Finding Help: Exploring the Accounts of Persons With Disabilities in Western Zambia to Improve Their Situations

By Shaun R. Cleaver, PT, PhD; Stephanie Nixon, PT, PhD; Virginia Bond, PhD; Lilian Magalhães, OT, PhD; Helene J. Polatajko, OT, PhD

Abstract

Background: Strategies proposed to improve the situation of persons with disabilities in the global South are not always developed in consideration of local contexts.

Purpose: To explore and develop strategies to improve the situation of persons with disabilities in one context in the global South.

Method: We recruited two groups of persons with disabilities in Western Zambia. Eighty-one disability-group members participated in focus-group discussions and individual interviews, with a North American rehabilitation professional, in which they discussed life with a disability and what should be done to improve their situation. The transcribed audio-recordings of the focus-group discussions and interviews were analyzed thematically.

Results: The accounts of ways to improve the situation of persons with disabilities in this context were framed around a single theme: help (“kutusa” in Silozi). When expressed by participants in this research, help refers to gifts or grants of material resources from those with the means to share but influenced by the presentation of need by potential recipients. Help occurs in a relationship of expected compassion.

Conclusion: Help is very different from formal strategies that are currently being promoted to improve the situation of persons with disabilities in the global South.

Keywords: global South, postcolonial perspective, poverty, qualitative research, rehabilitation

Introduction

Disability: a global issue best addressed together with those who experience it.

According to the World Health Organization,1 there are more than one billion individuals worldwide who can be considered disabled. The majority of these individuals are in the global South—countries seen by the World Bank as low- and middle-income in Asia, Africa, Latin America, and the Caribbean. The global South, with more persons with disabilities (PWDs) than the global North (a collective term for the richer, more industrialized countries of the world), has fewer formal structures (ie, programs, services, policies) to support PWDs.1 Accordingly, studies of the living conditions in the global South have identified substantial unmet needs.2-5 This problem has led to calls for action to improve the situation of persons with disabilities (PWDs) in the global South through formally-supported strategies (ie, those for which external actors such as governments or non-governmental organizations provide support).1

Critics informed by a postcolonial disability studies perspective6,7 have observed that formally-encouraged strategies are often supported by a knowledge base that is exported uncritically from the global North and applied to the global South without consideration of its (in)appropriateness.8-10 Dominant worldviews in the global North, such as the moral, medical, and social models of disability,11 therefore have a direct bearing on the formally-supported strategies aimed at improving the situation of PWDs in the global South. A key point of this critique is that de-contextualized trends and orthodoxies dominate what is considered to be possible—overshadowing or disregarding the voices of the actual people who live with disabilities in the global South.12,13

Listening to the voices of PWDs in a particular context is consistent with the General Principles of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD)14 and likely would be more effective at meeting people’s actual needs.15 Given that the global South is not a singular and homogenous entity,16 it is reasonable to expect that dialogue and allyship17 with PWDs ought to be contextually-grounded. Nonetheless, it is possible that lessons learned in one context can be transferred to another context, provided these unique lessons are considered carefully and critically. One proposition regarding the conditions for transferring lessons between contexts is offered through Indigenous Project #24, “Discovering the beauty of our knowledge,” as presented by Linda Tuhiwai Smith.18 According to Smith, it is necessary to centralize the local and the traditional aspects of a given culture, before considering the potential of imports to offer new insights into it.

Purpose

The purpose of this study was to explore and develop alternative strategies to improve the situation of PWDs, as informed by dialogue that is grounded to a specific social and geographic context in the global South. The social context was that of a North American rehabilitation professional interacting with two disability groupsThe geographic context was two sites in Western Zambia—one urban, and one rural. The specific research question asked was:

How are strategies to improve the situation of PWDs framed within the accounts of two participating disability groups, one urban and one rural, in Western Zambia?

Methods

This study was part of a larger project, the methods of which have been described in detail elsewhere.19-21 The larger project was designed as qualitative constructionist research, with a “focus upon how phenomena come to be what they are through the close study of interaction in different contexts.”22 The project was also designed with attention to participatory research principles (participant involvement and an action orientation)23 and critical perspectives applied to the research process (consideration of ideology, power relations, contradiction, and the dialectic between structure and agency).24 The study was conducted in Zambia’s Western Province, an area with 900,000 residents, the majority of whom live in rural areas.25 Western Province is relatively undeveloped and has high levels of poverty and the highest disability prevalence among Zambian provinces.25 Although the population now includes people from a variety of tribal backgrounds, the Lozi language (Silozi) and culture still predominate in Western Province.

Study Team and Positionality

The principal investigator (PI) for this study was a PhD student researcher from Canada, supported by a “supervision team” of experienced academics from Canada and Zambia. The PI is a rehabilitation professional (a physical therapist) by background; he had worked to develop disability and rehabilitation programming in other countries of the global South. Through the experience of doing this work, he began to question that logic by which rehabilitation providers—including himself—traveled from the global North to the global South, carrying rehabilitation services with them into new contexts without questioning their appropriateness. The idea to explore and develop strategies to improve the situation of PWDs in a specific context emerged from the PI’s previous professional experience. In the initial conceptualization of the study, the PI conceived of “strategies” loosely, with the intention of allowing possibilities to emerge through the study. It was envisioned that strategies might be programs, activities, services, policies, or initiatives that were operated by the government or civil society actors (especially PWDs themselves). Nonetheless, the study team approached the project with an interest in strategies that could be very different from what was envisioned.

The PI lived in Zambia for just over one year to conduct this research. He initially spent six months in the capital of Lusaka to prepare the project with national-level Zambian partners, in particular the Zambia Federation of Disability Organisations (ZAFOD). Upon the suggestion of the leaders in ZAFOD, the PI relocated to Western Province to conduct the research. The PI self-identified as a White non-disabled male in his 30s who grew up in Canada with English as his first language. He was learning local languages over the course of the study and attained basic functional capacity in Silozi. Study activities, including recruitment, data generation, logistical planning, and transcription were supported through the work of five paid research assistants from Western Province. All grew up in Western Zambia speaking local languages as their mother tongues. All considered themselves non-disabled, were in their 20s, and were either post-secondary students or recent graduates. Three of the research assistants were women and two were men.

Study Participants

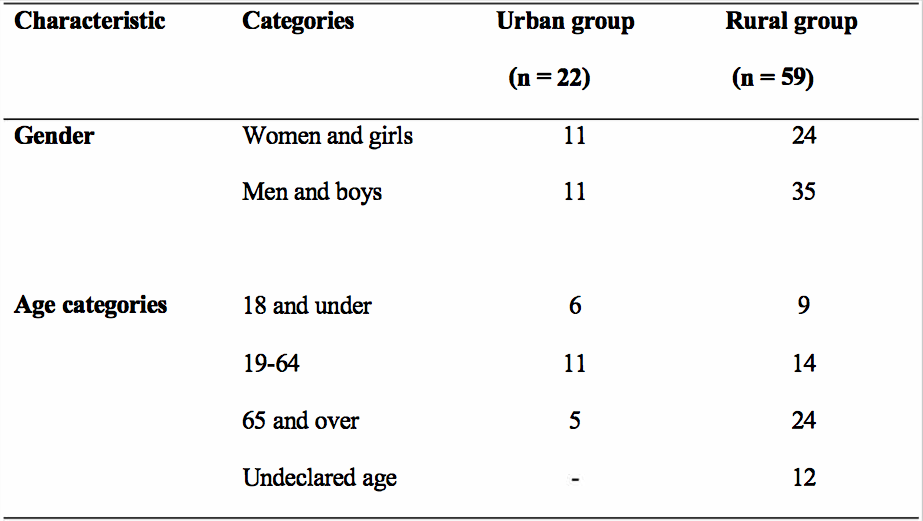

A two-stage recruitment process was used for this study. The first stage of recruitment was for disability groups—one in the provincial capital of Mongu, the other in a remote area of a rural district.20 ZAFOD leaders suggested that the PI engage with specific Government of Zambia offices, which in turn identified disability groups. The two groups that were identified could be considered to be self-help groups for persons with disabilities.26 Each group was approached through its leadership. After the groups’ leaders agreed to participate, the individual members of the groups were approached for their consent. In the case of members who were children with disabilities, the consent process and data-generation activities were conducted with the parents, involving the children according to their interest and capacity. Twenty-two (22) members of the urban group participated in the data-generation activities, while 59 members of the rural group participated.21 An overview of the demographic characteristics of the participants is presented in Table 1. No participants withdrew from the study.

Table 1: Participant Demographics

Data Generation

Data were generated through focus-group discussions followed by semi-structured interviews, followed by a second set of focus-group discussions. The PI led all data-generation activities. To allow participants to speak in the language of their choice, a research assistant fluent in multiple local Zambian languages performed real-time translation.

The first round of focus-group discussions and the interviews were based upon a similar premise: open-ended questions about life with a disability and how it could be improved. Through these questions the participants were asked to describe their disabilities and their lives from their own perspectives. They were also asked about the strategies that did or could improve their situation. By the second round of focus-group discussions, the PI had come to know the participants and the area far better.

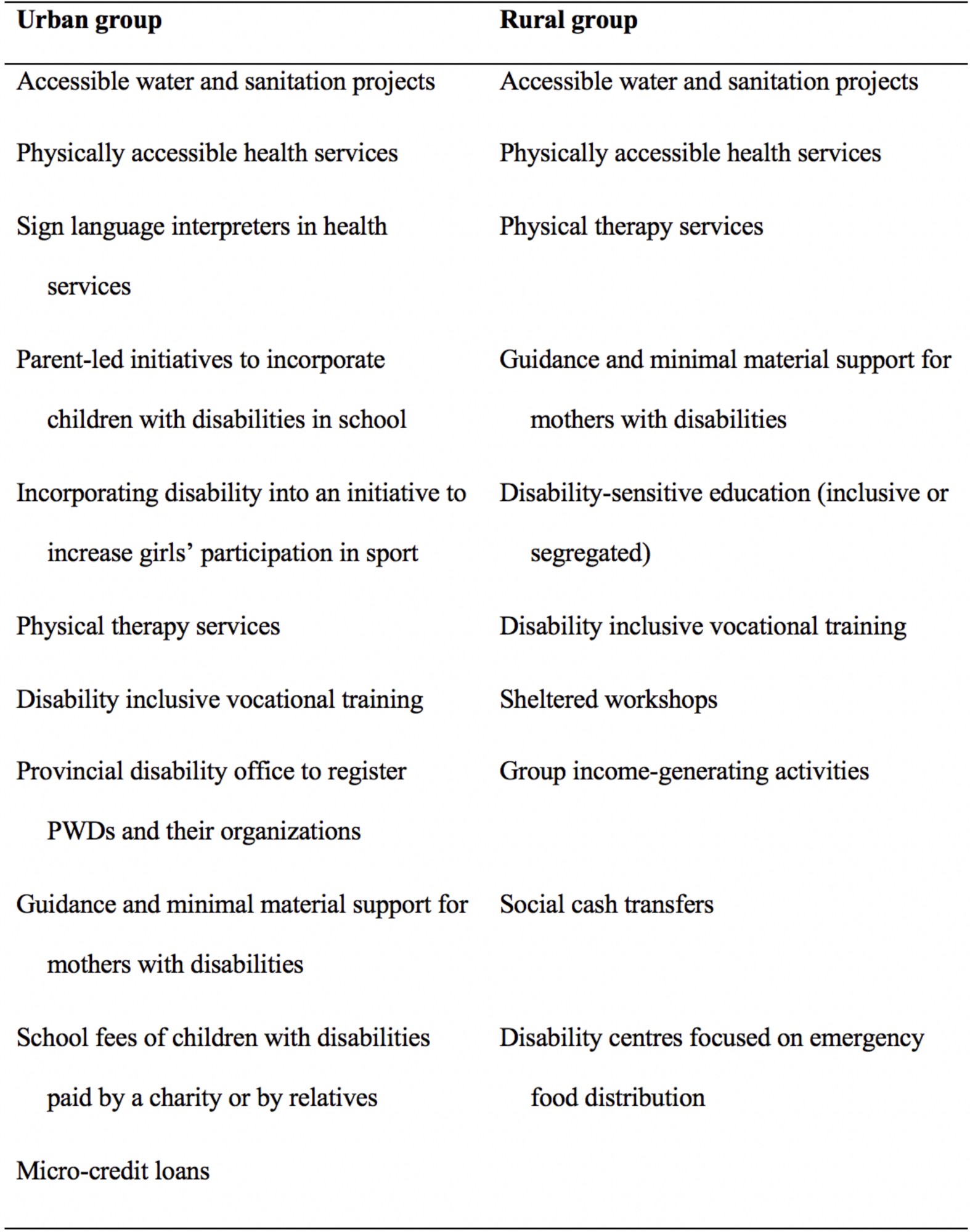

For the second round of discussions, the PI created a list of specific strategies that he had learned through the data-generation activities and interaction with local service providers, presenting each strategy during the focus-group discussion and allowing participants to share their understanding and opinions of these strategies. The strategies presented to the two groups are shown in Table 2.

All data-generation activities were audio-recorded and all speech was transcribed by the research assistants. Transcription was performed according to procedures described in a transcription guide drafted by the research team.

Table 2: Strategies Presented to Participants in the Second Round of Focus-Group Discussions

Data Analysis

The analysis of these qualitative data was conducted by the PI with the guidance of the supervision team. Data analysis was guided by the principles of thematic analysis described by Braun and Clarke.27,28 Specifically, the process began with a detailed reading of all transcripts. This reading helped to inductively develop an initial code book. The PI used the initial book to code all of the transcripts using NVivo10, over the course of six months. The content of the initial codes was used as the foundation of an iterative analytic and writing process that lasted an additional 16 months. As part of this process, the PI created schematic diagrams to visually relate ideas that had been developed through the initial coding. In creating the diagrams, the PI was able to see the data differently and develop new and different codes. The diagrams and codes were used to inform initial write-ups of the analysis that in turn influenced the codes and the diagrams. Although the PI conducted the analysis, the supervision team provided frequent feedback and advice about the analytic products.

Parallel to the analysis of empirical data, the PI also engaged in reflexive analysis. The reflexive analysis yielded insights that were published separately while simultaneously influencing the empirical analysis. Insights from the reflexive analysis included an assessment of the ways that the research context undermined the global health research principles29 of authentic partnerships and shared benefits30 and an exploration of the ways that the research project was unknowingly oriented toward productivity.31

Ethical Considerations

Research ethics approval was granted by the University of Toronto Health Sciences Research Ethics Board (Protocol reference #29653), the University of Zambia Humanities and Social Sciences Research Ethics Committee, and the Zambian Ministry of Health. Practical ethical considerations included supporting travel costs when paid motorized transportation was available and providing a meal for focus-group discussions or snacks for meetings. The identities of participating individuals and groups are described in general terms to allow readers to comprehend their situation while maintaining anonymity.

Results

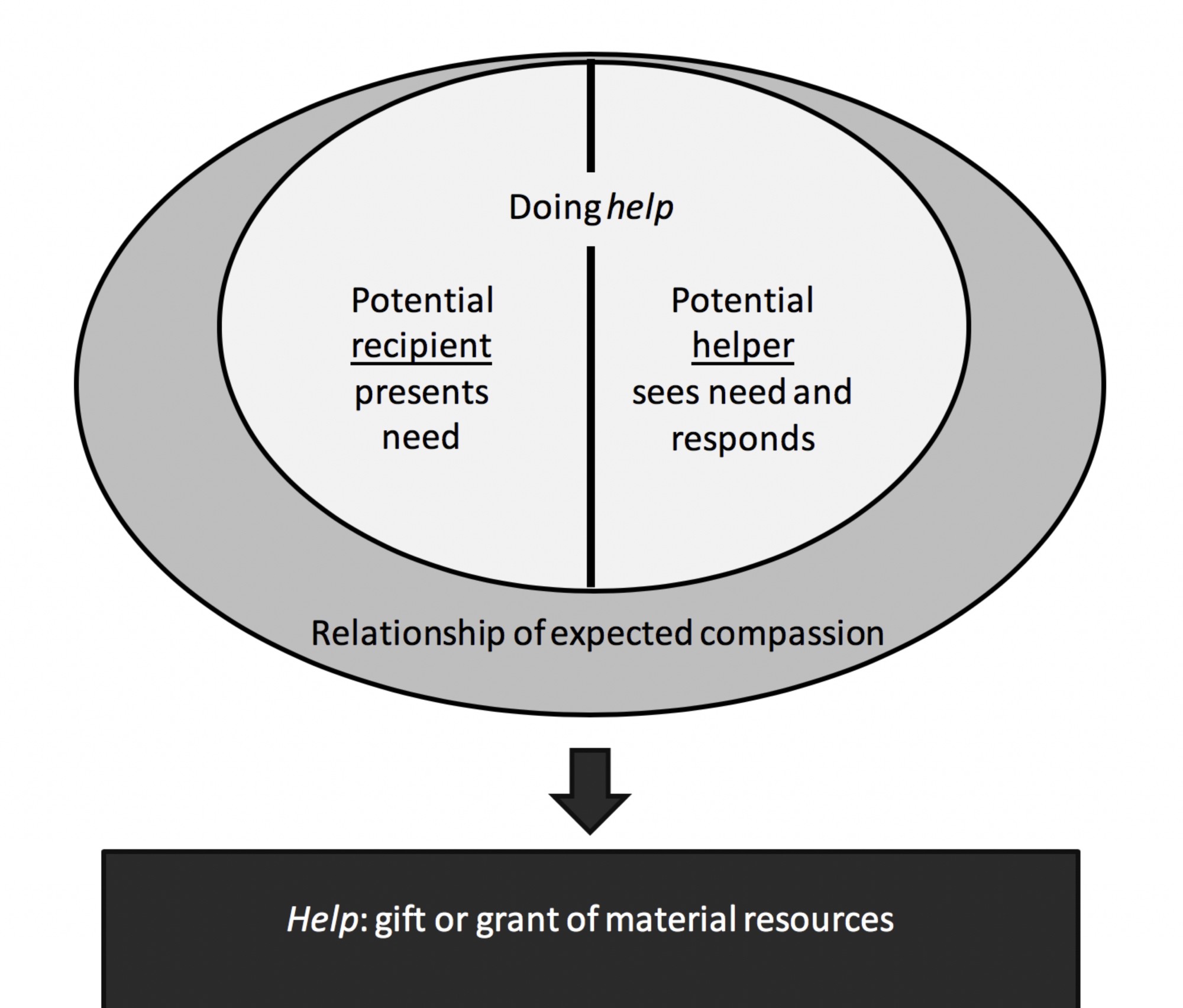

The purpose of this study was to explore and develop alternative strategies to improve the situation of PWDs, as informed by dialogue that is grounded to a specific social and geographic context in the global South. During data-generation activities, when asked about things that improved their situation, the participants of this study tended to not mention the types of formal strategies envisioned by the PI. When participants were presented with the list of strategies identified by the PI (primarily through his interactions with service providers), the participants responded with general disinterest. Instead, they framed strategies to improve their situation through a single theme: kutusa (Silozi for help). When speaking of help, the participants described the phenomenon according to a particular meaning, with specified ways of “doing help,” and according to a given rationale. The facets of help are represented visually in the Figure; each facet is described individually below.

Figure: Visual Representation of the Characteristics of Help as the Way Forward by Groups United by the Issue of Disability in Western Zambia

The Meaning of Help

When referencing help, participants were generally speaking of gifts or grants of material resources (ie, money and things that can be purchased with money), as captured by the following interaction:

Interviewer: When you say “to help those people who are suffering,” what do you mean?

Participant: I mean that if you can help us so that we can also help ourselves.

I: So when you say “so that you can help yourselves,” what do you mean by that?

P: Helping us really.

I: I still don’t understand.

P: Helping us, that if you find a little something, then you give us.

—Woman with a physical impairment due to leprosy, rural group

During the data-generation activities, the participants spoke repeatedly about the lack of material resources as a fundamental problem of living with a disability. Accordingly, it follows that the speaker is suggesting that the “little something” that could be given is money or things that can be purchased with money.

In other cases, participants were less specific about the gift element of help, but were more explicit that help was money:

Interviewer: But I wonder what type of support would actually be helpful to make more people succeed. What do you think?

Participant: This time around, help is centered on money. There are some people who would want to buy some oxen, plows, and other implements but they cannot because of lack of funds.

I: Certainly, yeah.

P: So our money, our livelihood, is centered on money, everything depends on money.

—Man with physical impairments, rural group

In the quote directly above, the participant included a time marker in his account (“this time around”), possibly in referential comparison to another period when help might have been equally necessary but different in nature. In this case, money was mentioned as being necessary, even if the utility of this money was for conversion into other resources.

In some instances, participants spoke of help in terms of material items. One participant from the urban group referenced a supply of food, including beans and maize meal, as examples of “things which have come to help people.” Another participant from the urban group spoke about how he needed oxen to farm and that these could be provided through help. According to this participant, “there is a lot of help we need for us to survive.”

Although the descriptions of help may have seemed varied in the sense that they included money, money to buy resources, and the direct provision of the resources, these possibilities were presented in a fluid, practically interchangeable fashion. Due to this fluidity, the substance of help is best identified as material resources—an umbrella term to encapsulate money and things that can be purchased with that money.

Regarding the method in which material resources are transferred with help, participants spoke of help in ways that are similar to gifts or grants. Although this description involved the PWDs acquiring material resources without payment, there was more nuance and detail with respect to the practice and expectations of help than it merely being a selfless and voluntary act on the part of the donor. These details are presented in terms of the practice of help and the rationale behind it.

Doing Help: the Who and the How

Participants spoke of patterned roles that helpers and recipients play in a process that could be referred to as doing help. A participant from the rural group, an older man with a physical disability, described the important role of the helper in initiating help: “It’s that [helper] who should choose that ‘I can help this one but I will not help this one; I am helping maybe this one because of maybe the way he is and I will not help this one.’ But it is chosen by the one who is supposed to give, not the person who is supposed to receive.”

With the prominence of help as an intervention strategy to improve the situation of PWDs, the identification of helpers and recipients was crucial to understanding disability. According to that participant, persons with disabilities were those “who need to be helped,” although he mentioned that the elderly also shared this characteristic. Connecting these considerations, it seemed as if disability status could only be validated by helpers. This possibility was reviewed with the participant:

Interviewer: So that means that it is only people who have things to give that can decide “this one is disabled and this one is elderly.”

Participant: The one who gives is the one who sees.

Participants repeatedly emphasized the importance of “those who have things to give.” In some instances, these people would be “well-wishers”: individual neighbors and friends who would help with gifts of food and supplies. In other instances, helpers were institutions, such as religious, civil-society, or governmental entities. Within these interactions, participants spoke of the power of the helpers to specify the recipients, nature, and quantity of help to be provided. Nonetheless, the potential recipients had a role to play in facilitating the provision of help. When speaking of the process that the rural group could follow to improve their situation, the commonly-identified informal group leader cited the key role of institutional helpers: “We ask the money from the government…we tell them that ‘we want to do this, we want to do this’ and then when they feel mercy [makeke] for us, they can give us, then from there, we can change other things.”

Beyond discussing help, the participants engaged in the process of doing help, as potential recipients, within the interactional context in which the data for this study were generated. The PI was a person of privilege relative to the participants; he was approached by participants with numerous requests for help. One direct request came from a participant from the urban group who matter-of-factly stated during an individual interview that he joined the study so that the PI would build him a house. Another direct request was from an elderly participant in the rural group who declared to the PI during a focus-group discussion that, “You will help us!”

Although a few requests for help were direct, many other potential requests were ambiguous, couched in humor or subtlety. Among the likely requests was a proposal from a participant in the urban group during a focus-group discussion that the PI “can be my pen-pal (laughs) and help me.” During an individual interview, another participant from the urban group outlined a series of expenses that he was facing before stating to the PI, “If I was to find a donor who can help me with those things I can feel very happy.”

In discussing and doing help during this study, participants emphasized their roles as recipients. Often, this role was reinforced through its connection with impairment or disability status. Nonetheless, there were exceptions to this pattern—situations where a person with a disability could be a helper instead of a recipient. One was a reference from a parent with a disability in the urban group about helping his children. Other references were from the leaders of each of the groups. The urban group had a formally-recognized chair, whereas the rural group had one member who was informally considered to be the main leader. Both leaders appeared to be of a higher economic status than other members, with the larger and nicer houses of these leaders serving as meeting places for the groups. In both cases the leaders spoke about help that they offered to other members in the group, even though these contributions were small as compared to the help they hoped to secure for the group.

The Reason Behind Help: Expected Compassion

Participants rationalized the practice of help through a relationship of expected compassion between people of different economic and ability statuses. Specifically, participants spoke of help as being motivated by a feeling of makeke on the part of the helpers. The research assistants initially translated the Silozi makeke into the English words “pity” and “mercy,” but in the instances where participants spoke of makeke they implied more of a sense of warmth and caring than is meant by pity or mercy. A dictionary translation of makeke into the English word “compassion” seems a better fit to the participants’ descriptions.32

With compassion as a motivating sentiment and helpers able to choose whom to help and how, it might seem that help was directed solely by the internal compasses of those with adequate resources to be potential helpers. On the contrary, participants spoke of an expectation to receive help, and expressed disappointment when they felt that a potential helper had the capacity to help but did not do so in the face of legitimate need. According to a participant in the urban group, “I have relatives who are really working. But there is no help that I receive from them.” Another participant from the urban group spoke of the way in which acquaintances did not share with her family since they “do not like me because I have nothing to give them,” forcing her to beg for food from others.

The expectation of help was not limited to individuals; it also applied to institutions. A participant from the rural group focused his expectations on the government instead of neighbors: “Even when you would sit without food or you die without food you can’t go there because if you go there you know that they will not give you food. Or if you go there to say ‘I don’t have blankets to cover myself.’ We have maybe 10 years without finding blankets to use in [this community].”

Another participant, this one from the urban group, spoke of her expectations that a non-governmental organization would provide help, during a focus-group discussion: “One time I went there; I did not have maize flour. I went there to ask if they can help me, but they just gave me 2 lumps of nshima [the maize-based staple food] and some cooked beans.” The other participants broke into a disappointed laughter upon hearing of this insufficient form of help.

Since nearly all of the discussions about help were framed from the position of potential recipients, there are few explanations of the motivating factors from the perspective of a potential helper. One exception to this was the man considered to be the leader of the rural group. This participant with a physical disability owned a small shop and stated that “when I have something, then I give.” He spoke of his practice of helping others in compassionate terms, taking salt from his shop and giving it away. And yet in describing the way he selects the recipients, there was an element of strategic distribution: “Like this time you remember giving this one; this time you give someone else.”

Participants spoke of help as being motivated by compassion, yet it seems that compassion is not completely voluntary. Instead, compassion is expected, by the potential recipients at the very least. Taken together, potential helpers and potential recipients within a given community seem to be bound together through a relation of expected compassion that is manifested through the practice of help.

Summary of Results

Within the accounts of participants, help was framed as a predominant strategy to improve the situation of PWDs. Participants spoke about help as essentially a gift or grant of material resources. Help was enacted by potential helpers and recipients playing specific roles. Participants spoke of these roles in reference to relationships outside of the research, but also performed the role of potential recipient during the data-generation process. Participants spoke of a relationship of expected compassion as the motivating force behind help.

Discussion

The strategy co-constructed in this research, help, is fundamentally socio-economic. Help is economic in that it is a mechanism to distribute scarce resources. Help is social in that it is built upon human relations and expectations of compassion. To some, help might appear to be an unusual strategy to improve the situation of PWDs, especially for individuals enculturated in the knowledge systems of the global North. This was the case for the study team: it was not foreseen that participants would wish to discuss a strategy like help so frequently and emphatically.

To better understand how help can be conceptualized, the study team compared the strategy co-constructed in the research to three other ideas: (1) the conception of gifts as elaborated by Mauss;33 (2) the understanding of the social nature of “African economies” as described by Maranz;34 and (3) Zambian humanism as articulated by Kaunda35 and then reviewed by other Zambian scholars.

Similarities Between Help and Mauss’ Conception of Gifts

Marcel Mauss authored a seminal text on gift-giving that proposed that the practice can be simultaneously self-interested and disinterested.33 Mauss was a French sociologist active in the first half of the 20th century. His study of gift-giving was a review of ethnographic research from Indigenous tribes around the Pacific Ocean and ancient legal texts.33 The prime value of “Mauss’ system of The Gift”36 is that it stands in relief to the Eurocentric modernist conception that self-interested economic activities are distinct from disinterested (or selfless) charitable activities.

The argument proposed by Mauss is that the distinction between economy and charity is recent and self-imposed, to society’s collective detriment. To this effect, Mauss saw the modern conception of gifts as purely charitable acts as being flawed for its attempt to eliminate the possibility of reciprocity.37 Other authors have built upon Mauss’ foundation by discussing gifts in the contemporary global North, expanding the conception beyond material items to include abstract aspects such as advice and volunteer labor.38,39 Specific to international relations, authors have referred to Mauss in order to better understand development practices40 and development assistance.36

In discussing their situation and ways to improve it, participants in our study spoke frequently about help, but generally described it in terms of who should give what to whom. This conception, and the emphasis upon material resources, is similar to Mauss’ description of gifts,33 while being dissimilar to abstract aspects of gifts. Moreover, the participants’ accounts included references to people in particular roles relative to one another, and of relations that can grow and strengthen through the exchange, which is also similar to Mauss’ conception of gift-giving.

It is tempting to identify the consistency between the accounts of these participants and Mauss’ original descriptions as both emerging in traditional societies (if we consider contemporary Western Zambia to be culturally traditional), but this explanation ignores the extent to which participants spoke of money, the central medium of transaction in modern economies. An alternative to this explanation is more likely. The emphasis on material resources could be a direct result of the context of this research: the most prominent concern of participants was poverty,21 and the PI could be seen as a potential source of these resources. The combination of these two elements likely influenced the participants’ focus on material gifts as opposed to alternatives.

Similarities Between Help and Maranz’ Description of “African Economies”

Unlike the seminal academic contribution of Mauss, David Maranz has provided a practical guide to help Africans and Westerners navigate the day-to-day challenges of differing understandings of societies and economies.34 Maranz is an American anthropologist and Christian missionary who lived in various locations in West Africa. Maranz readily admitted that one should not homogenize either Africa nor The West (ie, the global North), yet sought to present characteristics that could be understood as generally accurate for both Africans and Westerners. Although not explicitly influenced by Mauss, Maranz’ presentation of the generalities of “African economies” is similar to Mauss’ conception of gifts in that each is designed to enhance collective solidarity. Maranz’ overt connection of “socio” to “economic” is also similar to help.

Since Maranz’ contribution was grounded in Africa, it is likely to be even more relevant to this study’s context in Western Zambia. Moreover, Maranz presented two ideas that are useful in thinking about help: (1) asymmetry, and (2) microsolutions.

Asymmetry. According to Maranz, many of the socio-economic practices common in Africa have developed in order to facilitate collective needs in situations of asymmetrical wealth. Through practices that are collectively understood in many African societies, “patrons” provide material support in exchange for respect, reverence, and the possibility of future reciprocity. Participants in this research clearly identified themselves as potential recipients in need of support from helpers. Participants spoke explicitly of the rationale motivating helpers as compassion, and indirectly about expectations, but is it possible that there is more nuance to this rationale than what can be derived from the data? Compassion is consistent with a sense of collective concern and solidarity, suggesting that Maranz’ explanations could inform the concept of help. Furthermore, some participants included their inability to reciprocate as part of the reason that they have not yet received help. Taken together, the co-construction of help seems consistent to the principle of asymmetrical exchange for communal well-being as described by Maranz.34

Microsolutions. In addition, Maranz proposed that many aspects of life in Africa are socio-economic microsolutions. In describing microsolutions, Maranz claimed that these are ways to immediately address problems on a small scale without challenging larger structures in an environment with significant uncertainty.34 The disadvantage that PWDs in Western Zambia face is likely longstanding and probably maintained through systematic society-level factors. Despite these characteristics, the participants in this study identified the microsolution of help as a preferred strategy to counter disadvantage and improve their situation. The consistency of help with Maranz’ descriptions of “African economies” allows for a more comprehensive understanding of socio-economic norms that could underpin participants’ suggestions of help as a strategy to improve the situation of PWDs.

Similarities Between Help and Zambian Humanism

Zambian humanism is a specific articulation of humanism, an ethical and philosophical approach that emphasizes the value and agency of humans.41 While Mauss and Maranz are anthropologists from the global North, Zambian humanism was developed by Zambians and is typically credited to Zambia’s first president, Kenneth Kaunda.35 According to Zambian humanism, it is incumbent upon all individuals to contribute to the well-being of the collective, according to their capacity to do so.

Some essential characteristics of a Zambian Humanist approach to community include sympathy, goodwill, and remembering the underprivileged.42 When compared with help, these characteristics are duties that would be assumed by helpers, such that those who have resources share these with PWDs who are in need of resources. Zambian humanism recognizes that although individuals have agency, there are also collective and societal forces that influence human well-being. The interplay of individual agency for collective benefit amid societal forces is apparent in the following statement from Kaunda: “A man [sic] is expected to share what he has with another man who has none, in order to ‘make it possible for him to enjoy the same privileges that society has bestowed on you.’”43

Zambian humanism presents an approach to life that reconciles traditional Zambian values and modern realities.43 In this respect, the project of Zambian humanism shares some commonalities with this study’s approach to strategies to improve the situation of PWDs through a contextually-grounded dialogue between insiders and an outsider. In contrast to this study’s North-South approach, Zambian humanism is Afrocentric, offering a perspective that could be even further detached from the trend of formally-supported strategies being influenced by perspectives from the global North.

The Relevance of Disability as a Problem to Be Addressed Through Help

Since the main finding of this research was help, a socio-economic solution, it is possible to think that disability was irrelevant or absent. This was not the case. First, for the participants, the primary concern in their lives was poverty, a concern that they saw as inherent to the experience of disability.21 According to this framework, disability and poverty were almost inseparable. Furthermore, the participants made links between their status as PWDs and their eligibility to receive help from others.

Although this study was conducted exclusively with people who experience disability, it is completely possible that the (non-disabled) neighbors of the participants were similarly poor in terms of earnings and wealth, and also relied on help for acquiring some of their resources. From casual observation, there did not seem to be a marked difference between the visible material wealth of the families of participants as compared to others in their communities. Despite the possibility of quantifiably similar levels of poverty, the extent to which the participants centered their narratives on the experience of disability gives the impression that it was a meaningful part of their eligibility to receive help from others.

Using the Concept of Help to Inform the Development of Strategies

Help is markedly different than the prominent formally-supported strategies to improve the situation of PWDs in the global South. Prominent strategies in the global South have been influenced by the dominant worldviews of the global North—initially, charitable and medical conceptions of disability during the colonial era,44,45 and more recently, the social model of disability.10,12 These worldviews have informed the development and export of formally-supported strategies such as rehabilitation13,45 and inclusive education.46

At first glance, help might appear to be a strategy responding to a charitable conception of disability, but it diverges from this conception in two important ways:

- Charitable conceptions of disability are typically understood to be imposed upon PWDs by others,44 whereas help responds to a conception of disability to which PWDs are actively contributing.

- The general understanding of charity is that the recipient is passive and disempowered, whereas help seems to reflect fundamentally different socio-economic principles whereby people can engage and exchange respectfully across various levels of wealth status.

The finding that help was the single theme framed by participants to improve their situation calls into question the alignment of the predominant formally-supported strategies with the worldview and priorities of PWDs in Western Zambia. The main value of help as a strategy to improve the situation of PWDs is in its notable departure from the status quo. Help can therefore be used to inform further action in this context, as a set of principles to create new strategies, and as a base of comparison to inform the critique of existing or emerging strategies.

Using Help to Inform Further Action in This Context

This study was developed using participatory research principles whereby a project is intended to generate knowledge and inform practical action.23 With help having been framed as the strategy to improve the situation of the participants, a new challenge has been created: how can the PI effectively operationalize his involvement in help as the practical action resulting from the project? Clues with respect to the approach could be found within the data; specifically, from the example set by the group leaders. Leaders provided some of their own resources to benefit others in the groups, but their primary role has been to seek resources from outside sources. Bruun47 discussed the provision of small amounts of resources to collaborators as a researcher in Zambia, presenting both the challenges and benefits of this practice.

Meanwhile, securing resources from other parties is a role that the PI could be well-placed to fill. Considering the value of the PI to maintain the research relationship with the participants, this ongoing involvement through help can be seen as consistent with Mauss’33 description of an activity that is simultaneously self-interested and disinterested, or Maranz’34 description of asymmetrical reciprocity, or Kaunda’s35 articulation of ways to live together as humanists. An ongoing research relationship of reciprocal benefit challenges the framework in which research ethics are often conceived.48 Yet even in such a partnership of mutual benefit and vulnerability, the structural forces that allow some people to be researchers while others are researched will always carry a threat of exploitative power dynamics that must constantly be recognized and managed.49

Analyzing Components of Help to Inform New Strategies

The characteristics of help could be useful to guide the development of new strategies. One key characteristic of help is that it is based upon a relationship. The relationality of help might seem to conflict with the nature of institutions, yet help shares similarities with formally-supported programs such as peer-support or peer-mentoring. Help diverges from these peer-based programs through its foundation on wealth differences between participants rather than commonalities and its exchange of material resources rather than advice. It is therefore difficult to see how help could be “scaled-up;” however, these could be considerations for practice innovations and future research.

Weaknesses in the Concept of Help. Although participants spoke positively about help in this research, there are foreseeable weaknesses with this strategy. The loss of a helper entails a loss of material support; its success is contingent upon the presence, and continued wealth, of the patrons. Such a strategy could also perpetuate discrimination where social minorities are not chosen to be recipients of help. Conversely, commitments to redressing inequalities on the part of helpers could lead to the creation of different forms of help where resource flow is more reciprocal. Help, as framed here, promotes interdependence over independence and is unconcerned with productivity31 or “sustainability.”50 These qualities are not inherently positive or negative, but could be more or less beneficial depending upon the circumstance.

Constructive Critique of Established or Emerging Strategies

In addition to informing the development of new strategies to improve the situation of PWDs, help can also be used as a base of comparison for formally-supported strategies that are currently prominent in the global South, or at very least in the process of emerging. Through this comparison, it is possible to identify the synergies and the incongruences of these strategies with the accounts of participants.

Rehabilitation as a Strategy. One predominant strategy to improve the situation of PWDs is rehabilitation. Rehabilitation is the first of the “specific programmes and services” recommended in the World Report on Disability1 and was of particular interest to the PI, given his professional background. The field of rehabilitation is one that can be understood in multiple ways (including community-based rehabilitation51) but is nonetheless largely descended from Western biomedicine.13,45 Rehabilitation “aims to enable people with health conditions experiencing or likely to experience disability to achieve and maintain optimal functioning.”1,52 Admittedly, improvements or increases in function could lead poverty alleviation through the mechanism of increased productivity. Participants in this study did refer to reduced function, but typically to justify the need for help, not as a problem requiring a solution in-and-of itself. Although rehabilitation interventions could provide positive outcomes for at least some of the participants in this research, they seem to differ markedly from the way that participants frame a strategy to improve the situation of PWDs.

SCTs as a Strategy. In Zambia, the most prominent formally-supported strategy to improve the situation of PWDs in recent years has been the nationwide introduction of Social Cash Transfers (SCTs).53,54 SCTs are small bi-monthly payments to households that are classified by the Government of Zambia as extremely poor and unable to fully participate in the labor market. Households with PWDs are one of the target groups for SCTs.53 SCTs are similar to help in that they are direct grants of money; however, they are different regarding their regular distribution and depersonalized nature. This government-supported welfare entitlement program could lead to important improvements in the standard of living for the participants in this study and many other PWDs in Zambia, yet a comparison to the co-construction of help reveals some weaknesses and vulnerabilities of this program. As Hansen and Sait55 identified through their anthropological research in South Africa, a depersonalized system can be unresponsive, as community members are confused and angry that the system does not meet their needs. Furthermore, a system of government-issued grants could undermine the culturally-supported and community-minded system of help. This undermining could occur if potential helpers begin to abandon the practice due to the government’s involvement.

Considering the significant experience of poverty of the participants, the distribution of SCTs is undoubtedly a positive strategy to improve the situation of PWDs. In its practice, however, there could be frustration for PWDs who are confused that the system is not amenable to negotiation in situations of greater need. In addition, a discontinuation of SCTs could be very negative for beneficiaries who would lose direct state support, and potentially be without help if potential helpers no longer give.

Research Considerations

There are certain considerations that we would like to acknowledge to better qualify this research. First, the interactional context of the study, in which the PI was a person of privilege relative to the participants, could have stimulated the participants to perform help as potential recipients, making this practice even more visible than it would have been through their descriptions alone. Moreover, although this study was conducted through intercultural dialogue, this report of the study is being delivered in only one of those cultures (the academic and anglophone culture with its roots in the global North). Furthermore, despite our attempts to overcome the pervasiveness of a knowledge system dominated by the global North for disability strategies, this study could also be seen as an expression of knowledge systems from the global North. Our attempts to privilege non-Eurocentric methods and theory were sincere; however, our sincerity does not ensure that these efforts were comprehensive.

In addition, we should note that the results of this study emphasize the commonalities of the study participants rather than their significant diversity. Early in the research design process, we made conscious decisions to prioritize the collective nature of the disability groups. Nonetheless, we were still surprised by the participants’ consistency in referring to help despite their diversity of gender, age, social status, “disability type,” and site (urban and rural). Given this diversity, it is quite possible that sub-group analysis could offer further insights.

Conclusion

Help: an unanticipated rehabilitation strategy worthy of additional attention.

Participants from two groups united by disability in Western Zambia framed strategies to improve their situation as “help.” Help in this local context is understood to be a gift or grant of material resources, shared by a helper with sufficient means to do so and an awareness of a recipient’s need, and is provided based on an expectation of compassion.

Help is different from formally-supported strategies to improve the situation of PWDs in the global South due to its relational nature and its refocus from improving individual function toward a direct focus on poverty alleviation. For the project described here, help could be a mechanism to build relationships and form possible further research-action collaboration. More generally, as a departure from the global North worldview, the principles underlying help could be used to inform strategies appropriate for numerous locations in the global South. Finally, help could be used as a base of comparison from which to consider, critique, and improve the established strategies to improve the situation of PWDs.

Acknowledgements

The authors are extremely grateful for important assistance from colleagues at the Zambia Federation of Disability Organisations (ZAFOD) and the Western Province offices of the Government of Zambia’s Department of Social Welfare. Fieldwork activities were made possible through the contributions of Patrah Kapolesa, Malambo Lastford, Akufuna Nalikena, Chibinda Kashela, and Aongola Mwangala as research assistants. Finally, we would like to thank the reviewers for their thoughtful comments that challenged us to improve this article in important ways.

Funding Sources

Shaun Cleaver was supported by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) Fellowship and a W. Garfield Weston Doctoral Fellowship. Stephanie Nixon was supported by a CIHR New Investigator Award.

Affiliations

Dr. Cleaver: School of Physical and Occupational Therapy, McGill University, Montréal, Québec, Canada; International Centre for Disability and Rehabilitation, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada

Emails: shauncleaver [at] gmail [dot] com (preferable) / shaun [dot] cleaver [at] mail [dot] mcgill [dot] ca (alternate)

Dr. Nixon: Department of Physical Therapy, Rehabilitation Sciences Institute, International Centre for Disability and Rehabilitation, & Dalla Lana School of Public Health, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada

Email: stephanie [dot] nixon [at] utoronto [dot] ca

Dr. Bond: Social Science Unit, ZAMBART, Lusaka, Zambia; Department of Global Health and Development, Faculty of Public Health and Policy, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, London, United Kingdom

Emails: GBond [at] zambart [dot] org [dot] zm / virginia [dot] bond [at] lshtm [dot] ac [dot] uk

Dr. Magalhães: Occupational Therapy Department, Federal University of São Carlos, São Carlos, São Paulo, Brazil

Emails: lmagalhaes [at] ufscar [dot] br / lilianm [at] gmail [dot] com

Dr. Polatajko: Department of Occupational Science and Occupational Therapy & Rehabilitation Sciences Institute, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada

Email: h [dot] polatajko [at] utoronto [dot] ca

Authors’ contributions: Shaun Cleaver was the first author and PhD student conducting the research. Stephanie Nixon, Virginia Bond, Lilian Magalhães, and Helene Polatajko were dissertation committee members who advised the development of the research, its conduct, data analysis, and the writing of this article.

References

- World Health Organization (WHO) and World Bank. World Report on Disability. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2011.

- Eide AH, Nhiwathiwa S, Muderedzi J, Loeb E. Living Conditions among People with Activity Limitations in Zimbabwe: A Representative Regional Survey. Oslo: SINTEF; 2003. Available at: https://www.sintef.no/globalassets/lczimbabwe.pdf. Accessed May 15,

- Eide AH, van Rooy G, Loeb ME. Living Conditions among People with Activity Limitations in Namibia: A Representative, National Study. Oslo: SINTEF; 2003. Available at: https://www.sintef.no/globalassets/lcnamibia.pdf. Accessed May 15, 2019.

- Eide AH, Loeb ME, eds. Living Conditions among People with Activity Limitations in Zambia: A National Representative Study. Oslo: SINTEF; 2006. Available at: https://www.sintef.no/globalassets/upload/helse/levekar-og-tjenester/zambialcweb.pdf. Accessed May 15, 2019.

- Eide AH, Neupane S, Hem K-G. Living Conditions among People with Disability in Nepal. Oslo: SINTEF; 2016. Available at: https://www.sintef.no/globalassets/sintef-teknologi-og-samfunn/rapporter-sintef-ts/sintef-a27656-nepalwebversion.pdf. Accessed May 15, 2019.

- Meekosha H. Decolonising disability: thinking and acting globally. Disabil Soc. 2011;26(6):667-682.

- Grech S, Soldatic K, eds. Disability in the Global South: the Critical Handbook. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2016. Available at: https://www.springer.com/us/book/9783319424866. Accessed May 15, 2019.

- Miles M. International Strategies for Disability-related Work in Developing Countries: Historical, Modern and Critical Reflections. Farsta, Sweden: Independent Living Institute; 2007. Available at: http://www.independentliving.org/docs7/miles200701.html. Accessed May 15, 2019.

- Grech S. Disability, poverty and development: critical reflections on the majority world debate. Disabil Soc. 2009;24(6):771-784.

- Nguyen XT. Critical disability studies at the edge of global development: why do we need to engage with Southern Theory? Can J Disabil Stud. 2018;7.1:1-25.

- Goodley D, Swartz L. The place of disability. In: Grech S, Soldatic K, eds. Disability in the Global South: the Critical Handbook. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2016:69-83. Available at: https://www.springer.com/us/book/9783319424866. Accessed May 15, 2019.

- Meyers S. Global civil society as megaphone or echo chamber?: voice in the international disability rights movement. Int J Polit Cult Soc. 2014;27(4):459-476.

- Kuipers P, Sabuni LP. Community-based rehabilitation and disability-inclusive development: on a winding path to an uncertain destination. In: Grech S, Soldatic K, eds. Disability in the Global South: the Critical Handbook. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2016:453-467. Available at: https://www.springer.com/us/book/9783319424866. Accessed May 15, 2019.

- United Nations. Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. New York: United Nations; 2006. Resolution 60/232.

- Miles M. CBR works best the way local people see it and build it. Asia Pac Disabil Rehabil J. 2003;14(1):86-98.

- Grech S. Recolonising debates or perpetuated coloniality? Decentring the spaces of disability, development and community in the global South. Int J Inclusive Educ. 2011;15(1):87-100.

- what is allyship? why can’t i be an ally? PeerNetBC. Available at: http://www.peernetbc.com/what-is-allyship. Blog posted 2016. Accessed May 15, 2019.

- Smith LT. Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples. 2nd ed. London, UK: Zed Books; 2012.

- Cleaver SR. Postcolonial Encounters with Disability: Exploring Disability and Ways Forward Together with Persons with Disabilities in Western Zambia. [dissertation] Toronto, ON, Canada: University of Toronto; 2016.

- Cleaver S, Magalhães L, Bond V, Nixon S. Exclusion through attempted inclusion: experiences of research with disabled persons’ organisations (DPOs) in Western Zambia. Disabil, CBR Inclusive Develop. 2017;28(4):110-117.

- Cleaver S, Polatajko H, Bond V, Magalhães L, Nixon S. Exploring the concerns of persons with disabilities in Western Zambia. African J Disabil. 2018;7(0):a446.

- Silverman D. Interpreting Qualitative Data: Methods for Analyzing Talk, Text and Interaction. 5th ed. London, UK: SAGE Publications; 2014.

- Herr K, Anderson GL. The Action Research Dissertation: A Guide for Students and Faculty. Thousand Oaks, CA, USA: SAGE Publications; 2005.

- Eakin J, Robertson A, Poland B, Coburn D, Edwards R. Towards a critical social science perspective on health promotion research. Health Promot Int. 1996;11(2):157-165.

- Central Statistical Office. Zambia 2010 Census of Population and Housing, National Analytical Report. Lusaka, Zambia: Central Statistical Office; 2012. Available at: http:// http://catalog.ihsn.org/index.php/catalog/4124/related-materials. Accessed May 15, 2019.

- Kumaran KP. Role of self-help groups in promoting inclusion and rights of persons with disabilities. Disabil, CBR Inclusive Develop. 2011;22(2):105-113.

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualita Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77-102.

- Braun V, Clarke V. What can “thematic analysis” offer health and wellbeing researchers? Int J Qualita Stud Health Well-being. 2014;9:26152.

- Canadian Coalition for Global Health Research. CCGHR Principles for Global Health Research. Ottawa: Canadian Coalition for Global Health Research; 2015. Available at: http://www.ccghr.ca/resources/principles-global-health-research. Accessed May 15, 2019.

- Cleaver S, Magalhães L, Bond V, Polatajko H, Nixon S. Research principles and research experiences: critical reflection on conducting a PhD dissertation on global health and disability. Disabil Global South. 2016;3(2):1022-1043.

- Cleaver S, Magalhães L. Unanticipated productivity: using reflexivity to reveal latent assumptions and ideologies in postcolonial disability research. Cogent Social Sciences. 2018;4:1466620.

- Makeke. In: Barotseland.net. Online Silozi-English Dictionary. Available at: http://www.barotseland.net/sil-eng2a.htm. Accessed May 15, 2019.

- Mauss M. The Gift: The Form for Exchange in Archaic Societies. Halls WD, trans. London, UK: Routledge; 1990[1950].

- Maranz D. African Friends and Money Matters. Dallas, TX, USA: SIL International;

- Kaunda KD, Morris CM. A Humanist in Africa: Letters to Colin M. Morris. London, UK: Longmans; 1966.

- Kowalski R. The gift–Marcel Mauss and international aid. J Comp Soc Welfare. 2011;27(3):189-205.

- Douglas M. Foreword: no free gifts. In: Mauss M. The Gift: The Form for Exchange in Archaic Societies. London, UK: Routledge; 1990:vii-xviii.

- Godbout JT, Caillé World of the Gift. Winkler D, trans. Montreal, QC, Canada: McGill-Queen’s University Press; 1998.

- Komter AE. Social Solidarity and the Gift. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2005.

- Stirrat RL, Henkel H. The development gift: the problem of reciprocity in the NGO world. Ann Am Acad Political Soc Sci. 1997;554:66-80.

- Rafapa The representation of African humanism in the narrative writings of Es’kia Mphahlele. [dissertation]. Stellenbosch, South Africa: University of Stellenbosch; 2005.

- Zulu JB. Zambian Humanism: Some Major Spiritual and Economic Challenges. Lusaka, Zambia: National Education Company of Zambia;1970.

- Meebelo HS. Main Currents of Zambian Humanist Thought. Lusaka, Zambia: Oxford University Press;1973.

- Beresford P. Poverty and disabled people: challenging dominant debates and policies. Disabil Soc. 1996;11(4):553-568.

- Ingstad, B. 2001. Disability in the developing world. In: Albrecht GL, Seelman KD, Bury M, eds. Handbook of Disability Studies. Thousand Oaks, CA, USA: SAGE Publications. 2001:219–251.

- Schuelka MJ. Constructing a modern disability identity. In: Azzopardi A, ed. Youth: Responding to Lives. Rotterdam, Netherlands: Sense Publishers. 2013:137-151.

- Bruun B. Daily Trials: Lay Engagement in Transnational Medical Research Projects in Lusaka, Zambia. [dissertation]. London, UK: London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine; 2014.

- Benatar SR. Reflections and recommendations on research ethics in developing countries. Soc Sci Med. 2002;54(7):1131-1141.

- Wallerstein NB, Duran B. Using community-based participatory research to address health disparities. Health Promot Pract. 2006;7(3):312-323.

- Swidler A, Watkins SC. “Teach a man to fish”: the sustainability doctrine and its social consequences. World Develop. 2009;37(7):1182-1196.

- Khasnabis C, Motsch KH. Community-based Rehabilitation: CBR Guidelines. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2010.

- Stucki G, Cieza A, Melvin J. The international classification of functioning, disability and health: a unifying model for the conceptual description of the rehabilitation strategy. J Rehabil Med. 2007;39(4):279-285.

- Ministry of Community Development, Mother and Child Health. Harmonised Manual of Operations, Social Cash Transfer Scheme. Lusaka, Zambia: Department of Social Welfare; 2013.

- Arruda P, Dubois L. A Brief History of Zambia’s Social Cash Transfer Programme. Brasilia: International Policy Centre for Inclusive Growth; 2018. Available at: https://www.ipc-undp.org/pub/eng/PRB62_A_brief_history_of_Zambia_s_social_cash_transfer_programme.pdf. Accessed May 15, 2019.

- Hansen C, Sait W. “We too are disabled”: disability grants and poverty politics in rural South Africa. In: Eide AH, Ingstad B, eds. Disability and Poverty: A Global Challenge. Bristol, UK: The Policy Press; 2011:93-117.

Member since 2019 | JM14274

Member since 2019 | JM14274

NO COMMENT