Bedside Audio Storytelling for Hospital Patients: A Program Overview

By Ami Walsh, Jeffrey E. Evans, Elaine Sims, Robin Lily Goldberg, Kimberly L. Peters, Katherine Globerson, Claudia Drossel, Stefanie Blain-Moraes, and Nancy K. Merbitz

Introduction

For many of us, to be a patient in the hospital is a unique, disorienting experience. The pain from an illness, accident or disability can be overwhelming. Our sense of self may be challenged by an unfamiliar place where we are known chiefly by our diagnoses and symptoms. Personality, likes and dislikes, life history (aside from health), are often beside the point – because the purpose of being a patient is for healthcare professionals to treat a particular disease or injury. Of course getting treatment and getting well are everyone’s aim. However, for some patients, not being known for who they are can place them at an uncomfortable remove from the very health system and professionals whose help, at that moment, is most urgently needed. Sometimes emotional complications ensue, from dysphoria and depression to sleep or appetite loss, and even poor cooperation with vital treatments and recommendations. Particularly vulnerable are patients with longer lengths of stay away from home or who have few or no opportunities to communicate with friends or loved ones. Even a short hospitalization with few expressive outlets can challenge one’s sense of self.1 Prior to treatment on acute or rehabilitation units, some patients have experienced critical illness and extended periods of immobility and sedation in an ICU, with potentially profound impacts on personal meaning-making.2

Bedside arts as a means of self-expression and retaining identity can provide relief, at least temporarily, and are a feature of a growing number of larger hospitals.3,4 At Michigan Medicine (University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI), bedside music, visual arts, and now our audio storytelling program are routinely offered through the hospital’s Gifts of Art (GOA) program, which brings the power of art and music into the healthcare environment. Its programs are intended to calm and comfort patients, visitors, and staff, and support the healing process. Art and music enhance public spaces in the hospital, while a variety of bedside programs deliver the arts in a more focused and intimate setting.

Although some hospitals support expressive writing activities for patients and caregivers, patient-centered audio storytelling programs are relatively new.5 Like “StoryCorps,” heard regularly on National Public Radio, our program enables individuals who might not otherwise record a story to do so. Working with a facilitator, patients have the opportunity to record an audio story for a loved one, or for anyone they choose, during a single recording session in their hospital room. The collaboration between patient and facilitator typically takes 90 minutes, concluding with participants receiving the edited audio piece on a CD at no charge. All audio stories are confidential and shared only with expressed written consent. Since we began our program, more than 110 patients have recorded audio stories, and a few have recorded more than one.

This article describes how our program started, the institutional oversight that supports it, how patients become involved, and the collaborative process between patient and facilitator by which stories are evoked and recorded. Virtually all patients have given permission for their stories to be used for educational purposes, and five have consented to publish their recordings as a part of this report. Hearing their voices is a rewarding listening experience; we are grateful they and their families have allowed us to share their stories with the readers of this journal.

Along with our program methodology, we present findings from follow-up interviews with 55 participants on how recording a personal story affected them. We will discuss how the bedside storytelling experience may restore an orienting sense of self for some patients, even before they return home.

Program Beginnings

Narrative art interventions are best known as offering opportunities for creative self-expression through the act of writing, as pioneered by social psychologist Dr. James Pennebaker.5 He and others have shown that, depending on the population, “expressive writing” can produce tangible mental and even physical health benefits (Note 1).7-9 In the hospital setting, however, not all patients can or want to write. Fatigue, tremors, disability, and physical post-operative limitations are just a few reasons writing isn’t possible or tolerable for many patients. With audio recording tools increasingly accessible and affordable, we saw an opportunity to use digital technology to create a new and potentially more inclusive approach for patients who wished to create personal stories.

Implementing our program took months of planning. First, we had to ensure our audio recording facilitator had proper training to work with hospital patients. Ami Walsh, a creative writing teacher with an MFA in fiction, had previously led digital storytelling workshops for pediatric patients in a non-hospital setting. Elaine Sims, director of Michigan Medicine’s GOA program, oversaw the training process. Founded in 1986, GOA is one of the country’s oldest and most comprehensive arts-in-healthcare programs, and has been recognized by the National Endowment for the Arts as a best-practice model program.15 Areas of training for the facilitator included patient-care environment orientation, infection control, disinfecting procedures, HIPAA compliance, hospital safety and security protocols, and shadowing sessions with an experienced bedside artist. Rehabilitation Psychology and Neuropsychology clinician Dr. Jeffrey Evans provided clinical consultation as needed. Being a member of the inpatient team with Michigan Medicine’s Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation service for more than 25 years gave Evans insight into patients’ needs for social connection and challenges to self-concept (Note 2). Evans was also an early source of patient referrals and, together with Sims, reviewed Walsh’s weekly reports summarizing patient interactions. Prior to meeting with patients, our team defined a clear program mission: to provide expressive storytelling activities at the bedside that honor the patient’s sense of self, offer comfort and hope, and support a hospital experience that dignifies the individual. Finally, we named our new program “Story Studio.”

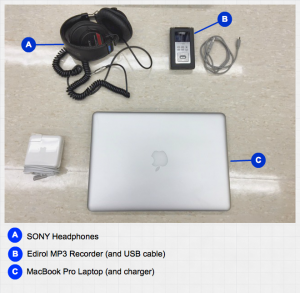

Figure 1a: Audio hardware

By January 2012, we were ready to introduce Story Studio to adult patients at University Hospital, the main care center at Michigan Medicine with nearly 1,000 beds. Storytelling equipment included audio recording hardware and software (Edirol MP3 recorder, SONY headphones, a MacBook laptop with GarageBand for sound editing, a LogiTech laptop speaker, and blank CDs with designed labels and sleeves). An ergonomic supply cart enabled the facilitator to easily transport recording equipment around the 11-story hospital (Figures 1a-c).

Patients were immediately interested in Story Studio – including those who did not consider themselves storytellers, writers, or even “creative.” For six months, from January through June, the facilitator, who worked at the hospital every Thursday evening (a schedule that accommodated her day job), recorded stories with 22 patients, an average of one every week. The stories were not principally about the patient’s illness, disease, or accident, but about the people they loved, and the pursuits and passions that gave them comfort and pleasure and defined who they were. While the material for a story was open-ended, the intention behind telling it was not; we feel that this made all the difference. Specifically, one of the first questions the facilitator asked patients after introducing herself was, “Is there someone you’d like to give a story to?” The moment the patient imagined a listener who mattered, what they wanted to say often came quickly into focus with help from our facilitator. Most patients recorded personal narratives, often expressing feelings of love and gratitude, and organized around defining moments in their lives: births and deaths; choices they made or didn’t make to pursue passions, talents, dreams; encounters with misfortune and joy.

Figure 1c: CDs

Figure 1b: Supply cart

At the start of our program, we were surprised by the ease with which patients sustained their focus on the recording activity and spoke with an emotional intensity and openness that seemed to also surprise them. Reflecting on her experiences working with patients from January to June 2012, during the program’s first six months, Walsh wrote:

The patients I met with did not make false starts, turn down blind alleys, or deliberate over this or that word. It was as if they’d already gone through some sort of narrative apprenticeship and were relying on instinct and intuition to create stories that felt satisfying and whole….“I just dug in there and found what I wanted to let her know,” one patient told me after recording a story for his wife. He captured what I witnessed again and again: Men and women, husbands and wives, sons and daughters, digging down deep to find something essential they wanted to say to the people they loved.

Based on the success of our first year, we began an Institutional Review Board (IRB)-approved research project that included patient follow-up interviews to evaluate our storytelling program and its impact on participants. At the same time, we also sought to clearly document our patient-facilitator approach so that our program might serve as a model for other hospitals and healthcare centers interested in starting a bedside audio storytelling program. We will describe our facilitation approach first, then review some findings from our patient interviews.

Our Collaborative Patient-Facilitator Approach

Our facilitation approach involves a step-by-step process of identifying, engaging, and forming a creative collaboration with patients.

Patient Referrals. Gifts of Art bedside musicians and visual artists as well as nurses and other clinical staff provide referrals. Common reasons range from staff members knowing that a patient may be bored, lonely, separated from family, looking for an art-making distraction, or is simply talkative and likes to share personal stories. On occasion, referrals are made on behalf of patients leaving the hospital for hospice care.

We’ve discovered, anecdotally, that patients are more likely to participate in Story Studio if they have had prior experience with one of the hospital’s bedside musicians or visual artists; rates of participation are lower if patients are aware that their psychologist or physician has referred them. This may suggest, at least for the somewhat self-selecting group of patients who respond to our facilitator’s explicit invitation to record a story as a “gift,” that the desire to participate resides in an expressive rather than therapeutic need, and that it is a personal decision rather than a response to a prescription.

The Setting and Opening Invitation. Our facilitator meets with patients in the evening, when the bustle of the hospital day is winding down and the halls are generally quiet. The secluded setting (the patient’s room) and twilight hour (a traditional time for bedside stories) seems ideally suited for a storytelling activity. Patients are often alone in their rooms and lying down, resting or watching TV. When the facilitator introduces herself, she mentions the referring staff member and identifies herself as a writer-in-residence with the hospital’s Gifts of Art program. She provides a general orientation about the storytelling activity and explains her role as a facilitator before asking directly if the patient would like to record a story.

If patients are interested, they will ask questions (How long does it take? What if I’m not sure what to say? What if I don’t like the way I sound?). If they appear indifferent, tired, or in any kind of distress, the facilitator never tries to “sell” the activity. She stresses that participation is entirely voluntary and declining will not offend anyone. She may also need to clarify that the storytelling program is not collecting testimonials for the hospital’s marketing purposes, or for a research agenda, or even as part of the patient’s clinical care. It is a bedside arts service, offered at no cost, and any recording the patient makes is exclusively for the patient’s selected listeners. Patients can choose to keep their stories private or, as some of our participants have elected to do, share it with friends and family on social media or broadcast it over a sound system as part of a church service or community event. GOA keeps a confidential copy on the hospital’s servers and can retrieve the file, with the patient’s authorization, if the original gets lost or damaged. How long a recording session takes depends on the length of the story the patient wants to record. Typically, patients spend from 30 to 45 minutes working with the facilitator to record their story and then select an instrumental track to mix into the background, if desired. The facilitator leaves the room to edit the file and then returns to review it with the patient. Together, they listen to the piece and make any final edits before the facilitator burns the file to a CD or transfers it to the patient’s personal laptop via a flash drive. From start to finish, the activity takes about 90 minutes.

About one out of every five patients introduced to Story Studio expresses an interest in participating. Of those who say yes, half ask the facilitator to return the following week, after they’ve had time to think about what they’d like to record, and half begin working immediately with the facilitator. Many participants say they opt not to wait because they may be discharged from the hospital before the facilitator can return and they see this as their only opportunity to record a story.

Preparation for Recording. As we said earlier, the moment patients imagine a listener who matters to them, what they want to say—the story material—often comes quickly into focus with help from the facilitator, who asks a series of focusing questions. There is no prescribed list of questions. Instead, our facilitator employs a novel approach by “inhabiting” the perspective of whomever the patient has selected as his or her audience. That perspective becomes the facilitator’s guide in exploring narrative possibilities with the patient. For example, if a patient says he’d like to record a story for his school-aged granddaughters, the facilitator will ask questions about what sorts of stories those girls might like to hear. Perhaps an adventure about their grandfather when he was a boy? Or a story that celebrates an adventure they experienced with him? The facilitator closely follows the patient’s responses, drawing from the inventory of what’s been said to inform the next question. The patient may say his granddaughters play soccer just as he once did, which opens a door to more questions about, say, their shared joy for the game or details about an especially memorable season or contest. In this way, the conversation is ultimately guided by the patient’s interests and memories, and not by the facilitator.

Typically, after responding to a few questions, patients discover material for their story. We’ve been surprised at how quickly this happens. When it does, patients become visibly alert with a sense of purpose. They may elevate the head of their hospital bed or turn off the TV and ask the facilitator to step into their room, even to take a seat. As the patient and facilitator continue to discuss story possibilities together, the facilitator’s primary role is to help patients feel confident and capable in their ability to transform their ideas into a presentable audio recording.

One chief way the facilitator does this is by calling attention to the narrative elements inherent in the patient’s material while exploring a structure for it. The facilitator might highlight memories or associations the patient has shared that create a narrative arc with a beginning, middle, and end. If the material doesn’t suggest linear time as a way to arrange the story, she might call attention to other organizing elements and ways to shape the material, such as the possibility for a list poem, a letter, or a song. She will also look for opportunities to praise the patient’s specificity of the detail, sensory descriptions, images, or metaphors. By deliberately naming techniques practiced storytellers use to think about, and hone, their craft, the facilitator does two things: She signals her narrative expertise, helping to build trust with patients for the creative endeavor they are about to undertake. More importantly, she invites patients to assume an active role in shaping and arranging their own stories. As a result, patients may see themselves as well as their stories from a fresh perspective, one that imparts a sense of authorial control and encourages them to tell a story in ways they never have before. The patient is at once performing, in a sense, for an intimate known audience (the selected listeners), a relative stranger (the facilitator), as well as other implied potential audiences invited into the room by virtue of the recorder—a technology that transforms speech into a recording that can be preserved for future generations. The presence of listeners, seen and unseen, gives the recording session a palpable charge. One patient, who made a nearly hour-long autobiographical recording about her life, described her experience this way:

“These thoughts have been swirling around for so long in here,” she said, touching her head. “And also”—she tapped a spot above her heart—“in here…I feel a sense of relief having gotten my story out to someone other than someone in my family—having gotten it out, period. I think that if I had stood before my family to give it to them, they would think, ‘Oh, we’ve heard it before.’”

Patients may not know exactly what they are going to say when the recorder is turned on (just as the facilitator doesn’t), but they now have enough confidence in the possibilities – and in their abilities – to be ready to start recording. (Occasionally, a patient will feel more comfortable creating a script to read during the recording, one he or she writes longhand or dictates to the facilitator.) When initial uncertainty gives way to excitement, the facilitator transitions with the patient from talking about the story to recording it.

Recording the Story. To prevent patients who are seriously ill from exhausting themselves before the recorder is turned on, the facilitator suggests that they not rehearse their piece; instead, she reminds them to conserve their energy for their most important audience, their listeners.

Once the patient is ready to start recording, the facilitator collects her equipment from her cart in the hallway, disinfecting the recorder and headphones before re-entering the room. To help patients feel at ease, she presents the recorder and headphones and answers any questions about the equipment. She explains to the patient, somewhat apologetically, that it’s necessary for her to hold the mic very close to get a good audio level. She demonstrates by moving the recorder about 6 to 10 inches from the patient’s mouth and makes sure that the patient is comfortable with this closeness. At the same time, the facilitator also gauges the patient’s desire for eye contact. Since it’s important for the facilitator to refrain from verbal encouragement during the recording (if her voice overlaps with the patient’s, it can’t be edited out), she relies on facial cues. Some patients welcome this and want constant support when they are recording, while others do not—in fact, they will create a space of privacy by looking away or closing their eyes.

Figure 2: Bedside Recording Session. Photo credit: Gregory Maxwell

The facilitator puts on the headphones and asks the patient to say a few words, listening for competing sounds in the room or out in the hall. Adjustments can be made to minimize audio distractions (such as closing the door or asking patients in the adjoining space to speak more softly) but, of course, this isn’t always possible. While a single or double hospital room is not an optimal sound studio—for example, it may not be possible to silence beeping machines, hisses from oxygen tubes, voices from the other side of the room or out in the hall—it is a private and even sacred space, transformed by the opportunity to create, and one that seems to make participants feel safe recording intimate stories (Figure 2).

Editing the Audio File. When the patient has finished recording a story, the facilitator will ask if he or she wants to mix in any background music. Most patients want this option, and they can select from a library of instrumental tracks organized by genres ranging from classical, country, and rap to blues, jazz, rock, and others (Note 3). Before the facilitator leaves to edit and mix the audio, she asks the patient for a title. If one doesn’t come to mind, they’ll wait until they hear the edited piece.

Audio editing is done outside the patient’s room and takes from 30 to 60 minutes. The file is transferred from the recorder to a MacBook laptop and edited in GarageBand. With few exceptions, every audio story is recorded in a single take and lightly edited. The facilitator trims out “ums” and “ahs,” coughs, and other distracting sounds, while also taking care not to make any changes that significantly alter the original recording. Changes in pacing, rhythm, pauses, silences—these moments often hold as much meaning as the spoken word, and the facilitator looks to preserve them. If the patient has selected music, the file is copied into a second track. The voice and music levels are mixed and levels adjusted so the music complements but does not compete with the voice. A standard opening begins with a brief musical intro (four to six seconds) before the voice comes in. Throughout the rest of the recording, the music levels are kept low and generally remain in the background. If the patient’s recording has abrupt transitions or unnatural breaks, the music can be used to create a bridge from one section to the next (Note 4).

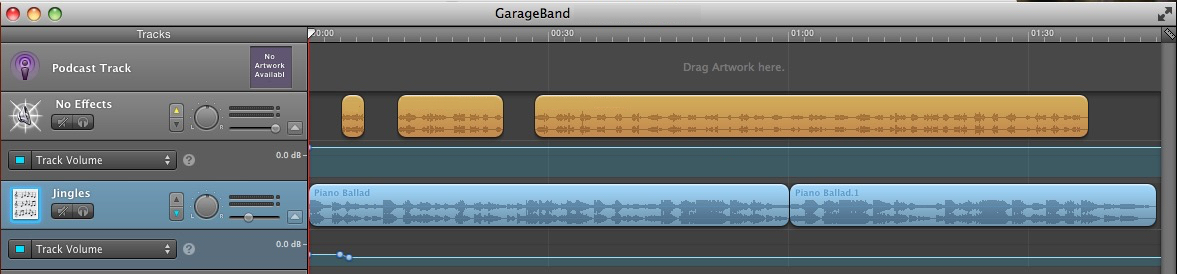

Figure 3: Screenshot of edited GarageBand file for “I Knew It Was You.”

The file in Figure 3 shows typical edits. The top sound file, in orange, is the patient’s voice; the bottom sound file, in blue, is the music loop. The music starts off with a few beats then drops in volume to allow the voice to clearly introduce the piece. The music comes back for another couple beats, setting the mood, before the voice returns. The second musical interlude, about 18 seconds in, frames a natural pause in the story. You can hear this finished piece (“I Knew It Was You”), as well as four others, below.

Once the piece is edited, the facilitator returns to the patient’s room and plays it back. The patient can make additional edits, although most do not. The facilitator then burns the file to a CD or transfers it to the patient’s laptop via a flash drive.

Sample Patient Audio Stories

As we mentioned earlier, most patients, including those who generously agreed to share their stories here, record only once, although they are given the opportunity to re-record all or part of their piece. That participants in our program consistently create highly expressive and compelling recordings in a spontaneous first take is a tribute, we believe, to their innate storytelling gifts.

We apologize if you encounter interruptions when playing the audio stories. We are working to resolve the problem.

Patient Story 1: “I Knew It Was You”

This piece was recorded during a long hospital stay while the patient awaited surgery. He met our facilitator twice, each time discussing possibilities for what he might say in a recording to his wife. He was still undecided during their third visit but didn’t want to wait another week. Despite his uncertainty, he never hesitated the moment he began recording: the edited piece above, with the exception of his selected music track, reproduces his original take almost exactly. When he was done, he expressed amazement at what he’d recorded (see the transcript of his post-recording interview later in this article). He gave his CD recording to his wife when she visited him in the hospital the next day.

Patient Story 2: “Love on an Easter Morning, 1948”

This story was recorded at the encouragement of the patient’s daughter and granddaughter, who were in the room the evening the facilitator visited. The patient told the story of meeting her late husband, with whom she had been married 55 years and raised 6 children. As happened with other patients, she seemed to fall into a kind of storytelling trance when the recorder was on, getting lost in the details and finding details she had lost. When she finished, her daughter said she’d never heard some of those details before. (This is an excerpt from a nearly 7-minute recording.)

Patient Story 3: “I Will Be There for You”

A small number of Story Studio referrals are for patients who know they are receiving end-of-life care. This patient told the facilitator that she didn’t need to discuss her audience or story material—she knew exactly what she wanted to say. They began recording immediately. Not long after, the patient left the hospital for hospice care.

Patient Story 4: “Tommy Goes to Phoenix”

When this patient was first asked by our facilitator whether she had a story she’d like to give to someone, she replied, “Do I have stories! I have so many stories!” As it turns out, she was the author of a series of unpublished children’s stories based on a fictional teddy bear character named Tommy. The character was based on an actual teddy bear the patient had been given by her grandfather when she was a girl. On the evening she recorded this piece, she was recovering from a fever, which prompted her to take her characters on a new adventure. This is one of the few fictional stories recorded by a patient in our program. (The audio file is an excerpt from a longer recording. Music credit: Frank Pahl.)

Patient Story 5: “The Trip Home”

On occasion, family members will join patients in recording a story. Pairings have included husbands and wives recalling trips together, engagements, and weddings; as well as parents and children, as was the case in this story. The patient wanted to tell the story of how he and his wife adopted their daughter 12 years earlier. His daughter was in the room and remained quiet until the recording was over. As her father tried to decide on an instrumental track, she waved the facilitator over to where she was seated. Because of her developmental challenges, she had trouble putting her request into words, but she made it clear she wanted the recorder turned on. When it was, she sang the song at the end of this recording, surprising everyone in the room. (This is an excerpt from a nearly 7-minute recording.)

Research Methodology

During our program’s first year, many patients told us how much they appreciated and benefited from recording their stories. In order to better understand their experience, we initiated an IRB-approved research project. Over the next two years, 55 patients agreed to participate, which included at least one and often two follow-up interviews. The interviews, which were recorded, focused on patients’ thoughts and feelings about the experience of participating in Story Studio. Additionally, a member of our research team listened to the audio stories for insights about the type of audience participants chose to make recordings for, the topics they talked about, and whether the recordings surfaced any organizing emotional themes. That review included an archive of 58 audio stories, as 3 patients recorded 2 stories.

Interview Methodology. Interviews were conducted in the patient’s room, although many second interviews were conducted by phone, as most patients by then had been discharged from the hospital. All were recorded (Olympus Digital Voice Recorder DM-620) with the patient’s permission. They were necessarily brief (typically 20 to 30 minutes) given the uncertainties and constraints of time in the hospital. They were semi-structured, with the same questions asked at Time 1 (1 to 4 days after recording) and Time 2 (about 2 weeks after recording), but with allowances made for patients to digress and for the interviewer to ask brief follow-up questions, usually for clarification. We designed our questions to explore the impact of Story Studio on patients’ thoughts and feelings about their hospital experience and about themselves, and on their mood and other aspects of well-being. We sought to elicit feedback about what was most memorable for the patient about their story and about their recording experience, what was surprising or unexpected, and how the experience might have changed their thoughts or feelings (Appendix 1). Within the list of questions, mood scales focused on specific ranges of feelings (eg, sad-happy, bored-interested) and asked for a rating on a scale of 1 to 10 of how the patient was feeling immediately before versus after creating their story and concluding the Story Studio session (Appendix 2). The average change in mood was 2-3 points in the direction of improved mood after the session. Estimating states of feeling in retrospect was of course a problem for some patients. Surveying their feelings immediately before and after their recording session would be easier for patients to recall, but it also would have changed the experience, at least from the patient’s perspective, to being primarily about research rather than about them and their story. Audio recordings of the interviews were later transcribed for convenience to help the team identify passages for later analysis or quotation.

Evaluating Patients’ Responses. Evaluation of the audio interviews proceeded in steps.

- First, the responses were rated by two reviewers for the patients’ global response to the experience of Story Studio – positive, negative, or neutral. Both reviewers found that most subjects felt positively about Story Studio (with none negative and only 5 seeming neutral).

- Next, to better understand the range of positive experiences, two additional reviewers rated the interviews on a 6-point scale of 0=neutral and 1 to 5 increasing degrees of positivity, from merely “ok” to enthusiastic. The reviewers were trained to pay attention to all indicators of a patient’s enthusiasm about the experience, including tone of voice and sense of conviction as well as vocabulary and phrasing. Each rater performed her rating independently and did not compare it with any others. Consensus was then built around criteria for the various ratings, with percent concordance (agreement) conveyed to the raters after each block of 10 interviews was rated. Concordance was defined as ratings within one scale point of each other. Since concordance per block was at 70% or above, we did not hold remedial training sessions.

Research Findings

We’ll first review participant demographics and general findings about the content of their stories, and then return to findings from the interviews.

Demographics. The patients in our study gave written permission to be interviewed about their Story Studio experience after they had finished their audio recording. Of our participants, 64% were female; 76% were Caucasian, 22% African-American, and 2% Hispanic. Just over half of our participants (51%) were early- to late-middle age (30-59); the next largest age group (31%) included participants aged more than 60 years. The smallest participant age group (18%) comprised people younger than 30 years. Diagnoses were wide-ranging and included cancers, organ transplants, cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, neurological and neuromuscular disorders, and autoimmune diseases, among others.

Patient Story Findings: Audience, Topics, and Themes. Most recordings were created for family members (76%), notably children and spouses. Other frequent audiences were “community” (19%), including church congregations and social support groups, and friends (10%). (A few included more than one of these categories.)

In looking at where, in time, patients focused their stories, we found most spoke about the past and the present (98%), and just over one third included a future orientation (36%). One story, recorded by a young father, was exclusively about the future: his intent was for his audio story to be played when his son, then an infant, turned 18; the patient spoke directly to his imagined future son throughout his recording.

As we mentioned earlier, patient stories were not principally about their medical conditions. In fact, less than one third of all recordings (28%) focused on an individual’s disease, illness, or injury. Instead, patients told stories about personal relationships (43%), and typically focused on the emotional themes of love and gratitude (79%), followed in frequency by loss, frustration, regret, or fear/uncertainty (26%).

Interview Findings – results and inter-rater agreement. As mentioned above, two reviewers rated the interviews on a scale of 0-5 with 5 being the most positive response to having participated in Story Studio. The overall findings, based on the review, were as follows:

- 81% of interviews were rated within 1 point of each other for Time 1.

- 87% were rated within 1 point of each other for Time 2.

- 38% of interviews were rated exactly the same for Time 1.

- 42% were rated exactly the same for Time 2.

- On the scale of 0 to 5, in which 5 was the most positive, average ratings for each reviewer were 3.0 and 3.6 for Time 1 interviews, and 3.5 and 3.9 respectively for Time 2 interviews, suggesting probable reviewer bias.

- The Pearson product moment correlation between the 2 reviewers’ ratings was 0.783, which shows high agreement in how the two raters ranked participants in relation to each other.

Patient Insights About the Bedside Recording Experience: Primary Benefits

Thematic analysis of follow-up interviews with our patient-participants took an approach grounded in the patients’ own meanings. However, the wording of the interview questions and reading of the transcripts were inevitably conditioned by our prior experience—especially by our work with patients and by our own creative work. What we had learned led to our interest in mounting this project; especially compelling were connections between creative storytelling and sense of self.

Interview questions (Appendix 1) were contributed, discussed, and refined by the authors. Audio files of the interviews were professionally transcribed and then read by a member of the research team, Robin Goldberg. Goldberg later wrote, “I began seeing similar themes appearing across multiple patient experiences [interviews]. Certain phrases began leaping off the page as particularly prominent.” These she summarized as the following themes:

- Ease of experience. Effortless collaboration with Ami; organic and authentic expression.

- Surprised by ability to create a gift. Patients were often surprised by how well their voice/story sounds and that they could provide something for someone else (often family, friend, or caregiver).

- Deep/core impact. Unexpected emotional release; opportunity to speak from the heart (patients can “be themselves”).

- Expanded perspective. Greater insight into their illness or life experiences; gratitude (appreciation of “the small things”).

- Enhanced hospital experience. More energy, less depression; view of the arts as a different type of hospital service (refreshing and positive offering).

- Inspiration for future storytelling. Among people of all creativity levels (both self-described writers/artists and non-artists); sometimes storytelling just for themselves, but mostly to provide gifts to others.

Evans then reviewed the transcripts and Goldberg’s summary themes, and, in conversations with Goldberg and Walsh, compressed into 3 categories the responses that seemed most essential and appeared most frequently. The most compelling and frequently expressed meanings shared across patients related to personal empowerment, connection to others, and a deeper life perspective.

Personal Empowerment. Of 45 Time 1 interviews in which at least 1 of these 3 categories of meaning were expressed, 35 patients expressed pleasure–from appreciation to surprise–at their ability to create such an effective or beautiful recording. For some this centered on their ability to put their feelings into words or that such strong feelings were elicited at all, and was often viewed as a personal accomplishment. Several patients wanted to continue telling stories for the benefit of others. For most patients, being made comfortable by the facilitator was credited with bringing out their best; in addition, her facility with the technology was recognized as essential to a beautiful, professional-sounding product. Here are three notable interview excerpts, the first from the patient who recorded “I Knew It Was You.”

“I remember not having my thoughts together until we started recording, and then it just came out. Like I say I know my thoughts, but I didn’t know I could put them together, back-to-back like that. Made me get more comfortable in my own skin and just relax, re-program myself and take each day as it comes.”

“That I could bring it out of me without any hesitation—that’s the main thing that surprised me. I thought I’d be able to—I mean, I thought I would break down and cry and weep or moan, and I didn’t do that because I had something I wanted to say…. (I saw) that I am a strong woman.”

“[The experience] gave me confirmation about the side that I knew was there. It gave me a little bit more confidence with the side that I knew was kind of buried deep inside.”

Connection to Others. Thirty-two of the 45 patients recognized that Story Studio provided an occasion to express to others thoughts or feelings they may never have expressed before but may have had on their minds, often for a long time. Those thoughts and feelings may have been in the past, present, or even the imagined future. Sometimes it was appreciated as a legacy for their children or grandchildren, often expressing how much those loved ones meant to them.

“As I was talking to my daughters through this recording I was sharing with them things that I saw in them, and that in a sense made me proud as a father to be able to see these certain attributes in my kids. And granted, they’re 13 and 7, so they got a long ways to go to finish growing up and learning life lessons and whatnot. But to be able to have something–and I guess this is the origin of why I wanted to do it–for them to be able to have something that they can listen to over and over and over, and like I said be able to have something to pass on to their kids. And through this I hope that it will shape and mold them as parents as they get older and they have kids of their own, that they would kind of follow suit in a sense with what I have already done with them.”

Other patients used their recordings as an opportunity to be better known to others – to loved ones, to hospital staff with whom they became close, or even directed to a donor family, as one husband did as an audio thank-you letter after his wife received a heart transplant.

“In my car I have a 50-minute drive. I must have listened to both of them 6 or 7 times and it’s what it did for me to be able to not only release my feelings and how I felt and how it’s changed me and my wife and just being able to thank the people, everyone involved and how we feel about the donor and the family. I just–we just–I really think it’s really a benefit. I’ve been thinking of ways we can use these CDs. It’s like instead of writing a letter or sending a card to people, that’s our letter to everyone that was involved to just get in a group and listen to it and see how we feel about everything that this hospital has done. It’s right there on that CD now. I just think it’s really beneficial; I mean, for us, it was.”

A Deeper Life Perspective. Sixteen of the 45 patients who had expressed at least 1 of the 3 most prominent categories of meaning (personal empowerment, connection to others, and a deeper life perspective) suggested that the Story Studio experience reminded them of or reinforced important truths about life or about themselves that were emotionally relieving. Occasionally these were new realizations, but typically they were truths that one knows but can tend to forget, especially when distracted by stress or otherwise forced into a narrow view of what’s important.

“It just really touched me that they go out of their way to do something for me, to help me, because especially being here alone for weeks on end. I call people, but it ain’t the same, you know? So that they care and there is such a program that I can relate to. It’s that feeling of they care more than just for my body but for my emotional state, too. I’ve had feelings of fear and all that. It helped relieve that, dying and stuff, [inaudible]. And they helped relieve that. And I’m a Christian so it really helped my spirit, uplifted my spirit, and gave me peace.”

In some instances the story served as a partial life review that helped clarify what may be important in the future.

“It basically put everything in perspective and kind of summarized the whole experience and made me come up with some words of inspiration for my children and kind of mapped out the next 5, 10 years and how we’re going to handle ourselves as a family.”

Listening to Patient Stories: Primary Benefits

Telling one’s story is, for anyone, “intrinsically therapeutic or palliative.”16 The listening experience, we believe, is equally beneficial for patients. Although we did not focus on collecting explicit details from patients about how they felt listening to their recorded stories (either for the first time or in the presence of their intended listeners), the general feedback we gathered was positive. The listening experience was also profoundly meaningful to the audiences for whom the recordings were made. We gained some insights from patients during our follow-up interviews about how listeners responded to their recordings, but we rarely heard directly from those listeners due to patient privacy issues. A rare correspondence with a family member came during the course of gaining patient permission to publish an audio recording in this journal. In an email, the patient’s granddaughter wrote:

“We miss her every single day, but these recordings are a blessing to us. We are able to hear her voice and listen to these stories and cherish every minute we had with her. We still wish we would have had longer with her, but these stories truly are a gift.”

After receiving patient permission to share their recordings for educational purposes, we discovered benefits to yet another significant group of listeners: clinicians and students. A small selection of patient audio stories, some of those published here, contributed to the training of physicians and rehabilitation psychologists and to the education of undergraduate students interested in a variety of careers in healthcare and applications of the arts and humanities. In teaching undergraduates, for example, for several years we have presented Story Studio in The University of Michigan’s Residential College undergraduate courses “Art, Mind and Medicine” and “Topics in the Psychology of Creativity.” And for 2 consecutive years we have been part of the Medical School’s curriculum as a 6-hour elective for second-year students. The course was titled “The Sound of Patients’ Stories: Creating Narratives at the Bedside.” Being afforded 3 2-hour sessions gave us time to provide an experience of listening to recordings of patient voices, as well as an opportunity for students to record each other telling their own personal stories. Students were unanimously positive in their assessment of the value of these experiences. (The means of numeric responses to questions about the Medical School course were consistently at 4.5 or above, on a scale of 1 to 5 in which 5 was most favorable, and 3.0 when the scale was 1 to 3 with 3 the most favorable.) The following are samples from their narrative evaluations:

“This was an absolutely amazing experience. Hearing the other students’ stories and the stories you have recorded in the hospital leaves me fulfilled in a way that I haven’t felt since starting medical school.”

“I think in 6 months, 6 years, 6 decades, I will still have a stronger appreciation for stories because of this class.”

“I know that I had an appreciation for narrative themes in medicine, but seeing the research in this field and hearing the impact it has on patients has elevated this art in my eyes.”

“Telling a story myself was well outside my comfort zone, which made it much more beneficial. The thing I will remember most is that these patients have stories to be told, and just need a medium/listener.”

We have just begun to explore what it means for individuals, from clinical hospital staff and medical students to undergraduates, to listen in small gatherings to deeply expressive and personal audio stories. Our observations and own listening experiences have raised compelling questions, especially in what way a community in-person listening experience is different from a solitary online one. From our small sample size of about a dozen gatherings, each averaging 6 to 20 people, we have seen that playing just 1 or 2 recordings consistently opens up a space for listeners to share their own personal stories about human resilience and vulnerability in the face of illness or loss.

Summary and Conclusion

The primary aim of this article is to describe in some detail our rationale and procedure for engaging hospitalized patients in expressive audio storytelling at the bedside, especially for our audience of practitioners in other institutions who are interested in adapting Story Studio to their setting (Note 5). As described previously, 3 categories of meaning, as expressed by the patients, emerged as the most salient and over-arching: personal empowerment, connection to others, and deeper life perspective.

Contributing to “personal empowerment.” Although our knowledge of the audience was important to the success of Story Studio, the element of free choice throughout the experience for patients was just as important. It contributed to the sense of personal empowerment that some patients said was a primary benefit. Free choice was conveyed to patients explicitly and implicitly, throughout the collaborative process, as well as by reminders that the experience was about them as persons–not as research subjects or even as hospital patients known chiefly by their diagnoses and symptoms. This attitude guided our entire approach–from the initial patient contact, to how we developed and maintained rapport, to working with the story material, offering music, and finally to saving the audio file as the patient’s property. All these services were provided at no charge to the patients. Only after the conclusion of the recording session were patients presented with the option of consenting to release their stories for educational purposes and to be interviewed for our research project. Acknowledging the patients’ sense of self and control was another way in which Story Studio took them beyond the hospital and its routines. In addition, many patients expressed a sense of “empowerment” explicitly – increased confidence, surprise at having produced such a beautiful product, gratitude for the facilitator’s collaboration, intention to continue to tell or to write stories.

Discovering a “connection to others.” The category “connection to others” is unsurprising, flowing directly from the writer’s opening question: “Is there someone you would like to give a story to?” That cue was a key discovery at the outset of this project—the power of telling a story not just to a sympathetic stranger, but for someone who matters.

From the standpoint of some forms of research, this can be seen as a limitation—a biasing of meaning to the patient in the direction of the audience. However, the first purpose of Story Studio was as a service, not as research. While acknowledging potential bias as we study the outcome, we also note the centrality of audience in making the experience of Story Studio what it is for patients: a bridge beyond the confines of the hospital to their personal life of loved ones and friends.

Deriving a “deepening of perspective.” The third category of meaning—a “deepening of perspective”—seemed to derive from telling one’s story. The experience prompted a shift in outlook—an expanded sense of optimism in the present, or a better ability to imagine longer-term adjustments in how to live. Once again, these meanings can serve to transport patients beyond their hospital experience as a reminder of who they are or aspire to be.

Looking Ahead

As the research phase of Story Studio draws to a close, our intention is to continue the service as a Michigan Medicine Gifts of Art bedside program, to train other facilitators, expand the service, and to continue offering educational presentations and listening events.

Appendix 1: Interview Questions

Appendix 2: Mood Scale

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge Gifts of Art staff members Elaine Reed, bedside artist; Gregory Maxwell and Wendy Azrak, bedside musicians; and Michigan Medicine nursing staff and clerks, especially on UH6A and UH8D, for their commitment to referring patients who might (and often did) benefit from Story Studio. Thank you to Julia Gaynor and Rachel Sullivan for assistance reviewing the interview audio recordings and for rating each interview for how the participant felt about the Story Studio experience. And thank you to writer Kevin McIlvoy for sharing his reflections on the human voice.

Thank you to The University of Michigan Office of the Vice-President for Research (now the Office of Research), the University of Michigan Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, and the University of Michigan Residential College, all of which provided initial funding and ongoing support for the Story Studio program and research. Thanks also to Michael Clark and Yumeng Li of the University of Michigan Consulting for Statistics, Computing and Analytics Research, for their technical and interpretative assistance. Special thanks to Candace Meyers and Carrie McClintock of Gifts of Art and Julie De Filippo of PM&R for their administrative support. We are also grateful to our colleagues and students who attended our presentations, sharing their thoughts on the Gifts of Art Story Studio listening experience.

Finally, thank you to the patients who participated in our study, took the time to give us feedback about our program, and generously gave us permission to share their audio stories with the readers of this journal.

Footnotes

- More recent studies carry the evaluation of expressive writing further by comparing it to “positive writing,” and concluding that the latter also confers benefits under some conditions.9,10 Others (including randomized controlled trials) show that the effectiveness of expressive writing can depend on factors in addition to, and perhaps interacting with, patient population, and type of health benefit; for example, within a population, variables studied include: coping style;11 personality type;12 timing of the intervention and of the assessment of outcome;13 and culture of the population.14

- Evans: In my first years on the PM&R inpatient service, during the mid-‘80s to ‘90s, patients were typically granted a day pass home on a weekend as part of their rehabilitation—their “community re-entry.” What struck me was how often that visit home improved their mood and seemed to make the remaining hospital days easier to take. More than a trial in the real world with their new level of functioning, or a break from hospital routine, I learned from my patients the importance of simply a few hours back in their life, with its own order, its unfinished projects, its privacy and familiarity. “I got to see my stuff!” captured it for me. I thought “we should study this,” to document how this brief contact with the outside brought patients back to themselves. As “leaves on pass” became rarer and now all but extinct, the focus had to shift to what could be done in the hospital to help patients remind themselves of who they are. The arts can do that. Writing and storytelling can do that.

- When we began our program, we offered patients music tracks from the sample library available in GarageBand. More recently, we have begun building a small library of our own by purchasing royalty-free music from sites such as Pond5 and AudioJungle. Michigan-based composer and musician Frank Pahl has also given us permission to use a selection of his songs for patient recordings. We are exploring the creation of an original music library for our program by working with our hospital bedside musicians, through partnerships with local musicians, like Pahl, as well as with students at the University of Michigan School of Music, Theatre & Dance.

- Audio editing, mixing and mastering is an art form. While our facilitator has a grasp of basic skills, she is not a professional sound engineer. She is grateful to sound artist and radio producer Stephanie Rowden, associate professor at the University of Michigan Stamps School of Art & Design, for her guidance on selecting recording equipment, insights about the art of close listening, and her blog (Sound and Story Salon), which offers excellent audio resources, including NPR’s Roby Byers’ The Ear Training Guide for Audio Producers, and a piece by Atlantic Public Media founder, executive editor, and executive producer Jay Allison, titled The Basics and published on Transom.

- We are especially grateful for the interest and feedback we received following our presentations at the Global Alliance for the Arts and Health, the Association for the Arts at Research Universities, and the Arts and Health Humanities conferences.

- Patient audio stories referenced in this article are available only online. For more information about this program, please contact Jeff Evans as jeevans [at] umich [dot] edu.

References

- Haque OS, Waytz A. Dehumanization in medicine: causes, solutions, and functions. Perspectives Psychol Sci. 2012;7:176-186.

- Merbitz NH, Westie K, Dammeyer JA, Butt L, Schneider J. After critical care: challenges in the transition to inpatient rehabilitation. Rehabil Psychol. 2016;61(2):186-200. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/rep0000072

- State of the Field Committee (2009). State of the field report: Arts in healthcare 2009. [http://www.arts.ufl.edu/cam/documents/stateOfTheField.pdf.

- Hanna G, Rollins J, Lewis L. Arts in medicine literature review. Paper presented at: Grantmakers in the Arts Funder Forum; February 24, 2017, Orlando, FL.

- Hardy P. An Investigation Into the Application of the Patient Voices Digital Stories in Healthcare Education: Quality of Learning, Policy Impact and Practice-Based Value [MSc thesis]. Belfast, Northern Ireland: University of Ulster; 2007. http://www.pilgrim.myzen.co.uk/papers/phardymsc.pdf

- Pennebaker JW, Beall SK. Confronting a traumatic event: toward an understanding of inhibition and disease. J Abnormal Psychol. 1986;95(3):274-281.

- Petrie KJ, Fontanilla I, Thomas MG, Booth RJ, Pennebaker JW. Effect of written emotional expression on immune function in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection: a randomized trial. Psychosom Med. 2004;66(2):272–275. [PubMed]

- Graham JE, Lobel M, Glass P, Lokshina I. Effects of written anger expression in chronic pain patients: making meaning from pain. J Behav Med. 2008;31(3):201–212. [PubMed]

- Baikie KA, Wilhelm K. Emotional and physical health benefits of expressive writing. Adv Psych Treatment. 2005;11(5):338-346.

- Baikie KA, Geerligs L, Wilhelm K. Expressive writing and positive writing for participants with mood disorders: an online randomized controlled trial. J Affective Dis. 2012;136(3):310-319.

- Junghaenel DU, Schwartz JE, Broderick JE. Differential efficacy of written emotional disclosure for subgroups of fibromyalgia patients. Br J Health Psychol. 2008;13(1):57–60. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Sohl SJ, Dietrich MS, Wallston KA, Ridner SH. A randomized controlled trial of expressive writing in breast cancer survivors with lymphedema. Psychol Health. 2017;32(7):826-842. doi:10.1080/08870446.2017.1307372

- Robinson H, Jarrett P, Vedhara K, Broadbent E. The effects of expressive writing before or after punch biopsy on wound healing. Brain Behav Immun. 2017;61:217-227.

- Lu Q, Wong CCY, Gallagher MW, Tou RYW, Young L, Loh A. Expressive writing among Chinese American breast cancer survivors: a randomized controlled trial. Health Psychol. 2017;36(4):370-379.

- National Endowment for the Arts. Arts in Healthcare: Best Practices, 2008.

- Greenhalgh T, Hurwitz B. Why study narrative? BMJ. 1999;318:349.

Member since 2019 | JM14274

Member since 2019 | JM14274

NO COMMENT