Introduction

Horace Pippin began creating art as a hobby in his childhood; this practice later served as an important force in both his physical and mental-health rehabilitation. This article discusses how Pippin’s paintings reflect a range of his experiences and demonstrate the power of art as a form of healing and communication.

Horace Pippin was born in West Chester, Pennsylvania, on February 22, 1888, to Harriet and Horace Johnson Pippin. He was born as a free man 23 years after the official end of slavery. When Pippin was two years old, his family moved to Goshen, New York—but he would return to West Chester in his adult years. He was a descendant of slaves and domestic workers. Pippin began to draw at an early age; however, since his parents were domestic workers, they could not afford basic art supplies. Pippin’s resourcefulness and determination differentiated him from his peers. To find ways around his financial limitations, he participated in several drawing competitions. In 1898, when he was 10, he won a box of crayons in a contest sponsored by an art supplier, which allowed him to continue coloring—an activity he loved.1

Pippin’s artwork, often described as primitive or naïve, became an instrument for the expression of his creative ideas; he said that he was painting what he literally saw inside his head. “The pictures… come to me in my mind,” he said, “and if to me it is a worthwhile picture I paint it… I do over the picture several times in my mind and when I am ready to paint it I have all the details I need.”1 For Pippin, what started as a hobby developed into a tool for personal healing as well as an instrument to speak out against racial inequity.

World War 1: Physical and Emotional Trauma

In June 1917, at almost 30 years of age, Pippin volunteered for the 15th New York National Guard, later renamed the 369th Infantry Regiment and nicknamed the Harlem Hellfighters.2 The Hellfighters eventually became a highly-decorated infantry regiment in World War 1. They were assigned to the 16th division of the French army because many white American soldiers refused to serve with them.3 This was the Jim Crow era, with many state and local laws enforcing segregation; therefore, this response was not unexpected. At this time, US military leadership was predominantly white, and many officers doubted that black people were intelligent or courageous enough to fight. According to the US national archives, it is estimated that of the almost 400,000 African Americans who served in WWI, only about 10 percent fought in battle.2,3 However, Pippin’s regiment did serve on the front lines—with distinction.

The 369th Regiment quickly proved its courage and combat skills. Initially nicknamed the “Black Rattlers” because of the insignia (black rattlesnake) on their uniforms, the French later called them “Men of Bronze” due to their fearlessness during battle.3 It is believed that the nickname “Hellfighters” was given to them by the Germans because of their courage and ferocity. The Harlem Hellfighters spent 191 days in the front-line trenches, spending more time in continuous combat than any other American unit of that size.3

In September 1918, Pippin was shot in the right shoulder by a German sniper. He fell to the ground, bleeding profusely. A French soldier seeking to help was shot dead and fell on top of Pippin, who was unable to remove him. After spending hours in the rain, he was rescued, but he lay on a stretcher overnight, exposed to the elements, before being evacuated to a hospital. The bullet shattered his shoulder; as a result, he spent the rest of his time at war recovering in a French hospital. Pippin was awarded a Purple Heart after his service because of the injuries he sustained in battle. Discharged that year with a steel plate in his shoulder and his right arm virtually paralyzed, Pippin returned to civilian life in West Chester—shattered both physically and psychologically.

Post-War Return to Art: Physical Recovery and an Ongoing Battle

After returning to the United States with a Purple Heart and an Honorable Discharge, Pippin faced yet another battle—that of ongoing racism and segregation. A decorated veteran, he still was only able to get odd jobs. He returned to Goshen with his small pension, no house, no job, and in pain.

However, he found happiness through marriage. He wed Jennie Ora Featherstone Wade, a twice-widowed woman raising her 6-year-old son alone. Jennie’s extended family lived in West Chester, Pennsylvania, so it was an easy decision for the couple to move there to build a life. Although he could not lift his arm above his shoulder and had little strength in his right hand, he helped where he could. Pippin worked at a segregated YMCA, started a Black boy scout troop, and organized an all-Black football team. He enjoyed attending meetings at the American Legion, a non-profit group working with veterans and their families. His love of music led him to create an American Legion drum corps, which he led.

Like many men who fought in the war, Pippin experienced “shell shock,”4 which we now know as Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). He was advised to write about his thoughts by other members of the American Legion, but the writing did not calm his mind. He wanted to go back to making art, but he couldn’t hold a pencil in his right hand. One winter as he sat by a cook stove, he picked up a hot poker and outlined a rough image on wood. Through a painstaking and difficult learning process, he devised a method of using his left arm as a support for his right hand clasping a paintbrush. This rough attempt convinced Pippin that he could return to making art.

By 1930, he had begun to teach himself to paint with oils, first on discarded cigar boxes, or by burning images onto wood panels using a hot poker (a technique called pyrography), and then applying oils.

In one of the few autobiographical accounts by a black soldier to come out of World War I, Pippin related his combat experiences in matter-of-fact terms. In books illustrated with pencil and crayon drawings of marching troops, soldiers wearing gas masks, exploding shells, and aerial dogfights, he recorded nightmarish memories of war on the Western Front. Pippin’s compelling World War I notebooks can be viewed online at the Smithsonian Institution’s Archives of American Art.

Art as Therapy

Perhaps unknown to him at the time, Pippin employed occupational (or rehabilitative) therapy practices (treatment of injuries, illness, or disabilities through the therapeutic use of everyday activities) in his quest to restore his war-broken mind and body. Painting, for him, became a means of therapy for his horrendous memories of war, and a way of dealing with his paralyzed extremity. Pippin’s postwar notebooks, letters, and journals, now housed at the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, explain his experiences after his return home from war, and make clear the importance of art in his life. “When I was a boy I loved to make pictures,” Pippin wrote, but war “brought out all the art in me… I can never forget suffering and I will never forget sunsets. So I came home with all of it in my mind and I paint from it today.”5

Pippin’s Timeless Imagery

Before departing for World War I, the Harlem Hellfighters were refused permission to participate in the farewell parade … known as the Rainbow Division because they were told that black was ‘not a color in the rainbow.’3 Their extraordinary courage in battle earned them fame in Europe and America, with multiple members of the regiment receiving awards from the French and American governments. After they returned home, they were rewarded with a victory parade. New Yorkers of every race showed up in large numbers to celebrate the Harlem Hellfighters as they marched up Fifth Avenue in Manhattan. However, this newfound fame did not last long. The story of the courageous Harlem Hellfighters has largely been erased from the awareness of Americans and the world.3 The story of the Harlem Hellfighters is not widely discussed in contemporary American culture. The works of Horace Pippin celebrate this history and draw national attention to these heroes.

Truth From the Front Lines

Nearly 15 years after he returned home from the war, Pippin created the painting The End of War: Starting Home (1930) (Figure 1). In this painting, Pippin condenses the terrifying episodes of war documented in his journals, showing images of combat fear, battle, and most importantly, the surrender of German troops. He included images of tanks, guns, hand grenades, gas masks, and other tools of war, alluding to the technological advances that made the war more brutal than any before it.6

FIGURE 1: Horace Pippin, The End of the War: Starting Home. 1930-33, oil on canvas, 26 x 30″. (Image courtesy of The Philadelphia Museum of Art.)

Perhaps the most important part of this painting for Pippin is his depiction of the African American soldiers. Pippin painted them to almost blend in with the background; perhaps this was his way of depicting how the efforts of African Americans in the war were often overlooked and given little recognition. They fought for a country that didn’t seem to appreciate their efforts even though they had proven themselves as American heroes and worthy soldiers.

A Direct and Powerful Statement

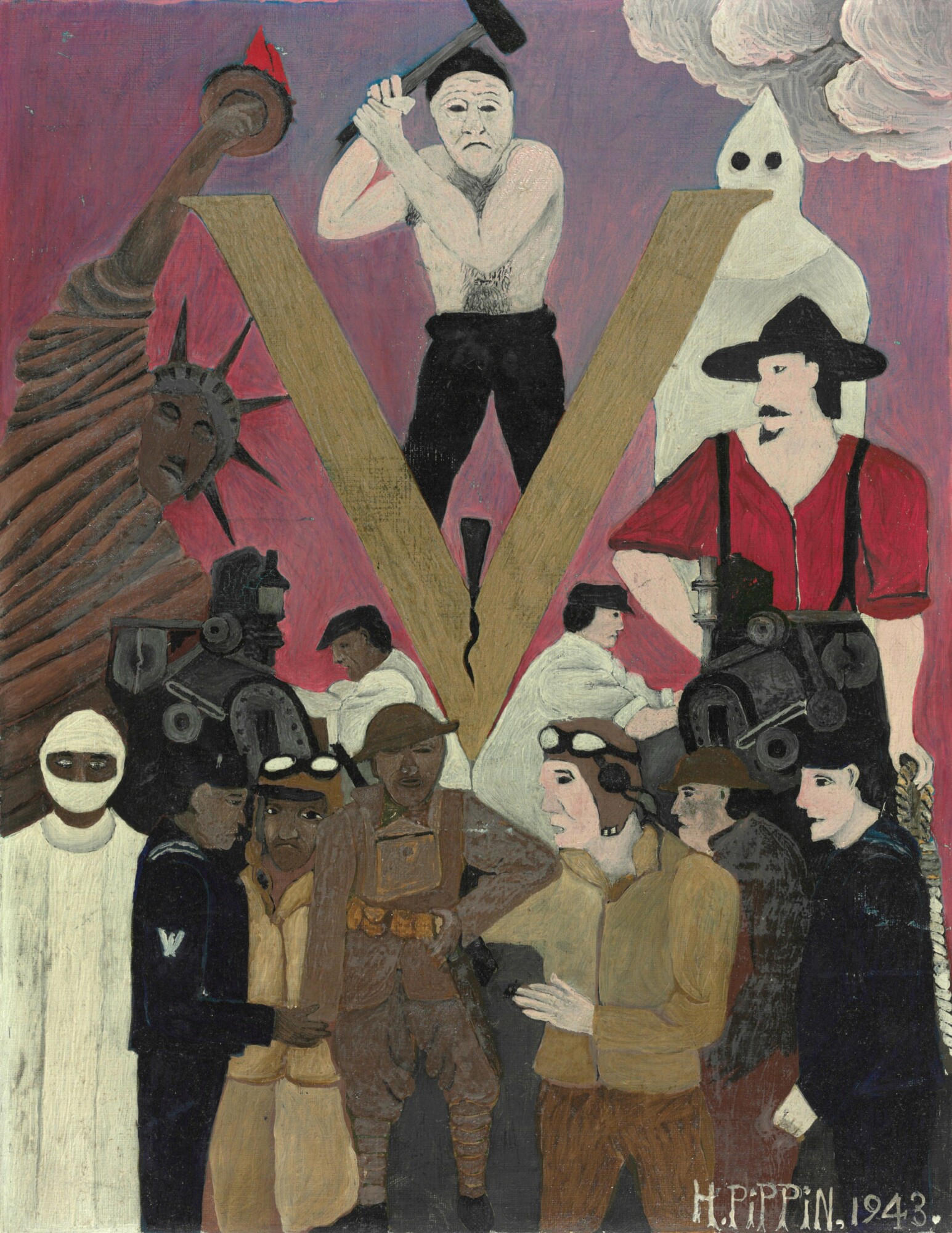

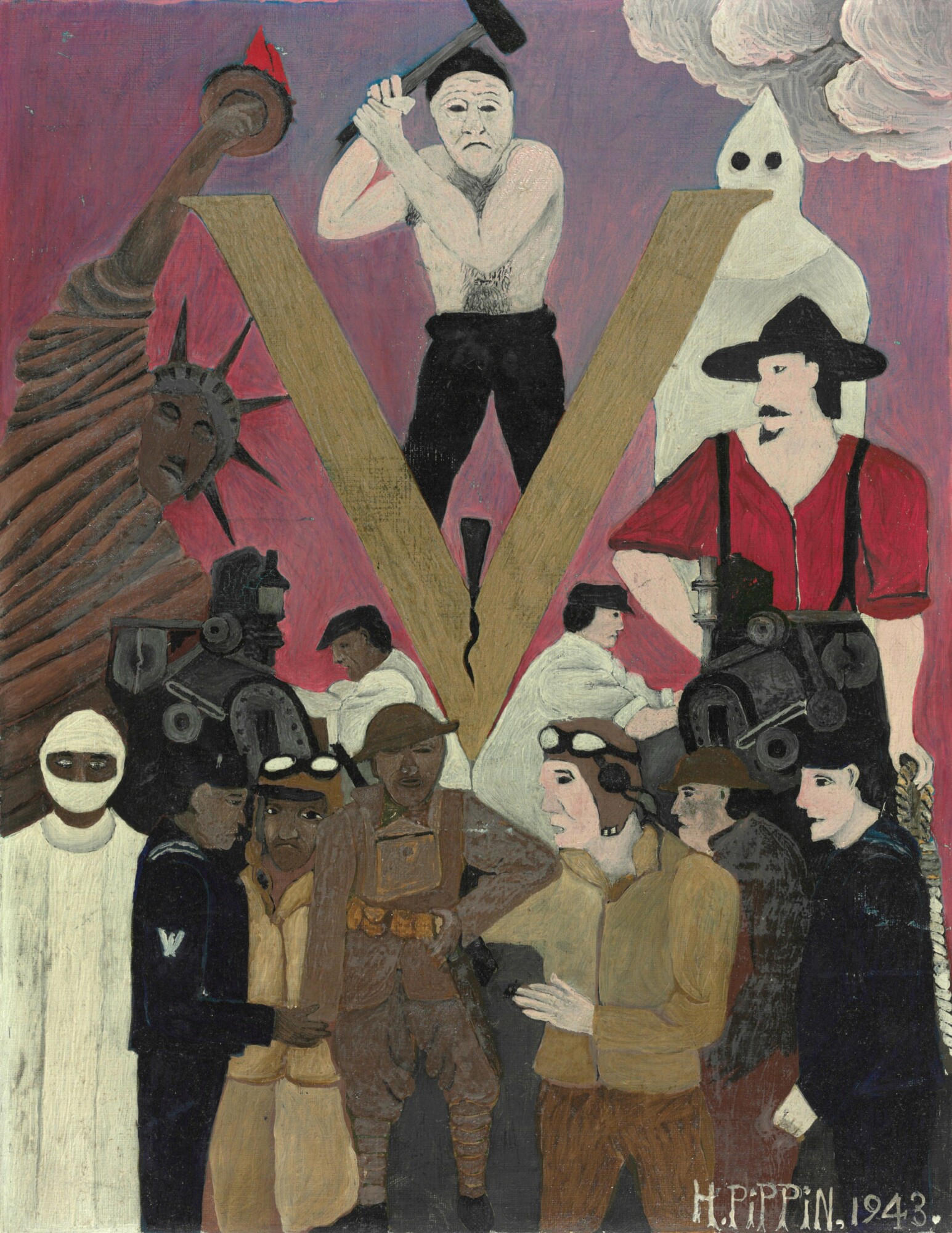

The painting Mr. Prejudice (1943) (Fig. 2), would become what is Horace Pippins’ strongest and loudest statement about racial inequality in the US. Deeply affected by his experiences as a soldier in a segregated troop during World War I, and the poor treatment he and other African American troops received after they returned home, Pippin was moved to make this painting when he noticed that this treatment of African American soldiers persisted into World War II.7

FIGURE 2: Horace Pippin, Mr. Prejudice, 1943. Oil on canvas, 18 x 14″. (Image courtesy of The Philadelphia Museum of Art.)

At the top of the painting is a menacing white man with an axe above the “V.” The “V for victory” was a gesture and phrase coined by Winston Churchill during World War II that took root in the US, especially after the bombing of Pearl Harbor. In the African American community, this became a double V, which represented victory in the military conflict abroad as well as the racial conflict at home. The axe held by this menacing white man has created a crack in the V, which divides not just it but the entire painting equally in two. To the left of the painting are African American symbols and to the right, the realities they faced due to racism. To the left of the painting is a black Statue of Liberty, which signifies the freedom and liberty that African Americans have been denied.

At the base of the V is an African American machinist to the left and a white one to his right with their backs turned to each other. In the bottom left, there are four African American men: a doctor, a naval officer, an aviator, and an infantryman (from left to right). To the right of them are three white men who are also involved in the war but are facing the African American men like they need to keep an eye on them. Also seen to the right of the V in this painting is a man in a red shirt holding a noose (a reference to the lynchings faced by Black people during this time) and staring intensely at the Statue of Liberty. Right above him is a person in the signature white robes of the Ku Klux Klan—a group whose numbers increased dramatically in the US after World War II.

This painting shows the dramatic contrast and dangerous circumstances that made up the lives of African Americans during this era.8 Through it, Pippin illustrates what life was like, and the hope of what it could be, calling for liberation and a better existence for African Americans through cooperation between races.

Post-War Return to Art: Scenes of Everyday African American Life

In the nineteenth century, the legal status of African Americans underwent radical changes, they were freed from slavery and began to enjoy some rights as citizens. Despite these changes, many demographic characteristics of African American life were no different from the mid-1800s. At this point, three-quarters of black households in the US lived in rural areas.9 Parents worked on farms with their children, who were very unlikely to attend school. By the late 20th century, African Americans had become less concentrated in the rural south and had better jobs but were still relatively disadvantaged in terms of education, labor-market success, and home ownership. 9 The wealth gap between whites and blacks continued to reflect historical patterns. African Americans struggled to acquire wealth, which made it harder to buy homes, especially due to real estate discrimination. They lived in poor neighborhoods, in houses in terrible condition.9 Horace Pippin’s 20th-century paintings reflected this reality.

Racism’s Effects Brought Home

In 1940, Horace painted Supper Time, an intimate description of everyday African American family life (Fig. 3).

FIGURE 3: Horace Pippin, Supper Time. c. 1940, Oil on burnt wood panel. 12 x 15 1/8 in. (Image courtesy of the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Burnt onto repurposed planks using a hot poker before color was added, this laborious process replicates the hardship depicted in the painting. The image shows a man and a child sitting at a table while a woman seems to be serving them a meal. There is a frying pan sputtering in the background and clothing hanging on a line to dry in the humble home. The house in the painting was made of mismatched planks, depicting the poverty that prevented African Americans from adequately repairing their homes. Pippin brilliantly uses color to guide the eyes of the viewers across the painting. From left to right we see white clothes hanging on a line, a child in white clothes, white cups and plates, and a woman in a white apron and scarf. Pippin also contrasts the pink shirt on the man with the blue dress on the woman. The woman’s dress contains dark shadows in her underarm area, suggesting repetitive wear and perspiration. This detail brings attention to the strength shown by the woman as she works through difficult conditions to perform her chores for the family. In Supper Time, Pippin simultaneously documented the strength and resilience of African American families while honestly depicting the environments in which they were forced to live. He calls attention to these debilitating disparities that existed throughout his lifetime.10

A Final Self-Portrait?

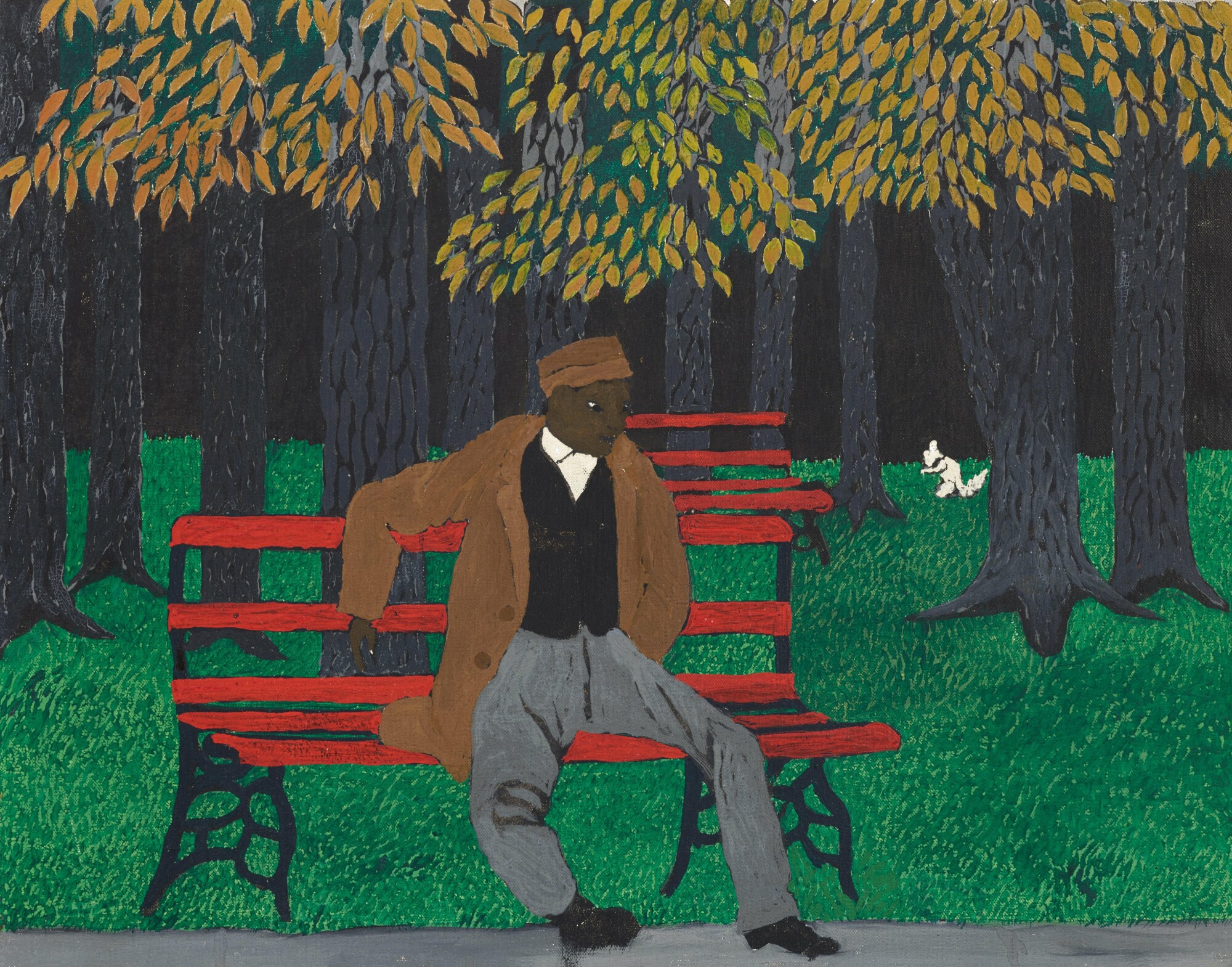

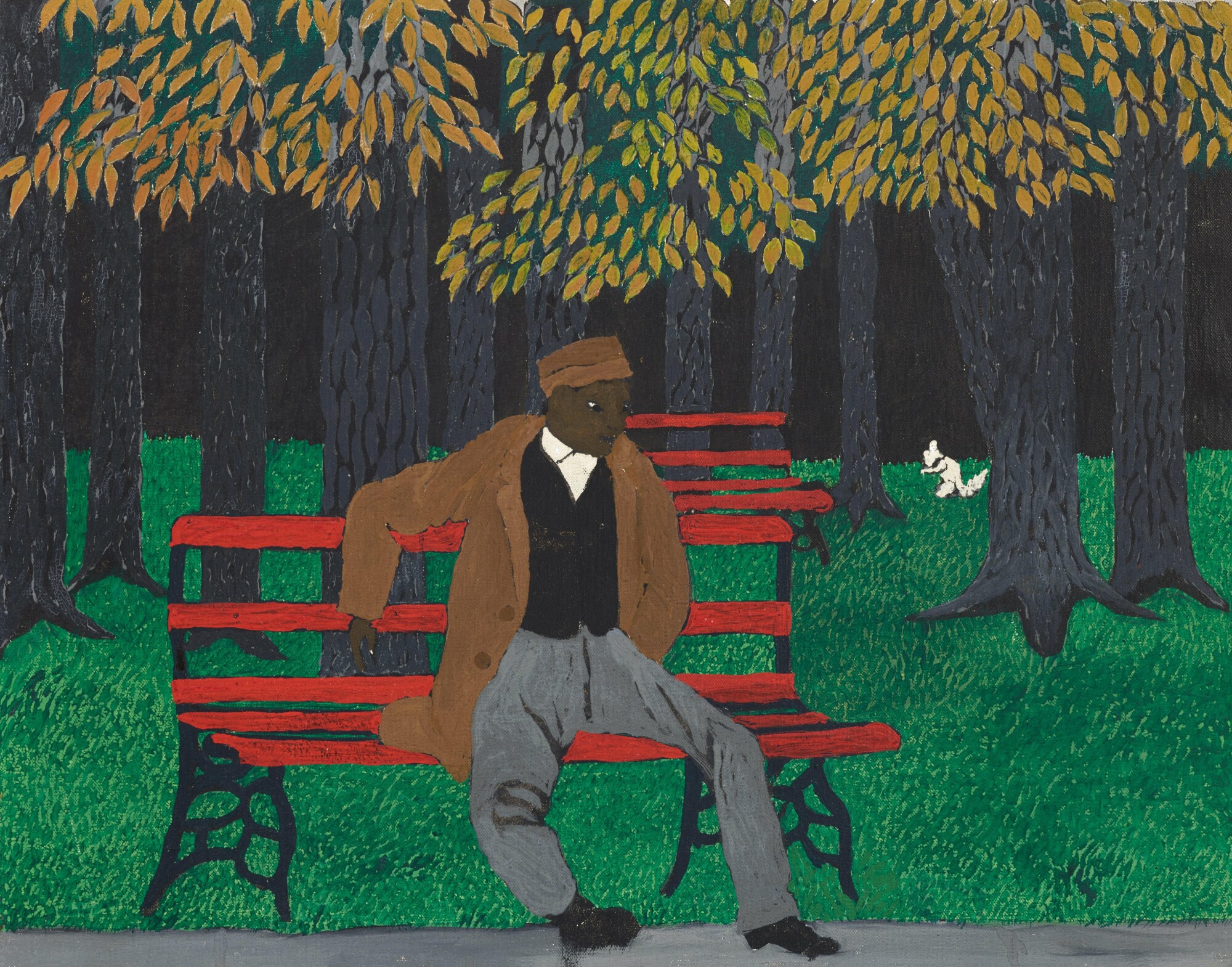

The Park Bench (1946) was one of Pippin’s last completed paintings (Fig. 4).

FIGURE 4: Horace Pippin, The Park Bench, c. 1946, oil on canvas, 33 x 45.7 cm. (Image courtesy of The Philadelphia Museum of Art.)

Here we see an older black man sitting on a park bench with trees, animals, and natural scenery.11 The painting may have been inspired by Pippin’s observations of a resident who liked to sit at a park near his home in West Chester, Pennsylvania, where he spent most of his life. One might imagine that this painting, done near the end of his life, reflects Pippin himself as the subject. He sits alone on the bench as he thinks about his challenging life, overcoming many struggles through his drive, perseverance, and hard work.

But most of all, Pippin used art as a form of rehabilitation—for the physical and mental-health injuries of war, and as a format/platform to process and work through the social problems of racism and poverty in America. Ultimately, a feeling of tranquility and contentment emanates from this painting, perhaps showing his state of mind toward the end of his life. The Park Bench depicts an elegantly-dressed older man who sits somewhat awkwardly with one arm pushing back on the bench supporting his back and his right leg and foot turned inward in an uncomfortable manner. And yet, he seems fulfilled and at peace in this painting, a final testimony to his faith in art as a tool for rehabilitation and social change.

Member since 2019 | JM14274

Member since 2019 | JM14274

NO COMMENT