Medical school can install students in locales both familiar and unfamiliar: the darkened hush of a lecture hall, the sheeted tables of an anatomy lab, the beeping monitors crowding an ICU. But students may now also find themselves before a Pollock or a Kahlo, contemplating art in the vaulted halls of a museum exhibit. Medical schools are increasingly partnering with museums to formally integrate the arts and humanities into their curricula. Recently, I had the opportunity to pilot such a program—a visual arts elective at Emory University, called “Outside the Frame.”

Museum-based education is far from a new phenomenon in undergraduate medical education (UME), but many such programs rely on the sole use of Visual Thinking Strategies (VTS), a facilitated method of guiding students in analyzing an art object. VTS employs three main questions to achieve its aims:

- What is going on in this image?

- What do you see that makes you say that?

- What more can we find?

Through articulating their ideas and grounding them in heuristic evidence, students learn to continually revise their interpretations while building on the viewpoints of others. Ample evidence exists in the literature that VTS in health professions education can effectively enhance observational skill, communication, perspective-taking, critical thinking, and empathy.1,2,3

Context: An Underexplored Area

While true that a minimalist approach to VTS allows educators across institutions to more easily adopt its pedagogy, this strength simultaneously forecasts a key weakness: the tacit assumption that art can be accessed through visual cues alone. VTS can serve as a useful starting point to grease the skids and usher students into a space of inquiry; however, current imaginings of museum curricula in many UME programs abstain from elevating the role of context to explore the pedagogy’s full potential. A proposed fourth question for VTS:

- What contexts may lie beyond what we see?

Although a context-free standard may nurture an appreciation for multiple perspectives and avoid premature closure, it also arrives at this point by intentionally disaggregating from any historical, social, political, or ethnographic background that could potentially imperil an “open” reading of the work. In so doing, it not only deprives itself of the opportunity to interact with the diverse disciplines intersecting in the museum space that can advise on such topics, but also denies students the ability to productively engage with context.

Triangulating Perspectives

Far from just a geographic or physical setting, context refers to the varying conditions and ideologies under which our institutions function, from hospital funding to heteronormativity. As the COVID-19 pandemic has sufficiently foregrounded, the increasing complexity of healthcare challenges us to honor these contexts by adapting a curriculum from an objective, metrics-based approach to a more “systems”-based one that can triangulate data and perspectives from multiple sources.

Beyond cultivating students’ diagnostic skills and building outsized reliance on individual powers of observation, modern medical training needs to encourage students to engage with unfamiliar contexts outside the boundaries of personal experience. By considering the specific academic codes, debates, and practical frameworks of art history and other social sciences disciplines, students could venture more confidently beyond the primacy of their medical training and integrate knowledge from a broader disciplinary toolkit. Such an approach would allow learners to re-envision uncertainty as not merely something to be ‘tolerated’ but actively explored as an essential source of intellectual curiosity—something of which medical trainees have no shortage.

Our Multidisciplinary Approach

Our curriculum, therefore, actively sought out and queried outside expertise from faculty broadly ranging across multiple departments, such as art history, classics, psychology, and history. In our final session, we gathered in the conference hall at the Carlos Museum, where art history professor and curator Dr. Rebecca Stone gave a lecture on shamanism in ancient indigenous art and its role in healing, titled: Plant Teachers, Shamanic Visions, and Death.

I sensed some apprehension in the room as the lecture proceeded, and couldn’t help but feel it myself, having just emerged from a lecture on soft-tissue infections and broad-spectrum antibiotics.

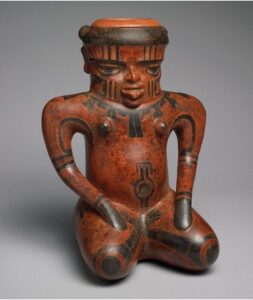

Figure 1. Doe shaman effigy. Ex coll. William C. and Carol W. Thibadeau, Michael C. Carlos Museum, 1991.004/344. Photograph by Bruce M. White.

Cast against the absolutizing categories of side effects and dosage requirements, the topic of shamanism seemed impossibly distant and nebulously vague. Gradually, however, I observed students’ reactions to the content transform from guarded bemusement to wonder—as what initially appeared to be an extended non-sequitur began to draw fascinating parallels to relevant clinical material.

The lecture touched on various pieces in the Carlos collection relevant to shamanism, such as the Deer-Human effigy in Figure 1. Hailing from modern-day Costa Rica and Nicaragua, this work depicts a woman in a typical shamanic trance pose, seated with crossed legs and her hands resting on her thighs. On closer inspection, however, conspicuously non-human features emerge: her “hands” have coalesced into dark hooves, and knobby protrusions bud from either side of her head like antler stumps. These features contradict her still-human feet, which are painted directly onto her thighs rather than carved like the hooves, as if her anthropocene characteristics are literally receding into the background in light of her transformation. She reflects an important visual theme common to many ancient American art styles—that of shifting form, usually into animals that signify inhuman physical prowess, like heightened senses, strength, and speed. These qualities codify a larger spiritual shift, considered important especially for shamans as they leave the boundaries of their physical form to navigate the spiritual world.

As Dr. Stone explained to us, shamans are healers who have been ascribed with such powers because they survived, and thus emerged “victorious” from, physical challenges. Having transcended the limitations of the terrestrial, these figures now tread the demarcations separating life from death, male from female, human from animal.4

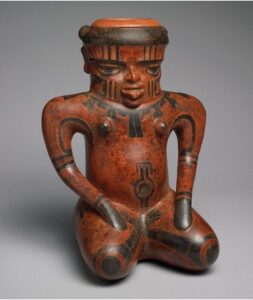

Another effigy we discussed adopts a similarly-meditative hands-on-knees pose, but with several marked differences: the eyes are slit in a faraway “trance” state, and the head strangely ends in a cap-like top (Fig. 2). Moreover, whereas the former figure had unmistakably female characteristics, this one is more ambiguous, with features suggestive of both male and female gender. Students were then treated to several relevant informational tidbits: 1) that the cap-like head alluded to the characteristic tops of psilocybin mushrooms (Fig. 3) ritually used by shamans for their psychedelic effects; 2) the figure was thought to depict an individual with Klinefelter syndrome, a condition in those male-born with an extra X chromosome.

Figure 2. Kneeling Intersexed Kyphotic figure. Ex coll. William C. and Carol W. Thibadeau, Michael C. Carlos Museum, 1991.004.512.

Figure 3. Psilocybe, Stropharia spp.

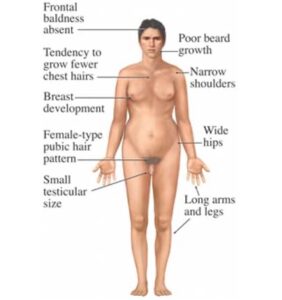

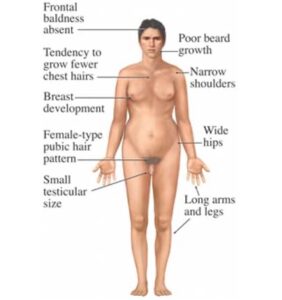

Figure 4. Symptoms of Kleinfelter Syndrome.

Noises of excited recognition rose from the group. The brief, bulleted takeaways on Klinefelter’s we had been exposed to thus far had largely been lensed through a Western science perspective, which portrays the condition as a pathology terminating in several unfortunate outcomes: lower IQ, infertility, erectile dysfunction, hunchback, a higher mortality rate. These symptoms, easily summarized by the unsuspecting learner as ‘disfigurements,’ cast a similarly negative pallor on some of its other hallmarks: wide hips, a taller stature, gynecomastia (male breasts), and small testes (Fig. 4).

And yet, to shamanic culture, these were not so much disfigurements as sublime signs of an expanded, transcendent existence—someone who could navigate between the binary constructions of sex. These new factoids not only painted the disease in a new light, but also built on the previously-given information that ingestion of mushrooms was associated with enhanced visionary powers. Importantly, the figure (Fig. 2) was portrayed as not just taking mushrooms, but as being in the process of transforming into one. In so doing, it depicts the shaman as not merely passively submitting to the drug’s influence, but also as metaphorically embodying the drug’s very power and potential.

Context Exposing Prejudice

Learning the context underlying these effigies exposed our occupational prejudices in more ways than one: we were forced to revise our thinking about not only Klinefelter’s as a disease, but also on what such a ‘diseased’ state even implies in our medical culture. A tendency toward classification and closure permits physicians to see patients as a means to an end—to encounter someone as a composite of informational soundbites that must satisfy, and ultimately reproduce, a familiar illness script, narrative, or pattern. The ‘ill’ person thus becomes subjected to the superior ordinance of disease, which decrees a predetermined, biologically-fated outcome that implicitly denies patients their individual agency. But for shamans, disease is not a terminal end-point at which all possibility converges to a halt, but rather a beginning: an aperture through which one transforms, grows fluid, gains new insight and transcends boundaries. What is at stake is not a narrowing down of possibilities, but their broadening—to see further, feel deeper, and journey into new realms.

Reconsidering Ethics of Care

More often than not, modern medicine endeavors to narrow the realm of possibilities. Medicine is a system of categories; when we diagnose a patient, we tend to apprehend them not in their individuality but in their generality, the degree to which their physical description complies with a set of preconceived assumptions and rules. This can be a good thing; certainly, consistency breeds reliability, which is what we want when diagnosing illness, prescribing treatments, or making recommendations. However, this attraction to sameness, to what confirms our bank of pre-existing knowledge, can dangerously skew our ethics of care.

An aversion to the foreign is a part of medical culture. Throughout our training, students are taught to rank the usefulness of their scientific endeavors through the quality of evidence produced. Otherwise known as “evidence-based medicine,” this dogma twins that of VTS in that it largely accounts for detectable presences—of visible signs, symptoms, and outcomes. However, the true reality is that at every stage between observation and interpretation, a scrim of ideologies and values filter through certain features without manifesting the absences—the omitted narratives, the alternative worldviews. A privileging of only that which can be personally seen, inferenced, and proven can lead to a hierarchized view of knowledge production, creating an epistemic gap that siloes and isolates trainees from the fundamentally nuanced and human nature of the work we do.

By exposing students to these unfamiliar cultural contexts, we did not necessarily intend to encourage belief in shamanism, or the valuing of disease as ‘good’ and empowering. Rather, we were trying to show them that the layering of context can expand, rather than restrict, one’s horizons and capacity for interpretation. To understand that other cultures may elevate those we deem ‘unfortunate’ or anomalous can challenge us to suspend our own frames of reference while validating the patient as someone who is also continually deriving meaning from their embodied condition.

As future physicians, trainees must understand that the ‘hidden curriculum’ of medical education lies not in mastering or demonstrating competence in the unfamiliar, but in learning how to invite in, and partner with, this otherness. To take a page out of shamanic culture: the boundaries of self are always only the beginning of the story.

Member since 2019 | JM14274

Member since 2019 | JM14274

NO COMMENT