Viral Imaginations: Healing Through Pandemic Narratives

By Michele Mekel, JD, MHA, MBA; and Lauren Stetz, PhD Candidate, MA

Abstract

Preserving and documenting the lived, pandemic experiences of Pennsylvanians through visual art and creative writing, the Viral Imaginations: COVID-19 project functions as both a historic archive and a reflective, healing resource. Linking the fields of art, health humanities, and bioethics, this interdisciplinary endeavor offers a template for artistic introspection and expression as a method for coping with individual and collective trauma. In so doing, Viral Imaginations overcomes narrative privilege by collecting pandemic stories across diverse intersectionalities.

There is magic in hearing a story and taking what medicine you need from it …

— Maria DeBlassie1

In March 2020, we awoke to the dystopian reality that COVID-19 had become a global pandemic. Our lived experiences had not prepared us for the stresses, strains, and losses of this new reality that began with an extended shelter-in-place phase, which promised—but failed—to curtail the invisible, virulent enemy we did not understand. Life as we knew it dramatically mutated into something unrecognizable and unwelcome—drastically altering how we worked, learned, socialized, provisioned, and grieved.

Yet, despite the shared experience of living under COVID-19, we have each uniquely endured and adapted during days, weeks, months, and now years, as the virus morphs and the pandemic enters new phases. Every pandemic narrative is important, and the telling and witnessing of individual stories serves both therapeutic and humanistic goals of healing and enhancing empathy. The conveying and contextualizing of such narratives are possible through the arts and the humanities, which play varied and important roles in daily life—ranging from expressing shared experiences to contributing meaning to those experiences.2 The arts and the humanities enhance human flourishing;2 part and parcel of human flourishing is the experiencing of wellbeing and the development of compassion for, empathy with, and caring about, others. These goals also reside at the heart of the health humanities, which aid in examining, understanding, coping with, and possibly improving the human condition.

This article details the development of the Viral Imaginations: COVID-19 project, an arts and health humanities endeavor that has attempted to capture vital narratives from across the spectrum of lived experiences during pandemic times. Tackling the exclusionary narrative privilege problem prevalent in the arts, the humanities, and history, Viral Imaginations features creative stories by those traditionally excluded. Moreover, the article provides insights into how similar endeavors would benefit healthcare, including rehabilitation, by creating understanding among and between patients, providers, and others involved in the circle of care.

Viral Imaginations: COVID-19: History and Purposes

In service to health and humanitarian goals, an interdisciplinary team at The Pennsylvania State University (Penn State) developed the Viral Imaginations: COVID-19 project (viralimaginations.psu.edu). The project strengthened our understanding of pandemic experiences and the ethical issues they raise, as well as established a just-in-time community resource for creatively coping. Launched during April 2020, amid the pandemic’s shelter-in-place phase, Viral Imaginations3 took the form of a publicly-accessible, web-based archive of creative writing and visual art (Fig. 1). To date, Viral Imaginations boasts nearly 350 works by approximately 250 contributors and has attracted more than 15,000 site visits.

Altering Narrative Privilege

Using a health humanities orientation, Viral Imaginations attempted to mitigate the persistent problem of narrative privilege, in which society’s gatekeepers determine what narratives are collected and how they are valued.4 Narrative privilege, or the ability to tell stories through text or pictorial images, has traditionally belonged to the dominant genders, races, ethnicities, and classes, leaving many voices unheard and images unseen. In an effort to minimize gatekeeping, Viral Imaginations gathered creative narratives from Pennsylvanians of all ages, abilities, races, ethnicities, genders, orientations, and locations throughout the state. There are also submissions in a variety of languages other than English, including Spanish and Ukrainian. Maintaining equality across works, submissions were curated into either the visual art or the creative writing gallery by date.

The Artists: Creations From the Heart

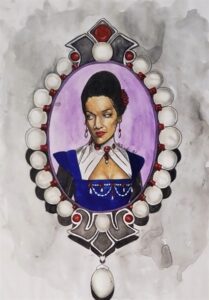

Shattering narrative privilege, artist Erika Richards “paints the majesty of Black people penetrating the world…beyond class, race, and culture” as “a reminder…that Black people’s existence surpasses the American History story.”5 In her work, “Pearl Cameo,” in the Viral Imaginations archive, Richards6 depicted a woman within an oval brooch (Fig. 2). Richards created this watercolor as a distraction while recovering from COVID-19 and simultaneously caring for her mother, who was also ill with the virus. Richards explained that as her mother’s illness worsened, she needed to create art to take up “space in [her] head so that [she] would not think worrisome thoughts.”6 Richards described the experience of shedding tears while painting and expressed relief that they did not ruin her watercolor.

In response to the Black Lives Matter (BLM) protests in the summer of 2020, many submitters addressed racial injustice, documenting travesties such as George Floyd’s murder by police. Through their visual reflections, they noted social divisions, highlighting exacerbated racial tensions alongside the pandemic. Calling for connectivity and racial healing, Jenna Deal’s (2021) sculpture,7 “Things We Take for Granted,” featured hugging black and white figures, stressing the importance of the BLM movement (Fig. 3).

Figure 3: Deal, Jenna. (2021). Things We Take for Granted. [Wood, Exterior Paint]. Courtesy of Jenna Deal.

Challenging the Art Historical Canon: Outsider Art

Based on elite group preferences, art and cultural canons often reflect the vision of scholars and critics who “embrace” and subsequently “deify” specific artworks.8(p1) The National Gallery of Art defines the art historical canon as a “conventional timeline of artists who are sometimes considered as ‘Old Masters’ or ‘Great Artists.’”9 According to aesthetic philosopher Paul Crowther, “art and the aesthetic are concepts of [W]estern origin.”10 (p55) Although the arts are clearly not exclusive to the West, scholars have traditionally evaluated art forms based on deeply rooted Euro-centric ideologies of worth and value. The vast majority of work within the artistic canon excludes creations by “women,” “non-[W]estern racial groups,” and non-heterosexual individuals, who represent the marginalized and have, as a result, frequently been denied entry to the canon.10 (p58)

Although “canon-making,” according to culture critic Wesley Morris, is an innately human desire, it faces push-back when confronted by the reality of lived experiences that differ from canonical representations.8(p1) Thus, historians look to outsider artists, unburdened by the constraints of the high-art world, for documentation of experiences outside the hegemony. “Disenfranchised from the art world,”11(p250) outsider artists can challenge high culture in ways that those from within frequently cannot. For example, the bold and visually striking work of artist Keith Haring12 exemplifies an outsider narrative of marginalized personal experience—that of a gay, HIV-positive man—to illuminate the lived realities of the American AIDS epidemic during the 1980s and 1990s. Haring provided others with an opportunity to witness his reality through bold colors, basic figures, and clearly communicated messages. Particularly, Haring’s work brought attention to HIV/AIDS and homosexuality in an era of public fear and HIV/AIDS stigmatization.13

Collecting and archiving artworks by diverse creators, many of whom are art-community outsiders, Viral Imaginations preserves authentic memories and concurrent feelings of living though the COVID-19 pandemic. Like Haring’s work, the pieces in the archive provide access to experiences that often occurred below the radar of the public eye, offering a robust perspective of life during pandemic times.

An At-Home Perspective

Created while she was in second grade, virtual learner Zoya Baloch’s “Fun Home,”14 provides a child’s perspective of pandemic life, amid the dysregulation of routines like in-person education and playdates (Fig. 4). While many parents endured stress and anxiety during the pandemic due to juggling working from home alongside their children’s remote schooling, Baloch’s mixed-media map of her home is joyful and refreshing. “I used bright colors because it reminds me of a rainbow,” explained Baloch.14 Chaotic and disjointed, the artwork utilized multiple perspectives. Baloch described her imaginary home as “a little more creative” than her actual home, depicting haphazard sleeping arrangements and a rooftop shower.14

Narrative Ethics: Making History One Story at a Time

The human endeavor of expressing our experiences and engaging with the experiences of others often takes the form of storytelling. Stories convey factual information and emotional content within a context-rich, narrative structure that allows for both self-understanding and meaningful knowledge-sharing.15 “Narratives are interpretive practices through which we make sense of our lives, and these meaning-making practices are ethically charged.”16(p3) Narratives uncover critical ethical insights that cultivate:

“…the key to a self-examined, responsible life; …an ethical relationship to the other; …a means of sharing experiences in ways that contribute to a sense of connection and community; …[the] develop[ment of] capacity for empathetic perspective-taking; and …a form of moral education [that] cultivates our moral powers.”16(p90)

As such, narratives play a crucial role in the arts, the humanities, and bioethics. Specifically, narrative ethics—while claiming no unified methodology—involves the sharing, witnessing, and examination of an individual’s identity-based, lived experiences.17 The purpose of this undertaking is to create an inclusive moral discourse in which voice, perspective, positionality, and personal background matter.17 The uniqueness of the teller’s story and the way it is told, including the language used, carry weight equal to what is told.18 Such narratives may be captured via numerous media, including creative writing and visual art, as in the Viral Imaginations archive.

Creative Writings, Tough Times

On par with Viral Imaginations’ visual art narratives, the archived creative writings capture personal stories from difficult times. David Martin’s19 poem, “Pandemic: Year Two,” shared both factual information about the pandemic and emotional reactions to it, while exploring community, divergent perspectives, and determining what conduct is ethically called for under the circumstances. He wrote:

I thought it would be done by now.

History and scientific wisdom belied my hopes

But I wanted to believe.

Surely we would mask.

Surely we would stay apart.

Surely we would listen.

Friends argued against shutdowns.

(They still do.)

People who’d never heard of hydroxychloroquine

Knew it would turn the tide.

It didn’t.

Half a million Americans aren’t wrong.

As they lie in judgment of those still living.

And here we are

Some of us still masked

Some of us still separate

Some of us listening

Some of us vaccinated

But none of us free

As a second year begins.19

Magnifying the value of such individual narratives, Viral Imaginations also features ekphrastic dialogues between submissions, as submitters found resonance in each other’s stories. Liv Taylor20 connected with Allie Lunger’s21 pencil drawing of a fractured face reflected in a cracked mirror (Fig. 5).

Figure 5: Lunger, Allie. (2021). Many Faces of Mental Health. [Pencil and Paint]. Courtesy of Allie Lunger.

I just don’t recognize her anymore.

She’s right there. Right in front of me.

But the longer I stare, the more I see a stranger. And it scares me. I can feel it in my stomach. Is that what I feel in my veins? Racing through my body?

She’s nostalgic. A stranger I know too well. But no one knows her like I do. Her strengths, her flaws, her habits. No one knows. But me. She’s a stranger, but she’s my best friend.

People think cracks are messy, but she knows better. I know better. Scars are not wounds; they are roots and proof of trials and tribulations. Flowers grow from dirt, so why can’t I? I love my roots. Cracks and all. So why do they scare me?

I know why. Too many cracks, and a mirror breaks. Good thing it’s just a reflection. Because the cracks in my body, in my roots, they’re not glass, they’re roots, and if we know anything about the earth, it’s that roots are strong, and grow from dirt, just like me.

And what’s more beautiful than that?20

Indeed, living in pandemic times has left cracks in our mental health, our routines, and our entire way of being in the world. Capturing the spirit of the Viral Imaginations project, as well as the ethical underpinnings of narrative ethics, Taylor’s20 ekphrastic piece demonstrates how stories told through artistic media help us interpret and embrace our experiences, heal through creative endeavors, and empathetically relate to the plights of others.

Viral Imaginations as Translational Template

The concept underlying the Viral Imaginations gallery and archive could easily translate as a powerful model for healthcare in virtually any specialty. A similar effort could be established either as a publicly-accessible Internet presence, like Viral Imaginations, or as a private intranet platform, featuring artistic expressions by patients, providers, and even nonprofessional caregivers and family members. Such a venue would allow for the sharing of lived experiences addressing illness, disability, recovery, caretaking, and/or loss. Contributions could be cordoned off into galleries dedicated to specific media or separated by contributor identification. As with Viral Imaginations, submissions could include creator name or be anonymized, at the submitter’s option.

Engagement with narratives within contributor-identification groups (ie, patient, caregiver, provider, etc.) would establish a semblance of community, providing patients and their loved ones with a sense of solidarity during arduous, and often confusing, times. Perhaps, even more importantly, engagement with creative narratives across contributor-identification groups could enhance understanding, empathy, and co-created problem-solving by better equipping all parties, especially patients and providers, to engage in more productive ways.

Moreover, a Viral Imaginations-like project could serve as an effective teaching tool for understanding the patient experience and developing enhanced empathy. “[C]ombining narrative pedagogical techniques and visual art can be applied to …diseases, conditions, and epidemics and has been employed in instruction in health care.”22(p 12),23 Creative works can be used to aid health-profession students in recognizing that illness, disease, and disability are as much sociocultural issues as they are medical concerns.22 In similar ways, Viral Imaginations has served as a hands-on learning laboratory steeped in the health humanities for Penn State students across numerous disciplines.

Conclusion

The Viral Imaginations project provided Pennsylvanians with a creative outlet for sharing their pandemic experiences and developing a sense of community. By offering this resource the project brought to life the value of the arts and the humanities in critically addressing crises. Functioning as a creative archive of first-person narratives across diverse intersectionalities, Viral Imaginations preserves for future study self-represented stories of life in pandemic times. Additionally, Viral Imaginations offers up a robust and easily transferrable platform applicable to numerous topical applications within—and beyond—healthcare.

Acknowledgements

The authors extend gratitude to Viral Imaginations: COVID-19 intern Grace Joseph for her research assistance.

References

- DeBlassie M. Practically Pagan: An Alternative Guide to Magical Living. Blue Ridge, PA: Moon Books; 2021.

- Shim Y, Jebb AT, Pawleski JO. Arts and humanities interventions for flourishing in healthy adults: a mixed studies systemic review. Rev Gen Psychol. 2021;25(3):258-282. https://doi.org/0.1177/10892680211021350. Accessed December 20, 2021.

- Viral Imaginations: COVID-19 website. https://viralimaginations.psu.edu. Accessed December 20, 2021.

- Adams TE. A review of narrative ethics. Qual Inq. 2008;14(2):175-194. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800407304417. Accessed December 20, 2021.

- Richards E. Erika L. Illustrations website. https://www.erikarichards.com. Accessed December 20, 2021.

- Richards E. Pearl Cameo. Viral Imaginations: COVID-19 website. https://viralimaginations.psu.edu/visual-submissions/pearl-cameo/. Published June 12, 2021. Accessed December 20, 2021.

- Deal J. Things We Take for Granted. Viral Imaginations: COVID-19 website. https://viralimaginations.psu.edu/visual-submissions/things-we-take-for-granted/. Published January 14, 2021. Accessed December 20, 2021.

- Morris W. Who gets to decide what belongs in the ‘canon’?. New York Times. May 30, 2018:11. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/05/30/magazine/who-gets-to-decide-what-belongs-in-the-canon.html. Accessed December 20, 2021.

- Canon of art history. National Gallery of Art website. https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk /paintings/glossary/canon-of-art-history. Accessed December 20, 2021.

- Crowther P. Defining Art, Creating the Canon: Artistic Value in an Era of Doubt. Oxford: Clarendon; 2007.

- Prinz J. Against outsider art. J Soc Philos. 2017;48(3): 250-272. https://www.doi.org/10.1111/josp.12190. Accessed December 20, 2021.

- The Keith Haring Foundation website. https://haring.com. Accessed December 20, 2021.

- Stewart J. 7 Facts About Pioneering Street Artist Keith Haring. My Modern Met. https://mymodernmet.com/keith-haring/ . Published February 17, 2020. Accessed December 20, 2021.

- Baloch Z. Fun Home. Viral Imaginations: COVID-19 website. https://viralimaginations.psu.edu/visual-submissions/1625/. Published October 17, 2020. Accessed December 20, 2021.

- Serrat O. Asian Development Bank website. https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/27637/storytelling.pdf. Published October 2008. Accessed December 20, 2021.

- Meretoja H. The Ethics of Storytelling; Narrative Hermeneutics, History, and the Possible. Oxford; Oxford University Press: 2017.

- Gotlib A. Feminist ethics and narrative ethics. Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy website. https://iep.utm.edu/fem-e-n/. Accessed December 20, 2021.

- Zaharias G. What is narrative medicine. Can Fam Physician. 2018;64(3):176-181.

- Martin D. Pandemic: Year Two. Viral Imaginations: COVID-19 website. https://viralimaginations.psu.edu/written-submissions/pandemic-year-two/. Published April 25, 2021. Accessed December 20, 2021.

- Taylor L. A response to Allie Lunger’s “Many Faces of Mental Health.” Viral Imaginations: COVID-19 website. https://viralimaginations.psu.edu/written-submissions/a-response-to-allie-lungers-many-faces-of-mental-health/. Published November 29, 2021. Accessed December 20, 2021.

- Lunger, A. Many Faces of Mental Health. Viral Imaginations: COVID-19 website. https://viralimaginations.psu.edu/visual-submissions/many-faces-of-mental-health/. Published February 4, 2021. Accessed December 20, 2021.

- Smith JA. Keith Haring, Felix Gonzalez-Torres, Wolfgang Tillmans, and the AIDS epidemic: the use of visual art in a health humanities course. J Med Humanit. 2019;40(2): 181-198. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10912-018-9506-4. Accessed December 20, 2021.

- Freeman LH, Bays C. Using literature and the arts to teach nursing. Int J Nurs Educ Scholarsh. 2007;4(1): 15. https://doi.org/10.2202/1548-923X.1377. Accessed December 20, 2021.

Member since 2019 | JM14274

Member since 2019 | JM14274

NO COMMENT