Table of Contents

Poet and critic Larry Eigner (1926-1996) began writing poems in his teenage years and never quit. As a result, The Collected Poems of Larry Eigner (2010) comprises four tall volumes containing a total of 3,072 poems, which is precisely as remarkable a quantity as it seems. Comparatively, Shakespeare penned 154 sonnets and Thomas H. Johnson enumerated 1,775 poems for Emily Dickinson. Eigner’s poems vary in length (lines to pages) and subject (nature and climate change to pop culture and language) in ways too numerous to list, but an abiding artistic concern worth ample consideration is to be found in their innovative typography. In this untitled three-line poem from December 26, 1979, note the way each line grows by one letter added to the second word and each line drifts further away from the origin:

It’s not

too late

for words1The language is simple, but its tones—perhaps cautious optimism? desperation? refusal? humor?—are amplified by the way it is formatted. The barely hanging-on, last-minute fulfillment of the poem’s promise achieved by “words” saving the day stages a small-scale drama that might be totally missed were it typed as a single line.

That the typewriter was an indispensable part of Eigner’s poetic and critical practices is a claim that exceeds bare materiality, as any number of twentieth-century writers composed on typewriters. In his prose piece “Rambling (In) Life another fragment another piece” Eigner explains, “From a forceps injury at birth (August 7 ’27) I have cerebral palsy, CP.”2 Eigner spoke and handwrote in ways that could be difficult to understand for the unfamiliar listener or reader. He had a particular understanding of using speech effectively as he recounted in an interview: “You know my mother said to me to communicate you must speak clear … first of all … though I soon realized that immediacy and force take priority.”3 As for how Eigner composed the majority of his work, he pressed the typewriter keys one at a time with one finger to write out his poems. However, just because he could produce readily legible texts via the typewriter far more exactly than he might have with script does not in itself fully explain his investment in developing an ingenious spatial poetics.

Certainly, typing three thousand poems on a typewriter is a Herculean effort worth admiring, but I am equally compelled by Eigner’s attention to the pleasures provided by pursuits of the mind. I’d like to suggest that this pleasure must have been a fundamental condition for Eigner’s commitment to his art. “Reading, the beach and everything else was like vacation compared to physiotherapy, which was tough, scholarship was something to look forward to,”2 writes Eigner. In an essay on writing and poetry, he further explicates the reward of effort, saying that even difficulty, as in his writing practice, need not be scorned entirely: “If a thing is hard enough, no one can do it. I enjoy doing things that are easy enough. If it gets to be work, physically tiring, still it’s enjoyable work.”2 Finally, in “Disco,” a poem that to mind cannot be called anything other than jubilant, the poet celebrates typing outright:

D i s c o

like new yr’s eve

all year through

there’s a typewriter sound

what of the day1Eventually, through poetry and literature, Eigner found a community likewise invested in exploring the complex paths linking artistic production and meaning. Charles Bernstein, remarking on Eigner’s sui generis typography comments on the relative isolation of Eigner’s artistic beginnings: “[I]t’s one of the really monumental achievements of American art in my view, what Eigner achieved that way, and actually in an entirely [familial but otherwise largely] unsocial space of the ’50s.”4 This unsocial space gave way to meaningful friendships and exchanges with many poets including the Language poets and Black Mountain poets. One such Black Mountain poet, Denise Levertov, observed in the introduction to Eigner’s book On my Eyes, “He regards spacing and punctuation rightly, as tools, and does not voluntarily obtrude them between the reader and the poem which they should be unnoticeable supporting.”5 Famously, Eigner also issued a challenge to the runaway freight train of a poetic manifesto, Black Mountain College Rector Charles Olson’s “Projective Verse.” “Projective Verse” called for a decidedly embodied poetic practice based largely on structures of speech and breath, which Olson thought the typewriter could exactly duplicate. In response, Eigner offers a poetry based first on “[t]hought voiced and/or in the mind.”2

After this snapshot, you still have 3,070 of Eigner’s poems left to enjoy. In a world where handbooks of poetic terminology line library shelves and graphic design is an overwhelmingly popular art form, we still lack an exact critical language to describe much of what these poems do spatially. Larry Eigner was a poet of singular dedication whose work contains many foci from enjoyment and pleasure to observation and reflection, and betterment and learning—all of which, in this case, end up on the page.

Poems from The Collected Poems of Larry Eigner, Volume 3, edited by Curtis Faville and Robert Grenier. Copyright © 2010 The Estate of Larry Eigner. Permissions generously granted by the Estate of Larry Eigner.

References

- Faville C, Grenier R, eds. The Collected Poems of Larry Eigner. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press; 2010.

- Friedlander B, ed. Areas Lights Heights. New York, NY: Roof Books; 1989.

- Interview with Jack Foley on WKPFA. Penn Sound Web site. http://writing.upenn.edu/pennsound/x/Eigner.php. Accessed March 23, 2017.

- Bernstein C. On Larry Eigner, ‘On My Eyes.’ Jacket 2 Web site. http://jacket2.org/article/larry-eigner-my-eyes. Published May 2,2011. Accessed March 10, 2017.

- Eigner L. On My Eyes. Highlands, NC: Jonathan Williams; 1960.

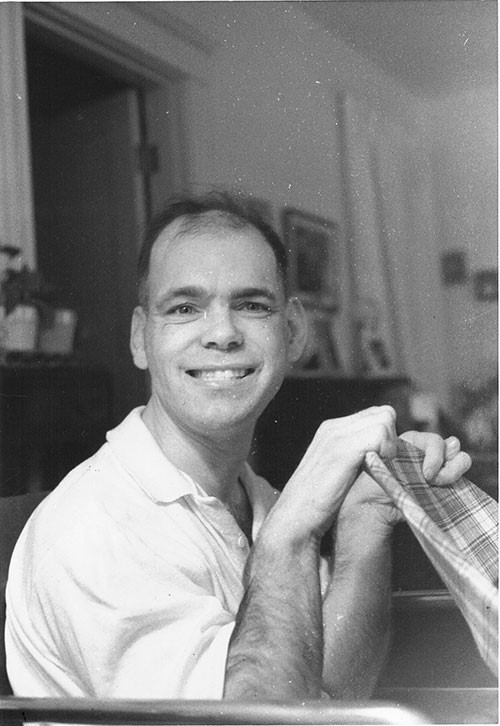

About the Author(s)

Joe Fritsch

Joe Fritsch is a poet and a PhD Student in the English Department at Emory University, where he also works as a Digital Scholarship Associate. His interests include 20th century and contemporary poetry, media studies, and performance studies. Prior to moving to Atlanta, he received a BFA in Poetry from Brooklyn College and worked at New York City’s Poets House for half a decade.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.