Piloting a Photography Program as Recreational Therapy for Adults With Spinal Cord Injury

Table of Contents

In recent decades, the Western concept of health has evolved past a strictly biomedical model to one that encompasses the entire person. While physical survival might be our most basic need, it alone is not enough to sustain us. The desire to engage, to connect, to live meaningfully, and to create is embedded deep within the human psyche. Therefore, the journey to health also needs to address wellness of mind, heart, and spirit.

Therapeutic recreation is an effective modality for use in physical and psychological recovery. Meaningful leisure activity (ie, activities that require the exertion of mental and/or physical energy) has been shown to be especially important, with the opportunity for individuals to proactively lead the process of engagement.1-2 For adults with spinal cord injury (SCI), participation in active leisure is associated with improved quality of life.3-5

In a thematic analysis of leisure experiences for adults with SCI, Chun and Lee1 found that meaningful engagement in such activities contributes to positive personal transformation in the following ways:

- Providing opportunities to discover unique abilities and hidden potential

- Building companionship and meaningful relationships

- Making sense of traumatic experiences and finding meaning in everyday life

- Generating positive emotions

Compared to able-bodied individuals, however, adults with SCI spend more time in passive leisure such as watching television, which is a less satisfying domain of activity than active leisure.6-8

Virtual art production, which includes photography, is an engaging, meaningful activity known to contribute to physiological and psychological resilience through increased brain function connectivity and reduced stress hormone levels.9-10 To the authors’ knowledge, education in the art of photography has not been previously introduced by rehabilitation centers as therapeutic recreation for adults with SCI.

Creative Photography for Adults With SCI

This article describes the development of a pilot program of educational courses in photographic arts for adults with SCI. Outcomes from the pilot, including correlation with the qualitative themes described by Chun and Lee,1 will also be discussed. (Note: All photographs appearing in this article were taken by graduates of the program.)

Figure 1: Under the City (Photograph by Daniel Alvarez.)

Institutional Context

Rancho Los Amigos National Rehabilitation Center (RLANRC; Rancho in this article), consisting of a Los Angeles County public hospital and associated clinics, provides high-quality, comprehensive care for people with disabilities. The hospital admits 4,000 inpatients, and the clinics conduct 78,000 outpatient visits annually. It is accredited by both the Joint Commission and the Commission on Accreditation of Rehabilitation Facilities (CARF), and has been designated as a Center of Excellence for SCI.

Rancho is also recognized as a leader in the application of world-class neuroscience and neurorehabilitation, and is one of only 14 SCI Model Systems in the United States. Rancho Research Institute (RRI) was established in 1956 to oversee and administer Rancho’s medical research. RRI also offers comprehensive community-based educational programs such as Therapeutic Gardening, Return to Driving, Managing Life With Aphasia, Living Life Poststroke, and psychosocial support programs for people with neurologic disabilities and their families and caregivers. A variety of adaptive fitness classes include Pilates, yoga, Tai Chi, balance/vestibular training, cardio-pump, Zumba, wheelchair sports training and competition, and outside programs such as rock climbing, skiing, and various water sports.

Rancho has been designated as the Patient-Centered Medical Home for SCI in Los Angeles County, providing services to its large, often underserved, population. Approximately 1,900 individuals with SCI are seen at Rancho and RRI annually. Compared to other rehabilitation facilities in the U.S., adults with SCI using the Rancho outpatient services are predominantly Hispanic (68%), have a higher level of disability, and tend to come from economically disadvantaged backgrounds, with 49% covered by Medicaid in 2018.

Program Development

Many Rancho adult outpatients who use a wheelchair also experience poverty and reside in disadvantaged communities where a high incidence of violence occurs. For example, 66% of the students in the first year of the pilot program had been shot or stabbed.11 Financial stress, transportation barriers, and other challenges may preclude them from having the time or resources to experience the full benefits of outpatient therapy.

The intention behind the photography pilot was to create an art program with these individuals and their circumstances in mind. Frequently underserved, this group is an important population for rehabilitation programs to include, especially those studying ways to reduce activity limitations and improve quality of life.

Digital Photography as Creative Outreach

Although Rancho has a long history of providing art education to individuals undergoing rehabilitation, its painting classes are conducted primarily for the pediatric population, ages 14 and younger. In considering how to best adopt such a program for an adolescent and adult population, the project developers decided that digital photography might be a more inclusive creative endeavor as it does not presuppose artistic talent.

Accordingly, the team lead created a proof-of-concept project that was funded by the Los Angeles County Supervisors’ office and Rancho. The four-month program was administered by RRI in 2007 and included six adults over 18 with SCI.

Professional photographer Michael Ziegler was chosen as the instructor, and later, as leader of the pilot program series. Ziegler has 36 years of experience in commercial photography; sports photography; stock photography; and fine art photography, including black-and-white street scenes, landscapes, children, energetic motion studies, abstract shapes and colors, still life, and architecture.

After the successful completion of the proof-of-concept project, the RRI pilot program entitled “Photography as Therapy for Individuals with Spinal Cord Injury” was funded by three Quality of Life project grants (the Craig H. Neilson Foundation in 2014 and 2016, and the Christopher and Dana Reeve Foundation in 2017.) In each of the three program years, adults with SCI were recruited from the Rancho outpatient SCI clinic, SCI support groups, and the community, and asked to enroll in a five-month course.

Figure 2: Tractor Fair (Photograph by William Herrera.)

Description of the Pilot Program

Student Demographics and Course Retention. A majority of the students were male (80%), of Hispanic/Latino origin (64%), and had thoracic spinal injuries. Age range was 22 to 47 years and 40% had some previous experience with art, design, media, or photography. Table 1 shows enrollment numbers across the duration of the pilot program and shows course retention for study participants.

Table 1: Photography Course Enrollment and Completion

| Unique Individuals | 2014 | 2016 | 2017 |

| Enrolled in courses | 18 | 14 | 15 |

| Completed courses | 13 | 12 | 12 |

| Retention rate | 72.2 | 85.7 | 80.0 |

| New students | 18 | 8 | 6 |

| Continuing students | — | 4 | 6 |

Course Overview. Digital cameras were provided for use in home and community environments. By the third year, equipment was upgraded from compact cameras to digital single-lens-reflex cameras (e.g. Canon EOS). Students were allowed to keep their cameras upon completion of the course.

Instruction included an introduction to a range of photography genres, training strategies in the use of digital cameras, and practice with the Adobe Photoshop Elements imaging software program that allowed editing and production of exhibit-quality prints.

Weekly homework was assigned and students were encouraged to maintain a personal journal for the purpose of creating photograph captions and artistic statements for exhibitions.

Over each five-month course, students progressed from beginner to intermediate, and, finally, to an advanced level. Upon completion, each student produced up to 10 finished photographs to be framed and showcased in a program-specific exhibition at Rancho attended by their peers, hospital staff, and members of the community.

Special Activities. As the program grew, special activities were created to support the insights and talents of the attending students.

Field trips. To provide more opportunities to take photographs in community settings, the program included field trips to such locations as a Japanese garden, Venice Beach, Chinatown, the Getty Museum, Santee Alley, and the downtown Los Angeles Arts District. During some outings, the students shared meals in restaurants, which helped foster their growing camaraderie.

Guest speakers. Each semester, several professional photographers from the region gave pro-bono presentations offering various perspectives and genres of photography to broaden students’ exposure to artistic approaches and interpretations. Speakers included:

- John Free: World-renowned street photographer and social documentarian who has taught classes at USC, UCLA, and the L.A. County Museum of Art. See his involvement at this YouTube link.

- Rafael Gardenas: Self-taught photographer who captures moments of vulnerability in portraits, landscapes, and architecture, allowing him to explore his relationship with the streets of East Los Angeles. Gardenas has been featured in the Los Angeles Times and has released a book of his photography.

- Deb Halberstadt: Former manager of NBC’s Media Services-Photography for Corporate Communications. She has worked for the Associated Press as a picture editor and photographer.

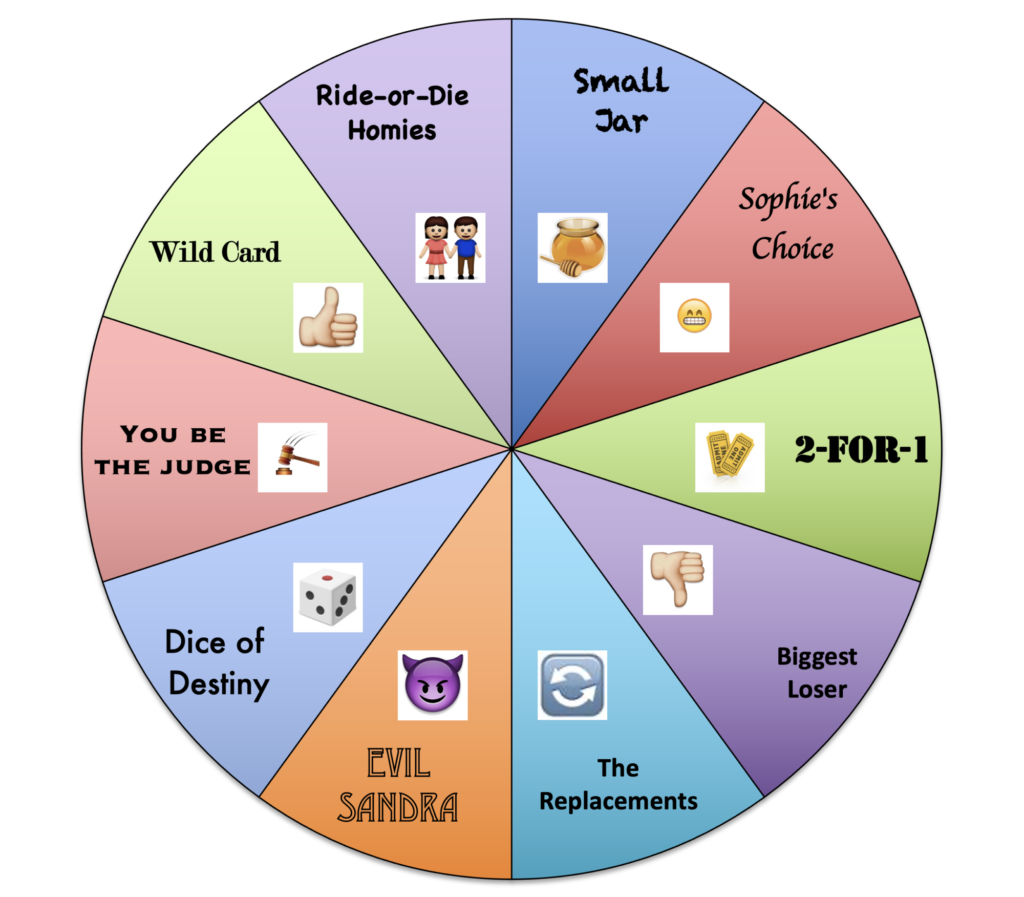

Wheel of Mayhem Game. To help promote student engagement and participation, the project coordinators created an innovative game. Whenever students completed their photography homework, presented a journal entry, offered a thoughtful critique of another student’s work, mentored another student to develop their skills, or were awarded the best photo of the week, a ticket with their name was deposited in a jar. The more activities that were completed, the more tickets were placed in the jar for a chance to win a camera at the end of the course. Additionally, at the beginning of each class, the instructor would pull a ticket from the jar and the chosen student would spin a roulette wheel. Depending on where the arrow landed, the student could win or lose tickets (Addendums 1-2.) This game proved quite motivational and popular with students.

Evolution of the Program

Based on the experiences and feedback from the first year of the pilot, the following changes were made:

Class Frequency. The original intention was to hold a four-hour class once a week. However, because of space limitations, the class was instead divided into two three-hour sessions, which had the added benefit of greater one-on-one time with the instructor.

Transportation. Attrition due to limited transportation options for people with physical disabilities proved to be an important factor in the first year of the project (Table 1.) By the third program year, the following services were included in the budget:

- A chartered bus for field trips

- Travel stipends for students who were able to provide their own transportation

- Special-purpose, free transportation for those students who could not provide their own transportation

Student Requests for Additional Content. After the first year, several graduates expressed interest in taking additional courses in self-leadership, peer mentorship, and career development so that they might pursue a career in photography. These components were incorporated into later program years via guest speakers and the introduction of teaching assistants.

Teaching Assistants. Two photography program graduates joined the 2016 and 2017 programs as paid teaching assistants. They added several important benefits to the class:

- Providing a level of education, support, mentorship, and skilled resources that only fellow peers can offer

- Creating a video with the students to document their experiences

- Using the program’s social media sites to raise awareness about the RRI photography program, network, and collaborate with community resources

- Inspiring both beginner and advanced students to further explore photography and other forms of art as therapeutic recreation and possible employment

- Serving as guest speakers after having gone on themselves to pursue opportunities in photography, video, and art

From the authors’ perspective, the introduction of the teaching assistants considerably improved the learning experience and confidence reported by students of both years. Indeed, recent research shows that receiving peer support promotes participation and life satisfaction for adults with SCI.12

Outcomes

Creative Productions

Photography Exhibitions. At the end of each semester, selected photographs were displayed for sale at a public exhibition at Rancho. The students’ photographs were frequently poignant and thought-provoking. Craftsmanship was also apparent with aesthetic richness and the technical control of light and exposure.

Figure 3: Big City Dreamer (Photograph by Jerry O’Brien.)

Student Recognition. Positive community response resulted in many students being recognized for their work. At the 2014 exhibition, $1,000 worth of photographs were sold; in 2016, $1500; and in 2017, $540 in a single exhibition. All the proceeds went directly to the students, offering realistic validation of a possible new career goal. The course evaluations showed that the students appreciated having the opportunity to display their work in a photography exhibition.

In 2015, several graduates also exhibited photographs at the Annual Art Show at the Aquarium of the Pacific in Long Beach, California.

Exhibition Catalogues and Photography Books. Exhibition catalogues and high-quality hardcover photography books were produced for both the 2014 and 2016 program years. With the inclusion of biographical statements, these served as a personal portfolio for students.

Web Gallery. The project coordinator updated and maintained the RRI web gallery (https://www.ranchopix.com)for one year following each pilot program. The gallery featured biographies of the students and an online portfolio of their work.

Qualitative Themes

Upon graduation, students were asked to give feedback on the program. In addition, students in the 2017 program took part in a video interview. Their responses were consistent with the areas of positive transformation identified in the paper by Chun and Lee1 and are categorized below:

Theme #1: Opportunities to discover abilities and hidden potential

“One thing that I’ve learned about myself through this course is that I have a natural eye for photography. The first really good picture I got was a week into the class. It’s actually the picture that’s on the cover of our class photography book.” –Daniel Alvarez.

Figure 4: Stairway to Heaven (Photo by Hobal Grajeda.)

“I love that photography is something I can do by myself. It gives me a sense of accomplishment and improves my self-esteem. Photography has changed the way I see the world and through my photographs, I show others how I experience the world.” –Hobal Grajeda

Theme #2: Making sense of traumatic experiences and finding meaning in everyday life

“The class has encouraged me to see what life is really about. Instead of staying home and feeling sorry for myself, I go out with my camera and shoot interesting things. I’m meeting more people, and I’m experiencing things I wouldn’t have experienced before. I’m enjoying life now. I feel much more confident and very independent.” –Michael Lopez

“The photography course has taken my disability away because I’ve been out more. It just kind of opened my eyes to a whole new world of things to do.” —Daniel Alvarez

Theme #3: Generating positive emotions

“I have gotten used to being in chronic back pain daily but getting out to do photography really helps me push myself to do more, and my clinical depression gets better when I’m involved in the program.” –Jerry O’Brien

“I feel more independent since taking this course just because it’s taken me out of my house more and I’m doing a lot more. And it’s really helped me a lot. I find myself in the street a lot more during the week that otherwise I would spend at home.” –Daniel Alvarez

Other positive emotions mentioned by students included increased relaxation, pride and a sense of accomplishment, more confidence, and feeling empowered through learning a new skill.

Theme #4: Building companionship and meaningful relationships

“The encouragement that I’ve gotten from the instructor, Michael, and from my classmates has helped to open my eyes to a whole new world of possibilities.” –Daniel Alvarez

The project coordinators and staff observed strong friendships forming among individuals who might never have met under other circumstances. Students supported each other throughout the course, offering constructive critiques and assistance. Several even created their own assignments wherein they scheduled days to meet and photograph each other’s hometown. These emotional connections continued even after completion of the course. Graduates regularly shared information on new techniques and better photographic practices. Some showed their work in other venues and these events were well-attended by their classmates. The relationships these students established were not just defined by photography but expended past the classroom environment and into the realm of true, long-term friendships.

Although the effectiveness of a program is usually considered in terms of population groups, aggregate measures cannot fully convey the impact on individual participants. To help illustrate the latter, the authors have included Melissa Allensworth’s story. Her words paint a compelling picture of the photography pilot from a personal perspective.

Melissa’s Story

Melissa Allensworth was only 27 years old when she suffered a complete T4 spinal cord injury after a rollover car accident in 2008. Despite the new challenges she faced, Melissa was determined to continue living her life to the fullest. “I made it a goal early on that I wouldn’t let my injury hold me back from experiencing fun and adventure,” she says. “Once I made that decision, doors started opening. I just try to take advantage of every opportunity that’s out there.”

For Melissa, those words are not just sentiment but a way of life. Since her accident, Melissa has traveled internationally, and road-tripped across the United States. She paddleboards, handcycles, scuba dives, and takes part in the biannual wheelchair sports festival. One of her proudest accomplishments is the pilot’s license she earned through Able Flight, an intense seven-week program that teaches individuals with disabilities how to fly airplanes. Melissa also volunteers as an outreach representative for the Triumph Foundation, a non-profit organization that provides hope and resources to individuals with SCI. “It’s been really fulfilling to be connected with this program, to give back and let people know that’s there’s still life after disability,” she says.

But it is Melissa’s creativity that has, like a siren’s song, irresistibly beckoned to her throughout the years. Early on, she had planned a career in film making and graduated from the Art Institute of Los Angeles with a degree in video production. Melissa later realized, however, that she had her own creative vision and was not happy making other people’s movies. After her injury, she instead began painting and was awarded an artist residency at the Vermont Studio Center. Melissa subsequently became a professional artist, exhibiting her work in gallery showings and on her website.

Despite these accomplishments, there was one door Melissa believed to be permanently closed. “After I was injured, I thought, ‘Oh my gosh, I can’t take photos again because I’m sitting in a wheelchair. I only have this one angle now. I can’t see things,’ ” she says. Melissa just assumed her photography days were behind her.

Once Melissa enrolled in the photography pilot program, however, she realized her beliefs had been holding her back from her true potential. “My view of my injury and myself was limiting,” she says. “The class helped expand that. It completely changed my perspective and point of view. You’re just limited by your mind. I saw I could do more than what I thought I could.”

After gaining confidence through seeing the public appreciate and buy her creations, Melissa has now added photography to her artistic repertoire. “It’s all about how an image makes me feel. I take a photo of the feeling I’m trying to convey,” Melissa explains. “I do a lot of work in black and white because I think it adds emotion. Color can be distracting.”

Because the spinal cord injury community is small, she frequently sees previous classmates at events, gatherings, and on social media. Melissa has remained friends with many of them and knows they have also continued to take photographs, some professionally.

Figure 5: 25 Cent View (Photography by Melissa Allensworth.)

When asked about the class’s long-term impact, Melissa says, “It was definitely life-changing. I thought I’d never pick up a camera again. Now I’m exhibiting photographs and making works of art.”

Discussion

A fundamental goal of both the proof-of-concept and pilot projects was to provide a supportive educational environment so students could develop the necessary technical and artistic skills for creative self-expression. In the article entitled “Photography and Art Therapy: An Easy Partnership,” the author states that adults with SCI “may find meaning and cohesion in their life stories through individual artmaking with photographs.”13 And according to class instructor Michael Ziegler:

“Photography is an ideal tool to engage and inspire people who are struggling with their lives. Photography combines instant, tangible gratification with the potential to rework an image to perfection and then to share with friends and strangers to get important feedback, to provide reaction and emotion…by opening students’ minds to the possibility of the entire photographic process—technical skills, visualization, anticipation, artistic execution both in-camera and with the computer—we can change the focus of a troubled existence, one that might be only going through the motions of life. Students may see what they thought was an ordinary world in an entirely new way and discover the thrill of being able to capture that new vision and put it on paper or on a website to share with others.”

Although further studies would be needed to gauge the true long-term impact, it appears from the aforementioned outcomes, feedback from the students, and the program coordinators’ observations, that the pilot program met its goal. Through their artistic achievements, students gained confidence in their abilities. They began to see the world through new eyes. Many became friends, providing emotional and practical support for each other. They learned skills that could assist in future employment: Two graduates are now employed at Rancho and at least four have pursued photography professionally. This new perspective had a profound experience on the students captured in the following quotes from two of them:

“In five years from now, after taking this photography course, I see myself being an artist. Maybe doing photo shoots, maybe even having my own photo place. You know, taking pictures of people, doing weddings because there’s a lot to do with photography. And possibly even teaching others. I love to teach, especially children. I love working with children and teaching them things.” –Michael Lopez

“I am actually into video and my view through a camera has helped a lot. To have a good eye for locations, just how to place people in the frame can help me out a lot. One of the goals I have is making a documentary about living with spinal cord injury and its effect on people.” – Daniel Alvarez

For underserved populations, programs such as the photography pilot may offer opportunities and benefits otherwise not readily available to them. Photography may also give them a voice, a way to speak their truth to a society that only becomes stronger when all its members—especially those who have been historically underrepresented—are heard. Art can serve as a powerful medium to explore different cultures and life experiences while also uniting people in their shared humanity.

Figure 6: Unseen (Photograph by Jonathan Alvarenga.)

Conclusion

The outcomes of this pilot educational program suggest that recreational photography can be a powerful modality in the psychosocial wellbeing and ongoing rehabilitation of adults with SCI. In addition to the obvious social aspects, the authors observed an improvement of mood, development of artistic and technical skills, increased confidence, and excitement for the artistic process. Albert Bartee III, a student of the pilot program, summarizes this well in the following quote:

“It’s helping me to develop more patience, maintain my strength, as well as improve my communication skills, and even my people skills. During photography, you come across obstacles. When I’m shooting, I often ask myself, ‘What if?’ and thinking about difficulties as things that can be beautiful instead of obstacles has made me look at my life differently. That is something for which I am very grateful.” —Albert Bartee III

In many ways, the pilot helped bring together the students and the Rancho professional community. Students’ photographs can be found throughout the campus; the photography exhibitions have been well attended by staff, and graduates are frequently approached to serve as photographers for various Rancho-sponsored activities.

During the American Hospital Association’s 2011 roundtable on Workforce Roles in a Redesigned Primary Care Model, it was recommended that hospitals serve as catalysts for linking and integrating various components of health and wellness together for patients in a sustainable infrastructure.14 To that end, RRI is actively exploring new avenues to ensure the long-term success of the photography program. Plans for the next phase include online lectures by professional photographers, community-based Meetups, and biannual photography competitions. Any adult with disability in the Rancho community will be welcome to participate. The project coordinators also intend to seek out collaboration with other institutions to create a community of like-minded artists and rehabilitation providers.

The authors hope that the disseminated results of this pilot will lead to improvements in the approach of rehabilitation care and educational programs for adults with SCI. It could serve as a model for the incorporation of visual arts production during neurological rehabilitation in order to support meaningful engagement in recreational activities. The proliferation of similar programs could only improve the well-being and independent living of these individuals. Furthermore, photography as therapeutic recreation and art therapy could be offered to other populations of people living with chronic disabilities with possibly similar benefits.

Figure 7: The Dog (Photograph by Ramon Cervantes.)

The authors would like to extend special recognition to Charles A. Stewart, MD, for his encouragement, support, and steadfast advocacy of this program. The authors also thank Spencer Toledo, Sandra Avina, Sheetal Desai, MD, Linda Sutherland, and Stephanie Bughi for their invaluable contributions, as well as Ginte Jasulaitis, MD, and Stephen Arthur, MFA, MSc, for providing the writing and editing of the article.[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]

Funding

This project was supported in part by Grant Nos. 280512 and 361725 from the Craig H. Neilsen Foundation and Grant No. 90PR3002-02-01 from the Christopher and Dana Reeve Foundation.

References

1. Chun S, Lee Y. The role of leisure in the experience of posttraumatic growth for people with spinal cord injury. J Leisure Res. 2010;42(3):393-415. https://www.nrpa.org/globalassets/journals/jlr/2010/volume-42/jlr-volume-42-number-3-pp-393-415.pdf

2. Iwasaki Y. Leisure and meaning-making: implications for rehabilitation to encourage persons with disabilities. J Voc Rehabil. 2017;46:225-232.

3. McVeigh DA, Hitzig SL, Craven BC. Influence of sport participation on community integration and quality of life: a comparison between sport participants and non-sport participants with spinal cord injury. J Spinal Cord Med. 2009;32(2):115-124. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19569458

4. Kleiber DA, Brock SC, Lee Y, Dattillo J, Caldwell L. The relevance of leisure in an illness experience: realities of spinal cord injury. J Leisure Res. 1995;27(3):283-299. https://www.calvin.edu/~y133/documents/Relevanceofleisureinanillnessexp95.pdf

5. Boschen KA, Tonack M, Gargaro J. Long-term adjustment and community reintegration following spinal cord injury. Int J Rehabil Res. 2003;26(3):157-164. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14501566

6. Pentland W, Harvey AS, Smith T, Walker J. The impact of spinal cord injury on men’s time use. Spinal Cord. 1993;37(11):786-792. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10578250

7. Tasiemski T, Kennedy P, Gardner BP, Taylor N. The association of sports and physical recreation with life satisfaction in a community sample of people with spinal cord injuries. Neurorehabil. 2005;20(4):253-265. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16403994

8. Benony H, Daloz I, Bungener C, Chahraoui K, Frenay C, Auvin J. Emotional factors and subsequent quality of life in subjects with spinal cord injury. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2002;81(6):437-445. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12023601

9. Bolwerk A, Mack-Andrick J, Lang FR, Dorfler A, Maihofner C. How art changes your brain: differential effects of visual art production and cognitive art evaluation on functional brain connectivity. PLoS One. 2014;9(7):e101035. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24983951

10. LaVela SL, Balbale S, Hill JN. Experience and utility of using the participatory research method, photovoice, in individuals with spinal cord injury. Top Spinal Cord Inj Rehabil. 2018;24(4):295-305. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30459492

11. A Class Act: Photographs From the Students of Rancho’s Research Institute’s Inaugural Class (February-June 2014). Downey, CA: Rancho Research Institute; 2014. (Exhibition catalogue.)

12. Sweet SN, Noreau I, Leblond J, Martin Ginis KA. Peer support need fulfillment among adults with spinal cord injury: relationship with participation, life satisfaction, and individual characteristics. Disabil Rehabil. 2016;38(6):558-565. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26017541

13. Kopytin A. Photography and art therapy: an easy partnership. Inscape. 2004;9(2): 49-58.

14. Aquarium of the Pacific’s 12th Annual Festival of Human Abilities Features Performances and Free Art Classes for Everyone [press release]. Long Beach, CA: Aquarium of the Pacific; 2015.

15. Workforce Roles in a Redesigned Primary Care Model. American Hospital Association; 2011. http://www.aone.org./resources/primary-care-workforce-needs.pdf

Addendum 1: Roulette Wheel in Wheel of Mayhem Game

[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]Addendum 2: Explanation for Roulette Wheel in Wheel of Mayhem Game

[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]Addendum 2: Explanation for Roulette Wheel in Wheel of Mayhem Game

If you land on…

| …here’s what happens. |

| 2 – for – 1 | For every ticket you earn during this class, you get an additional ticket. Two for the price of one! |

| Biggest Loser | Lose 3 tickets. |

The Replacements | Take out 3 of someone else’s tickets (your choice!) and replace them with 3 of your own. |

You be the judge! | You’re the judge of today’s photo contest! You may award 2 tickets for first place, 1 ticket for second place. You are allowed to choose your own photo! |

Ride-or-Die Homies | Choose a friend. We’ll hold two cards behind our backs, one in each hand – an angel card and a devil card. You pick a hand. If you pick the angel card, you and your friend each win 2 tickets! If you pick the devil card, you both lose 2 tickets. |

Evil Sandra | Sandra chooses what happens here. She’ll either choose one of the existing scenarios or come up with one on the fly. You’d better be nice to Sandra lest she smite you a mighty blow! |

Dice of Destiny | Roll each of two colored dice. The darker die is the bad die, the lighter die is the good die. Whichever die has a higher number, you gain or lose that many tickets. |

| Sophie’s Choice | You have two choices: You can either a) take 3 additional tickets for yourself, OR b) remove 3 of someone else’s tickets. |

Small Jar | The small jar contains everyone’s name twice. Each name in the jar has either a thumbs up or thumbs down on it. We’ll pick one name out of the small jar, and depending on which ticket is picked, that person will either gain or lose 3 tickets. |

Wild Card | You get to pick any of the scenarios on the Wheel of Mayhem, OR you can choose to put your ticket back in the jar, OR you can try your luck at one of the mystery boxes. |

About the Author(s)

Yaga Szlachcic, MD

Yaga Szlachcic, MD graduated from medical school in Warsaw, Poland, and completed her post-graduate training in Canada and California. Highly regarded for her skill and empathy as a physician, she served as Associate Chief Medical Officer and Chair of Medicine at Rancho Los Amigos National Rehabilitation Center. She has spent most of her medical career working with individuals with disabilities and has witnessed the impact an injury has on quality of life and social isolation.

As a researcher at Rancho Research Institute (RRI), she spearheaded the awarding of grants from the Craig H. Neilsen Foundation and the Christopher & Dana Reeve Foundation to conduct RRI’s photography programs. She is also proud to have developed and led a federal grant-awarded project that studied cardiovascular risk factors in women with spinal cord injury.

At the University of Southern California’s Keck School of Medicine, Dr. Szlachcic holds an academic appointment in the division of Cardiology. Her research interests include women’s health, spinal cord injury, cardiovascular risk factors and secondary conditions, and quality of life improvement for individuals with physical disabilities.

She has a firm belief that music and art, particularly the visual arts, provide opportunities for rising above difficult circumstances and creating new narratives and experiences to share with others. Her vision and perseverance have led to heartwarming success stories and will continue to do so as the photography program is refined and expanded to deal with ever-changing conditions.

Nicole Bayus, MA

Nicole Bayus, MA is the director of Rancho Research Institute’s Clinical Trials Division. Under her oversight, RRI has consistently been a national leader in subject enrollment and retention, and her leadership of multidisciplinary research teams has earned the institute a reputation as a standard-bearer for research administration of the highest quality. The Photography as Therapy program was of the first projects she helped design and implement at RRI. She is delighted to have been a part of shaping this research and is honored to have worked with the talented and deserving students who gifted the program with their stories and their photographs.

Michael A. Ziegler, BA

Michael Ziegler, BA has been photographing people, places, and things for over half a lifetime. He loves the connection the camera affords when people see his enthusiasm and sense that he respects them and wants to share their images with the world. In the past several years he’s come to recognize how important teaching photography is, and how impactful it can be to reach out and share one’s passion and commitment with students who often need new goals and new directions after surviving traumatic injuries. It delights him to see many students blossom into dedicated photographers who can share their vision of the world, their world, with others.

![]()

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.