Historical Perspectives in Art | Edgar Degas: Celebrating Beauty in Movement

By Melissa McCune, SPT

Edgar Degas (1834–1917) grew up in Paris during an exceptionally extraordinary time for art and literature. That, combined with his natural talent for observation, and his affluent up-bringing as the son of a successful banker, gave Degas all the necessary qualities to form himself into a renowned classical artist. However, he was a renegade: Degas was known for bending the rules of his classical training to render both bold and subtle movements of the human body in unique and exciting ways.

Throughout his twenties, Degas was drawn to and trained in the classics, studying at the Ecole des Beaux Arts in Paris and later traveling to Italy where he spent years refining his draftsmanship.1 During this time, he focused on historical subjects with clear, defined lines as was common with his traditional training. It wasn’t until 1862, when Degas was introduced to the Impressionist style by the artist Edouard Manet, that his interest in portraying individuals in their everyday life began to take root.1

The Impressionist movement was just beginning in Paris and was a means to turn away from the traditional take on the sharp details of realism, focusing more on light and loose brushstrokes to capture the fleeting moment of a scene. 2 Although Degas was inspired by the Impressionist style, he preferred not to be defined by a particular art movement.2 Rather, he simply made art that was solely and uniquely his own, without conforming to the expectations of the world around him.

Montmartre and Ballet

Taking advantage of his financial freedoms, Degas moved into the Parisian district of Montmartre—a unique environment where people from all walks of life lived and worked alongside each other, and artists like Degas drew inspiration from the bohemian way of life around him.1 It was here that Degas was exposed to the world of ballet; first as a member of the audience, then later as an artist at work. Capturing the human body in truly remarkable and innovative ways, Degas was drawn to the ballet, where he was able to closely observe the beauty and intricacies of a body in motion. Degas focused on a unique perspective of the ballet, revealing the connection between dance, science, and anatomy in his works. He made nearly 1,500 works focusing on ballet dancers in the late 19th and early 20th centuries2—all celebrating the abilities of the human body and the care and attention it required to perform at its best.

The Beauty of Movement Captured

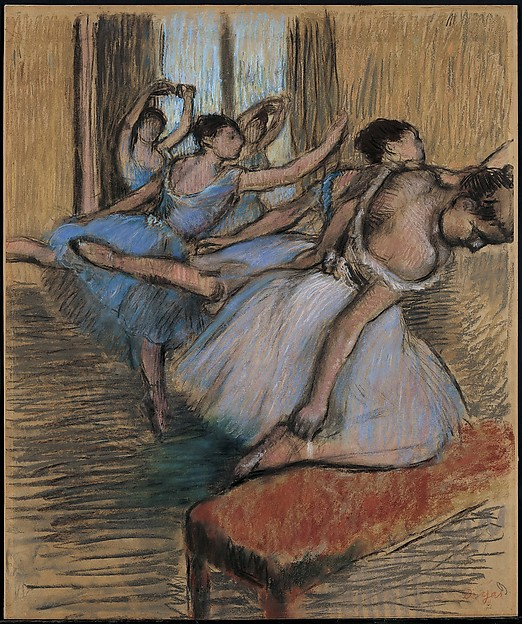

In The Dancers (c.1900) (Fig.1), Degas portrays figures balancing gracefully on a single leg, using laws of physics to produce and sustain motion, and illustrating the precise placement of even the most distal phalanx as critical factors in capturing movement in art.

Figure 1. Edgar Degas. The Dancers. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Image Credit: H. O. Havemeyer Collection, Bequest of Mrs. H. O. Havemeyer, 1929.

In Dancers Practicing at the Barre (1877) (Fig. 2), Degas uses an off-centered composition and unusual perspectives of the human body to depict flexibility, posture, and balance.

In both of these works, the focus is not on the ballerina’s outfit or facial features; rather, Degas chose to focus his work on the body as a whole to reveal its objective beauty and intimate connection with the space around it.

Figure 2. Edgar Degas. Dancers Practicing at the Barre. 1877. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Image Credit: H. O. Havemeyer Collection, Bequest of Mrs. H. O. Havemeyer, 1929.

While Degas often concentrated on the technical side of the ballet and the human body, he also painted many “behind the scenes” moments that captured the ballerinas meandering about during practice or stretching backstage before a performance—presenting subtle and more subdued anatomical movements.

A later work, Dancers, Pink and Green (1890) (Fig. 3) is an example of this nuanced movement of the human body, stripping away the elegant cultural façade of the ballet and exposing the simple and beautiful foundation of the dance.

Figure 3. Edgar Degas. Dancers, Pink and Green. 1890. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Image Credit: H. O. Havemeyer Collection, Bequest of Mrs. H. O. Havemeyer, 1929.

With deteriorating vision, Degas became somewhat of a recluse in the later years of his life, spending time in his studio apartment in Montmartre continuing to make paintings, drawings, and wax sculptures. Unsurprisingly, though, he never strayed too far from the ballet.

Degas, Little Dancer, Aged Fourteen (Fig. 4) was created as a wax sculpture, later to be cast in bronze after his death in 1917. The figure depicts the essence of classical ballet at the time: shoulders held low and head held high.1

The Therapeutic Art of Dance

It’s clear that dance, whether observed in the moment or transcribed onto paper via graphite and paint, is objectively beautiful to both the trained and untrained eye. However, in the spirit of humanities and rehabilitation, it’s important to point out that the art of dance can also be therapeutic. There is tremendous power in letting the body be completely free and unhinged, moving subconsciously through music and liberating it from the grasp of societal norms.

The New York City Ballet, a powerhouse in the world of dance, leans into this idea with their workshops geared toward children who simply love to dance, regardless of their physical abilities.3 The creation of Access Programs through the New York City Ballet has facilitated inclusion in dance while helping children and adults with disabilities unlock their potential and experience the art of ballet.3,4

Degas’ work provides a sense of freedom about the human body and its capabilities. From technical positions to simple tasks, Degas’ dancers show us that when we are fully present in our bodies, beauty ensues. This can be a crucial concept for individuals with limited control or movement of their bodies; rehabilitation professionals who are able to relay this concept to patients will be helping to redefine common ideas about what makes a movement beautiful.

The Body Redefined

Throughout his life, Edgar Degas proved to be more than just the sum of his father’s wealth and his extensive classical training. He redefined how individuals perceive the human body and captured the fleeting moments that were often missed, marking them with paint and color to show the world their lasting beauty.

References

- Tractman, Paul. Degas and His Dancers.Smithsonian Magazine. April 2003. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/degas-and-his-dancers-79455990/. Accessed June 29, 2018.

- Schenkel, Ruth. Edgar Degas (1834 -1917): Painting and Drawing. The Metropolitan Museum of Art.October 2004. https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/dgsp/hd_dgsp.htm. Accessed June 29, 2018.

- Access Programs. New York City Ballet.https://www.nycballet.com/accessprograms.aspx.Accessed July 16, 2018.

- Mordicai, Adam. A Mom Wrote a Letter to the NYC BalletAbout her Daughter’s Disability. They Responded Gracefully. Upworthy. Cloud Tiger Media, Inc. July 6, 2015. https://www.upworthy.com/a-mom-wrote-a-letter-to-the-nyc-ballet-about-her-daughters-disability-they-responded-gracefully. Accessed July 15, 2018.

Member since 2019 | JM14274

Member since 2019 | JM14274

NO COMMENT