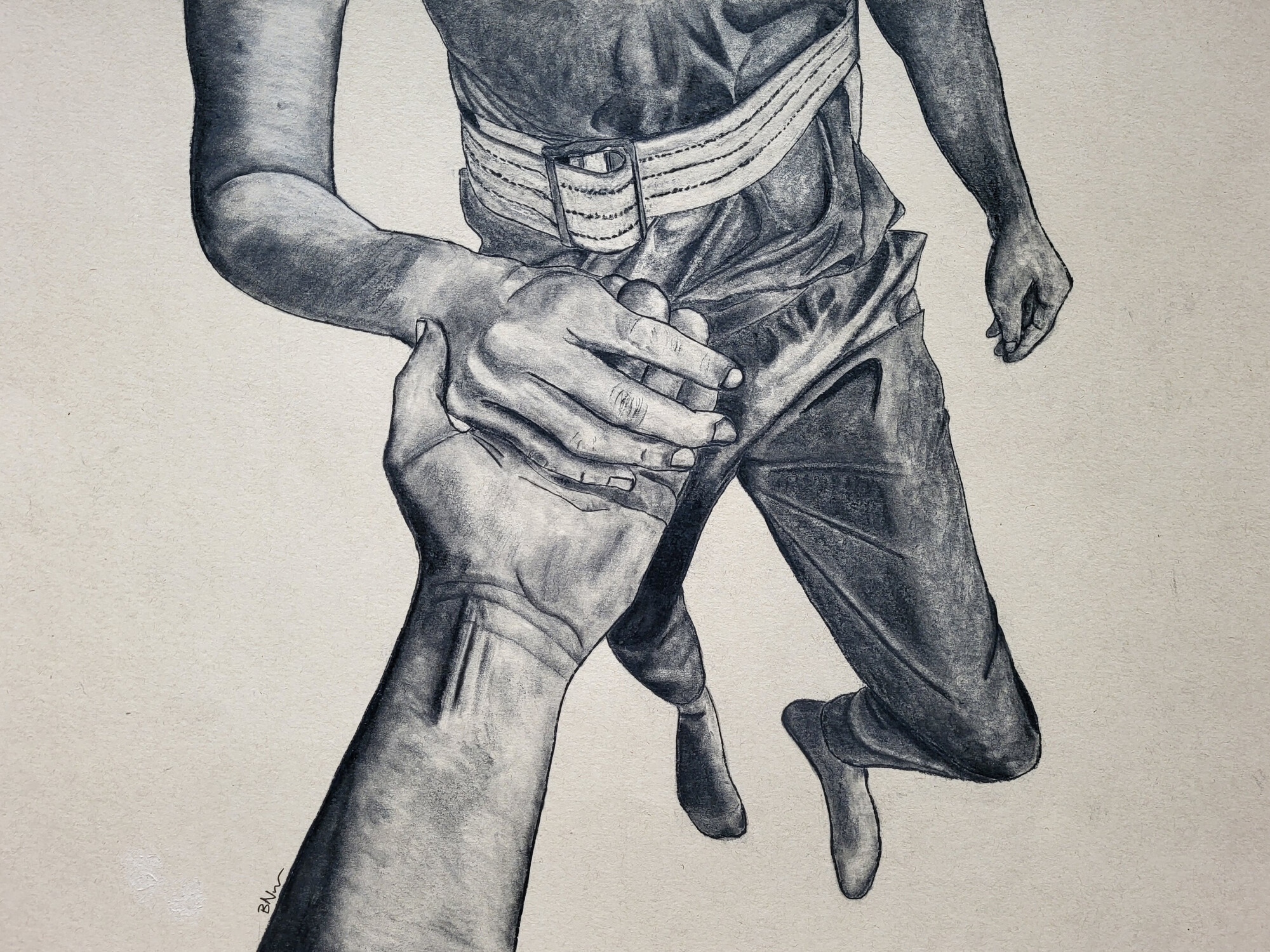

Figure 1: Drawing by Brandon Ness; The Power of Touch: Trust; compressed charcoal on paper.

Illustrating Trust Through Touch

In formulating ideas to illustrate the construct of trust through physical touch and the nuances of physical touch in PT practice, one scenario stood out. In this image that I created (Figure), the clinician provides light hand hold while the patient maintains a single limb stance—communicating the idea that trust is an extension of physical touch, and vice versa. The physical therapist’s open hand with light touch demonstrates warmth and confidence in the patient while still being available to physically support the patient if needed.

In order to interpret the subtle changes in a patient’s response during a dynamic clinical scenario such as this, one must appreciate the nuances, intent, and value of physical touch in this context. During this intervention, the patient trusts the prescribed exercise will help them reach their goals in a manner that maximizes benefits while simultaneously minimizing risk. By varying the amount of touch during the intervention, it displays the physical therapist’s confidence and trust in the patient as the patient gains independence as part of the rehabilitation process. The decision-making process of when and how to use physical touch during patient care is an important learned skill, and this drawing helps to encourage clinicians or students to consider its application and desired outcome.

Formulating the Image

I recall that as I was completing this drawing, there were several decisions that needed to be made. Initially, I was going to provide a detailed representation of the hands only, while leaving the other objects vaguer (gait belt, clothing, etc.), as I thought: 1) a focus specifically on the aspect of physical touch would resonate differently with the viewer, and 2) I had never drawn clothing in great detail before! The clothing, although somewhat technically difficult, became one of my favorite aspects of the drawing, as it adds a layer of texture and movement that otherwise would have been absent. This decision, and the reward it produced, adds motivation to take more risks during the creative process in the future.

Although I have never sculpted, the process of charcoal drawing, blending, and removing/adding contrast makes me think there are some similarities with sculpting. There were parts of the drawing that initially did not turn out how I had intended, but the ability to modify and ‘sculpt’ certain parts of the drawing allowed flexibility to take certain creative risks to a degree. One example, again, was the clothing. The pants were initially quite dark throughout, which made it difficult to discern and appreciate the details of the folds/tension of the fabric. I decided to lighten the fabric by removing some of the charcoal with the intent to allow the viewer to notice the position of the lower extremities with greater ease. This flexibility that accompanies charcoal drawing is one aspect that makes it an enjoyable medium to use in this way.

Visible Thinking

To better appreciate how this artwork might inform one’s teaching/practice, I met with several DPT students to garner their perspective. We met virtually as a small group and went through the Visible Thinking process of ‘See, Think, Wonder’ from Harvard University.1 This strategy encourages students to carefully observe what is in front of them, make thoughtful interpretations and express their viewpoints, and create a sense of curiosity and inquiry.

Among medical learners, the use of visual thinking strategies may improve several attributes relevant to clinical practice, including our skills in observation, interpretation, and critical thinking;2-5 tolerance for ambiguity;6 fostering of empathy;6 and development of a sense of wonder.7 Developing wonder among medical students has been promoted due to its several potential benefits, such as fostering the delivery of humanistic patient care, developing a commitment to lifelong learning, and encouraging innovation.7,8

Student Insights

After a brief period of quiet viewing, the students discussed their observations of the artwork. The first theme that emerged was the notion of helping (from the physical therapist), but also trusting and allowing the patient to use assistance as needed. This concept was further explored by the supportive hand hold; the patient wearing a gait belt, but it’s not being used for support by the physical therapist; and the positioning of the physical therapist in front of the patient versus directly to the side or behind. Some felt the scenario reminded them of a dance, where one partner would lead while the other followed.

The concept of trust was mentioned on several occasions, even without the students knowing the title of the artwork. The students also pointed to the lack of facial cues and having to rely on the patient’s body posture to appreciate various qualities of this task. Was this task challenging? Enjoyable? Engaging? Hearing reflections through the lenses of DPT students helps to inform my teaching by encouraging me to adapt based on their current level of understanding, and how their questions or perspectives may evolve over time as they are introduced to diagnoses, rehabilitation techniques, and experiences from clinical education.

One aspect of the artwork that was noticed among the students is the lack of a visual background or setting for this patient-clinician encounter. Honestly, there was not much intentionality behind this, but as I spent more time with the drawing and hearing the student feedback, I believe this allows the viewer to imagine this scenario occurring in a variety of settings (outpatient, hospital, etc.), so the viewer is not limited in their interpretation by setting alone. The lack of background, along with other features in the drawing, may contribute to the sense of wonder and its relevance to clinical practice as discussed earlier.

Clinical Questions

After having time to sit with the drawing, the viewer may begin to question the reason, or diagnosis, for the patient being in PT, and why the patient is specifically performing this task. The viewer scans for clues in the drawing that may help fill in the necessary details to lead them down one diagnostic path versus another. The mystery around the patient’s condition also encourages the viewer to recall various patient presentations discussed in the classroom or observed clinically, in order to develop a working hypothesis when assimilating various pieces of information from the patient’s history and examination. One of the aims of this drawing is to ignite the critical thinking process, which is often threaded throughout DPT curricula.

Conclusion

In conclusion, my reintroduction to drawing has been rewarding on multiple levels, most notably the enhanced ability to connect with others and share ideas. As an educator, artwork allows me to better understand the student perspective through facilitated discussion—offering insight to adapt my teaching practices to meet their learning needs and provide an opportunity for further conversation in clinical reasoning. I am grateful to have found a creative outlet that allows me to explore concepts in clinical practice and education from a different perspective, including the construct of trust through physical touch in physical therapy practice.

References

- Harvard Graduate School of Education. A Thinking Routine – See, Think, Wonder. Available at: https://pz.harvard.edu/sites/default/files/See%20Think%20Wonder_3.pdf. Accessed March 1, 2024.

- Agarwal GG, McNulty M, Santiago KM, Torrents H, Caban-Martinez AJ. Impact of Visual Thinking Strategies (VTS) on the analysis of clinical images: a pre-post study of VTS in first-year medical students. J Med Humanit. 2020;41(4):561-572. doi:10.1007/s10912-020-09652-4

- Naghshineh S, Hafler JP, Miller AR, et al. Formal art observation training improves medical students’ visual diagnostic skills. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(7):991-997. doi:10.1007/s11606-008-0667-0

- Dolev JC, Friedlaender LK, Braverman IM. Use of fine art to enhance visual diagnostic skills. JAMA. 2001;286(9):1020-1021. doi:10.1001/jama.286.9.1020

- Schaff PB, Isken S, Tager RM. From contemporary art to core clinical skills: observation, interpretation, and meaning-making in a complex environment. Acad Med. 2011;86(10):1272-1276. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e31822c161d

- Bentwich ME, Gilbey P. More than visual literacy: art and the enhancement of tolerance for ambiguity and empathy. BMC Med Educ. 2017;17(1):200. doi:10.1186/s12909-017-1028-7

- Zheng D, Yenawine P, Chisolm MS. Fostering wonder through the arts and humanities: using visual thinking strategies in medical education. Acad Med. 2023:256-260. doi:10.1097/acm.0000000000005519

- Evans HM. Wonder and the clinical encounter. Theor Med Bioeth. 2012;33(2):123-136. doi:10.1007/s11017-012-9214-4

Member since 2019 | JM14274

Member since 2019 | JM14274

NO COMMENT