Reviving and Reflecting on "Portrait of Spirit: One Story at a Time"

By Melissa McCune

The groundbreaking book Portrait of Spirit: One Story at a Time1 was envisioned and created by award-winning photographer Billy Howard and nationally-renowned folklorist Maggie Holtzberg. It features photographs of 25 individuals alongside their personal and compelling stories that dance around a single shared characteristic: disability.

In the shadow of the 1996 Paralympic Games in Atlanta, GA, Howard and Holtzberg expertly wove their unique talents together to highlight individual stories of people living with disabilities. Published only six years after the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) was passed into law, Portrait of Spirit redefined what it meant to be living with a disability, and exposed the many hidden challenges that must be overcome each day to function within society. At such a pivotal time in history, Howard and Holtzberg opened the door to more meaningful dialogue on disability while providing new perspectives on the disability experience. By focusing on all aspects of each person’s unique story, they emphasized how disability represents only a piece of that individual. Featured in the Portrait of Spirit are artists, mothers, fathers, athletes, educators, advocates, and more, whose voices have been shaped from experiences that transcend their physical limitations.

Almost 24 years since being published, in an act of revitalization, the Journal of Humanities in Rehabilitation partnered with Emory University’s School of Medicine to host an exhibit of the images and stories told in Portrait of Spirit: One Story at a Time. The exhibit ran from October 7, 2019 through November 7, 2019 and served as a mechanism for people to pause, engage with, and contemplate stories that were different from their own. On the opening night of the exhibit, Billy Howard and Maggie Holtzberg, along with some of the individuals featured in Portrait of Spirit, reunited and joined the community in a panel discussion.This discussion revealed how these stories have evolved and provided insight into the continued societal challenges of living with a disability.

Maggie Holtzberg with Catherine Howett Smith at Portrait of Spirit panel discussion. Image used with permission by John Stephen Richard Hyjek.

Mark Johnson with Billy Howard at Portrait of Spirit panel discussion. Image used with permission by John Stephen Richard Hyjek.

Kate Gainer with Maggie Holtzberg at Portrait of Spirit panel discussion. Image used with permission by John Stephen Richard Hyjek

Tommy Futch with Al Mead at Portrait of Spirit panel discussion. Image used with permission by John Stephen Richard Hyjek

This article includes excerpts from Portrait of Spirit: One Story at a Time and offers reflections from photographer Billy Howard on the history that informed the development of this project, and on his personal motivation and experience working with people living with disabilities.

“Probably the thing that is most frustrating is that not everybody around me perceives me the same way I perceive me. …I have to recognize that when I meet people and when I’m trying to establish relationships or friendships, the disability is always in the forefront of their mind.”

Ann Cody, Paralympic athlete (Portrait of Spirit, p. iv)

A New Eye on Disability: Atlanta, 1996

In 1996, the people of Atlanta experienced disability from a new vantage point, as Paralympic athletes from around the world navigated the city to participate in the 1996 Paralympic Games. Billy Howard and Maggie Holtzberg describe this event as being a catalyst in the creation of the Portrait of Spirit project, as the following excerpt from the introduction to their book explains:

“This book came about, in part, because 1996 was the year Atlanta hosted the Centennial Olympic Games. Two weeks after the Olympics ended, the city welcomed the Paralympic Games, the ultimate competition for world-class, elite athletes with physical disabilities. Many of us were searching for ways in which to heighten the awareness of the Paralympic Games and seize the opportunity they offered to change able-bodied people’s perceptions of disability. A Cultural Paralympiad was envisioned, the first of its kind. …Paralympic athletes are not people who do well despite their physical limitations; they are people who do well, period. …It was with David Sampson that we began our work. As photographer and folklorist, we set out to gain an insider’s perspective. The hope was that nondisabled people would come to know people with disabilities, one story at a time.” (Portrait of Spirit, p. iv-v)

“Paralympic athletes are not people who do well despite their physical limitations; they are people who do well, period.”

25 Individual Stories, 1 Collective Voice

Howard and Holtzberg have an undeniable talent for capturing a person’s true essence. When collecting stories, they work to create a space where trust and self-expression run free; Portrait of Spirit is a testament to that talent. The 25 narratives offer moments of joy, sadness, resilience, and strength that can only be described as purely human. What follows is a glimpse at a few of these stories and the collective voice that rings out when stigma, biases, and preconceptions about people living with disabilities begin to fade.

“These individuals have fought long and hard about how they want to represent themselves to the nondisabled community. If there is a pattern to be discerned in their collective story, it is that they have succinctly reduced their lives to a personal story out of the necessity of defining themselves in a way that most of us do not have to.” (p. v)

Kate’s Story

“Cerebral palsy is a very different disability…it’s not socially acceptable yet. People don’t understand the movements…I say, ‘accept me.’ I’ve accepted myself.” (p. 87)

Image used with permission by Billy Howard.

“Kate Gainer was one of 18 students to attend Atlanta’s first special education class for black children. It was an empowering experience for a black child growing up in a Southern segregated city. She says the most frustrating thing she went through as a teenager with cerebral palsy was that she couldn’t “strut” like the other girls could. Gainer’s intelligence, spunk and warmth have made her an invaluable advocate for people with a disability.”(p. 85)

Lauren’s Story

“I run into people who stop me on the street and speak very slowly or very loudly because they think because I am in a wheelchair that I have a mental disability. They do not expect that I can do the things I do…It’s a surprise to a lot of people.” (p. 66)

“Lauren McDevitt was ten when she experienced a muscle cramp in her thigh. She went to the school nurse to lie down. Within an hour, she lost all feeling and movement from her waist down. She captured a bronze medal at the 1996 Paralympic Games in dressage, a test of ability of rider and horse to communicate and work together through a series of complex moves.” (p. 65) Today, Lauren has earned her Master in Rehabilitation Psychology and Counseling degree, is married with two teenage boys, and is the Director of the North Carolina Office on Disability and Health.

Image used with permission by Billy Howard.

Al’s Story

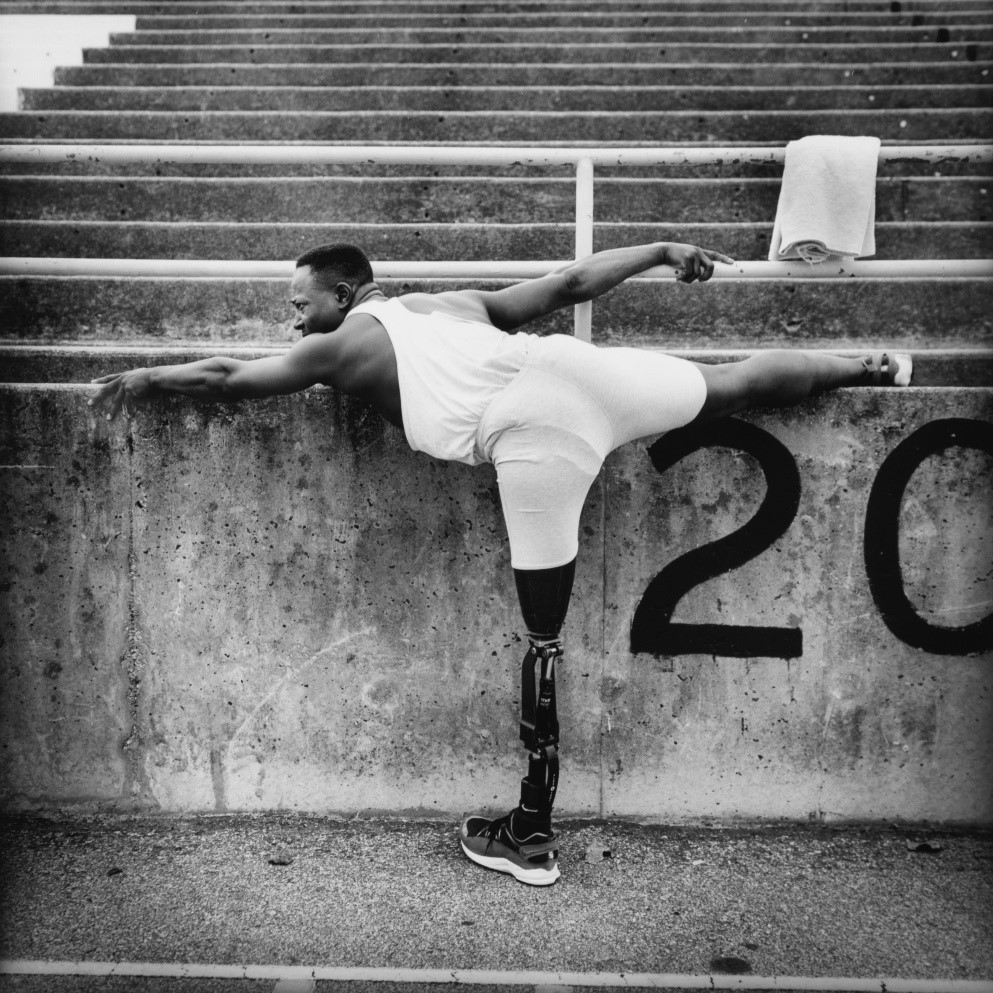

“I think everything finally came together when I started competing against other disabled people who were as competitive as I was. All of a sudden I had a group of people I could lean on and be a part of because they were athletes as well.” (p. 14)

Image used with permission by Billy Howard.

“As a youngster, Al Mead lost his left leg above the knee due to circulatory problems. Mead has grown into the quintessential Paralympic athlete, whose excellence in competitive sport is equaled only by his commitment to increased awareness of the abilities of persons with a disability. He holds a U.S. high jump record at 1.73 meters. He set the world record for the long jump with a gold medal performance in the 1988 Paralympic Games in Seoul, Korea. Four years later in Barcelona, Mead won a silver medal in the long jump and sang at the closing ceremony.” (p. 12)

Catherine’s Story

“I would not attempt to do anything unless it was perfect. I believed I had used up my quota of failure. I had always thought this handicap was some colossal failure and I had used up my allotment of being imperfect.” (p. 36)

“Catherine Howett Smith is Associate Director of the Michael C. Carlos Museum at Emory University. A progressive neuromuscular disease began weakening her legs as a child. Reflecting on her journey coming to terms with her identity as disabled, she describes the importance of her role as a mother: ‘Throughout my life I had a lot of self-confidence because of intellectual gifts, but not physically because of my disability. Having my daughter was so profound, because it was the first time I did something physical—the ultimate physical experience. My self-identity is complicated—but with my daughter it is so simple—I am just Mommy.’ ” (p. 36)

Image used with permission by Billy Howard.

Disability and Society: Looking Forward

When looking back over the past two decades, the progress our society has made since the 1996 Paralympic Games regarding disability seems obvious. The challenges faced by persons with disability may have become a bit less burdensome; a flicker of hope arises in the realization that society may finally be catching up with the extraordinary talents of this population. For many, however, there are new challenges and opportunities constantly arising as they continue to push forward. This perception of progress and its challenges looks different for each individual, as our stories and reasons for moving forward are unique and personal.

Encouraging members from both the disabled and nondisabled communities to come together to address issues of access, discrimination, and stigma that impact people living with disabilities is a critical step to jumpstarting change.

“This book is not so much about the subject of ‘the disabled’ as it is about the cultural context in which disability occurs. That culture is shaped by the fact that we live in a society which is largely uninvested in the experience of being disabled. Despite the enactment of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), physical and communicative barriers abound. Prejudicial attitudes towards people with disabilities are daunting.”(p. v-vi)

“…it is about the cultural context in which disability occurs.” “…we live in a society which is largely uninvested in the experience of being disabled.” (p. v-vi)

Interview with Billy Howard

In this interview, Howard describes his experience creating Portrait of Spirit: One Story at a Time, and reflects on the aspects of society that continue to present obstacles for people living with disabilities. He also weighs in on how he hopes Portrait of Spirit continues to serve as a resource for those in the rehabilitation community.

What was it like for you to create and be involved in this project?

Although I had been around people with disabilities since college, the experience of finding, meeting, listening to, and documenting the lives of the 25 people in this project inspired me, with their indominable spirit; shocked me, with the extraordinary efforts they were required to make in some cases just to get through their day in a world set up with obstacles the rest of us cannot fathom; angered me, with the loopholes that allow companies to discriminate against those with different abilities; and filled me with hope, through the stories of grace and pure will these individuals shared with us.

Did this project touch on any personal experiences for you?

This project was deeply personal to me. I attended St. Andrews College (now University) in North Carolina, which was one of, if not the first, barrier-free campus in the country, allowing people with physical disabilities to attend college with full access to classes and social activities. As a result, the campus was diverse not only along racial, ethnic, and religious factors, but also diverse in physical abilities. What I discovered at a time when I was coming of age, was that we all had different abilities and disabilities. I left St. Andrews with friends that informed my life as an adult.

What most surprised you about the experience?

Every documentary project is filled with the same surprise, and it is the thing that continues to motivate me to continue through a project’s obstacles and setbacks. That is the wonder and joy in having people share their most personal stories and reveal to us their challenges, pains, loves, and fears. Surprise may not be the right word in this case; it is more like awe.

Describe how you and Maggie worked together and influence each other.

I think what Maggie [Holtzberg] and I share in our work is an innate curiosity about humanity and a desire to discover and learn from people who have different experiences than us. Maggie shares that with others through her exceptional skills as an interviewer. When I was with her on interviews, I would sometimes leave forgetting that she had interviewed the subject; it had been more like witnessing an intimate conversation between very close friends. The revelations came from a trust she was able to build in a short amount of time. Some people were speaking of things that were deeply painful to them; Maggie gave them the confidence that their words would be honored and respected. I have tried to work the same way with the people who I photographed, making us a natural fit. I tried to take portraits that would honor the spirit of life they were revealing to us.

You have created many other projects that dive into this exploration of the human experience. How did this deep and genuine desire to know “the other” develop?

My alma mater, St. Andrews, was an introduction to people who I would have thought were very different from me and the beginning of a life-long discovery process that revealed the beauty in how we can learn, connect, and grow best by being around people that can bring us different perspectives. I have always sought out people, especially in my work, that bring me a broader understanding of the world through their different experiences.

What artist has most influenced your own work?

When I was in high school, I discovered the photography of Dennis Darling and saw how he used the camera as a ticket to explore the lives of people he never would have had access to without photography. Some of these were people with moral flaws, some were people in exotic locales, and some were heroes. The common denominators were a camera and curiosity. In a great act of serendipity, I was able to meet him and we became lifelong friends. He is still a mentor to me and my work.

How did this project impact how you view your own life?

It makes me profoundly thankful. I have had my own struggles with pain and illness (haven’t we all) including a form of arthritis that at times challenges the work I do. I have, quite literally, called on the strength of the people I met through this work, humbling myself with my own minor issues, and, as the Brits would say, carrying on.

In the 24 years since the birth of this project, how do you feel society has evolved (or not), and what needs to change?

While there have been many technological changes that have allowed people—through the use of computers and enhanced prosthetics, among others—to live life without as many obstacles, the loopholes within the Americans with Disabilities Act have also kept society from moving as fast as it should in breaking down the physical barriers to access for people with disabilities. We learned that firsthand recently as we went to a restaurant to celebrate the revival of our exhibit only to find multiple obstacles to those among us in wheelchairs that blocked access to the building.

How did you navigate that fine line between celebrating the “human spirit” and falling into the “super-crips” trap?

Our subjects made it very clear to us from the beginning that they didn’t see themselves as heroes, but merely people who lived life like the rest of us, but with more visually apparent hurdles. One of the people we included was former U.S. Senator Max Cleland, who lost one arm and both legs in a grenade mishap in Vietnam. He wrote a book, Strong at the Broken Places, which said that we all have injuries we need to heal, it’s just that with him and others with disabilities, those injuries are more visible. That philosophy is so powerful to me, basically saying we are all in this together, we must all have empathy with each other.

How do you think this exhibit impacts clinical care and rehabilitation science education?

I cannot imagine wanting a career in healthcare in any field without first having a deep sense of empathy for people, and particularly people whose lives can be improved through understanding, science, and medicine. My hope is to, through the interactions this project allows between the viewer and the people we photographed, create an enhanced understanding of how people in the medical/rehab fields process what they have learned and how they use their skills. Through Maggie’s interviews I hope it opens them to new ways to connect to their patients, and, hopefully, through my photography, they can look into the eyes of those they serve with a deeper desire to understand who they are as people. My desire would be for them to see the person first, not the disability. That makes all the difference.

How do you envision this book and exhibit moving forward through the rehabilitation community?

My deepest hope is that those on the service side are inspired by the voices of those in this work and gain a more profound sense of the beauty and nobility in the work they do and that those who are dealing with their own physical disabilities, especially those who are entering into this world for the first time, can see that they can live a full and wonderous life and that their disability will always be a lens through which they see it, but not the only one. They should never feel reduced by their disability, but lifted by their own humanity.

About the Authors of Portrait of Spirit: One Story at a Time

Billy Howard is a 2011-2012 Rosalynn Carter Fellow in Mental Health Journalism. He is the author of Epitaphs for the Living: Words and Images in the Time of AIDS; Portrait of Spirit: One Story at a Time, images and interviews of people with disabilities with an introduction by Christopher Reeve; and Angels and Monsters: A Child’s Eye View of Cancer with an introduction by Jeff Foxworthy. His photographs are in the permanent collections of The Library of Congress, the High Museum of Art, The Carter Presidential Center, and The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. In a tribute to Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Howard’s photographs were projected on the stadium screen during the opening ceremonies of the 1996 Olympic Games in Atlanta, GA. His photographs are featured in the book Pandemic: Facing AIDS with an introduction by Kofi Anan, edited by Rory Kennedy. He received an Honorary Doctor of Literature Degree from St. Andrews University in North Carolina in 1996. Readers can learn more about Howard’s distinguished career here.

Maggie Holtzberg was the 2018 recipient of the American Folklore Society’s Benjamin A. Botkin Prize, recognizing her lifetime achievement in public folklore. She is currently the Manager of the Folk Arts & Heritage Program at the Massachusetts Cultural Council. As a folklorist, she works closely with traditional artists and communities through documentary fieldwork, grant programs and technical assistance. She has conducted field research throughout the state of Massachusetts documenting traditional arts, and established a traditional arts archive. She is the author of The Lost World of the Craft Printer (1992); Portrait of Spirit: One Story at a Time (1996); producer of the sound recording Georgia Folk: A Sampler of Traditional Sound (1990); and co-director/producer of the documentary film Gandy Dancers (1994). Holtzberg holds a PhD in Folklore and Folklife from the University of Pennsylvania and served as Folklife Program Director of the Georgia Council for the Arts prior to moving to Massachusetts.

References

- Holtzberg M, Howard B. Portrait of Spirit: One Story at a Time. Oakvillve, Ontario, Canada: Disability Today Publishing Group, Inc., 1996.

Member since 2019 | JM14274

Member since 2019 | JM14274

NO COMMENT