Inside "Christina's World"

By J.O. Ballard, MD

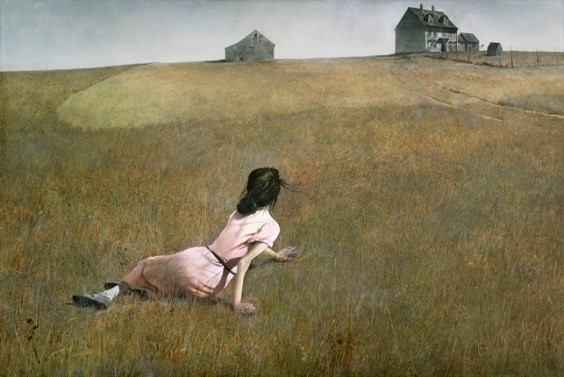

Recently, 10 fourth-year Penn State medical students gathered for a humanities seminar course on the art of observation. The class began with a challenge to examine Andrew Wyeth’s painting Christina’s World for 30 seconds, observing as many details as possible, then to look away and sketch on paper all they could remember. Most of them drew the landscape—an expansive grassy field with a distant farmhouse, barn, and outhouse perched at the upper edge of the painting. One student remembered a flock of birds flying near the barn; others drew stick figures of a woman on the ground crawling in the direction of the house.

Like forensic detectives, the class returned to examining the painting for clues, first describing the mood Wyeth creates, using adjectives such as “mysterious,” “isolated,” “lonely,” and “foreboding.” They wanted to know more. Who is this woman whose faded pink dress is highlighted by sunlight? Why is she alone in the field, and what brought her to this place? Why must she crawl, propelling herself with her arms while her legs appear useless? Who lives in the house on the hillside? Through eyes of soon-to-become physicians they identified signs of a chronic disease—weak legs, wasted arms, and contorted, knobby hands. Despite her apparent physical limitations, this woman appears resolved to reach the farmstead using every ounce of strength she possesses.

Figure 1: Andrew Wyeth, Christina’s World, 1948, tempera. Museum of Modern Art, New York, ©Artist Rights Society (ARS), Image permission: Art Resource, NY.

In this familiar American painting, Wyeth’s love of coastal Maine merges with his enduring platonic relationship with Christina Olson, who lived a lifetime in the weathered house depicted in this iconic image. The original structure was built around 1790 in the small seaside town of Cushing by Christina’s distant relative, Samuel Hathorn II. In 1920 Wyeth’s father, the well-known illustrator N.C. Wyeth, purchased a sea captain’s house in the nearby village of Port Clyde to which his family returned each summer from their home in Chadds Ford, PA.1

Artist and Subject

On July 12, 1939—Andrew Wyeth’s 22nd birthday—he first met his future wife Betsy James, the daughter of an artist friend who also summered in Cushing. During a drive around the area, they stopped at the Olson house where Betsy introduced him to her friend Christina. From the beginning, Wyeth was emotionally drawn to Christina and her brother Alvaro and the “fierce independence” with which they lived in the face of Christina’s progressive physical disability.1

Christina’s neurologic disorder caused a “clumsy, waddling gait” and a tendency to fall beginning early in childhood. She refused medical evaluation most of her life, always insisting that she was “lame not crippled.”2 By the age of 26, deteriorating muscle strength and fatigue limited her ability to walk more than a few steps without support. At her family’s insistence she finally agreed to allow consultation at Boston City Hospital in March 1919. However, after her one-week hospitalization, the specialist was unable to make a specific diagnosis. His disheartening advice was for her to keep living as she had in the past.2(p7) In retrospect, based on a study of photographs and recorded descriptions of the course and nature of her disability, it seems likely that she suffered from Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease, a hereditary disorder that over time causes progressive muscle deterioration and diminished sensation.2(p9)

By age 50 Christina Olson navigated around the property by crawling, primarily using the strength of her shoulders and hips. In the last years of her life she was confined to the first floor of her home due to her progressive weakness. Although she could not perform most household duties, she continued to take responsibility for the cooking. She would “hitch” her favorite kitchen chair, scooting around the room between the wood-burning stove and the table where she stored cooking ingredients for her famous baked goods.3 She occasionally sustained burns on her extremities because of her inability to sense the heat from her stove.2(p8)

Wyeth’s almost daily summer visits to the Olson House began with coffee and banter with Christina and Alvaro “about the minutiae of their circumscribed life.”3(p10) He was fascinated by the house with its dust and cobweb-covered keepsakes, sea shells, layers of soot, and peeling wallpaper.3(p11) Wyeth used the house as the subject or setting for roughly 300 of his drawings and paintings.1(p21) He once remarked about the house that “(t)here’s a haunting feeling there of people coming back to a place.”3(p12)

Trust

The trusting relationship that Christina, Alvaro, and Wyeth shared made it possible for the artist to roam freely about the property and set up a studio in an empty room on the third floor. Wyeth spent hours painting, but also “dreaming”—the term he used to describe a state of mind that allowed his imagination to “open to a web of associations and recollections.”3(p15)

Wyeth ultimately completed four paintings of Christina. In the first one, titled Christina Olson (1947) (Figure 2), she sits alone in a doorway surveying the landscape. Wyeth biographer Richard Meryman noted that the artist described this painting as Christina “looking out to sea ‘like a wounded gull.’”3(p20) A shaft of sunlight catches a profile of her rugged face, simple black dress, and atrophied forearms and hands. She appears still and perhaps vulnerable, but nonetheless reconciled to her place in life.

Figure 2: Andrew Wyeth, Christina Olson, 1947, tempera. Myron Kunin Collection of American Art. Minneapolis, Minnesota, © 2017 Andrew Wyeth/Artist Rights Society (ARS)

Wyeth’s third-floor studio window in the Olson home afforded an unobstructed view of the field in front of the house and the cove beyond. The inspiration for several of Wyeth’s paintings came to him while viewing the world through this window. In May 1948, he glanced out and noticed Christina dragging her body across the field as she was returning from gathering flowers for house decorations.1(p24) Richard Meryman wrote of this scene, noting that, “(t)he apparition of Christina, ‘crawling like a crab on a New England shore,’ stirred his imagination.”3(p7) Later that evening during dinner with his wife and parents, the idea for Christina’s World crystallized in Wyeth’s mind; he excused himself to make a hasty pencil sketch of the concept.3(p8)

He worked on Christina’s World throughout the summer of 1948, convincing Christina to pose for him in the field. Although Wyeth skillfully drew her wasted arms and distorted hands, he chose to substitute images of his wife Betsy’s torso and his Aunt Elizabeth’s hair.3(p20) He placed the image of Christina farther away from the house, down the hill near the Olson family burial site,3(p8) perhaps to symbolize the depth of her emotional strength and determination in life.

The finished painting was hung on the wall above the sofa in the Wyeth cottage in September 1948. At dinner one evening Wyeth summoned up the courage to ask Christina how she liked it. She gave it her blessing by drawing his fingers to her lips.3(pp21-22) However, Wyeth was disappointed with it, and according to Meryman, believed it was “a complete flat tire.”3(p22) The public did not share this assessment. In rapid succession, the painting was purchased by the Macbeth Gallery in New York and, by December 1948, acquired by the Museum of Modern Art,3(p22) where it is currently viewed by millions of visitors each year. Today, Christina’s World is widely recognized as one of America’s most treasured works of art.

Empathy

A student in our humanities seminar asked the reason for Wyeth’s obsession with Christina and her world. Mackowiak draws attention to the fact that Wyeth’s empathy for Christina may have been influenced by his own physical disability—a hip malformation that had prevented him from running and made him feel like “an outsider” as a child.4 Meryman, taking an over-arching view, suggests the driving force of Wyeth’s artistic genius was a “tenderness for unappreciated people reduced by life—his reverence for self-sufficiency and perseverance.”3(p14) Perhaps Andrew Wyeth’s own words best sum up his romance with Christina’s world:

“I’ve seen Olson’s from the air on the way back by plane to Pennsylvania—that little square of the house, dry, magical—and I think, My God, that fabulous person. There she is, sitting there. She’s like a queen ruling all of Cushing. She’s everybody’s conscience. I honestly did not pick her out to do because she was a cripple. It was the dignity of Christina Olson. The dignity of this lady.”3(p13)

Wyeth’s 30-year friendship with the Olsons continued uninterrupted until Alvaro and Christina died one month apart in December 1967 and January 1968, respectively.1(p24)

The Art of Medicine

The study of medicine requires the acquisition of scientific knowledge and of the skills of listening to the patient’s complaints and observing characteristic physical findings and laboratory data in order to make a specific diagnosis. The art of medicine involves something more—the development of an empathic understanding of the patient’s lived experience of illness. By analyzing and understanding the context of works of art such as Christina’s World, medical students learn to sharpen observational skills and heighten empathic awareness.

References

- Komanecky M, Nakamura O. Andrew Wyeth, Christina’s World and the Olson House. Rockland, ME: Farnsworth Art Museum (in conjunction with Skira Rizzoli Publications, Inc., New York, NY); 2011:22-23.

- Anderson R. Christina’s World: American icon and medical enigma. Pharos. 2007(Summer);70:6-7.

- Meryman R. Andrew Wyeth:A Secret Life. New York, NY: HarperCollins; 1996:8-10.

Member since 2019 | JM14274

Member since 2019 | JM14274

NO COMMENT