Remnants of Her

By Holly Huye, PhD, RD

My mother looks like a homeless person. She is wearing a stained shirt and cardigan with a hole in it, and she has greasy hair. She is not the woman who once had her hair done every six weeks, and who frequently visited the Clinique and Estee Lauder counters where she would buy moisturizers and make-up. Her clothes were tailored and classic from Talbots and Brooks Brothers. My parents had an active social life, often going out to dinner with friends or to parties and plays. Now, they go to doctor appointments.

The changes started slowly with mild cognitive impairment, mixing words up and forgetting every-day things, like what to do with the jelly at Waffle House. My mom was an excellent cook; so, when she didn’t know what to do when the recipe called for the onions to be sautéed, it was heart-breaking. The saddest part, she knew she was losing her mind and would say to me, “I’m ready to die; this is no way to live.”

She fell and fractured her hip and was in the hospital for over three weeks; she went home on Christmas Eve. I remember crying every day that month; my parents missed my graduation when I completed my doctorate, the only graduation in which I actually “walked”. Depressed, she never wanted to leave the house, still saying she wanted to die. Four years after falling, her dementia stripped her of all memories. She was an avid reader. Now, the only evidence of her passion that remains is the novels she read, which are stacked up in an unused bedroom.

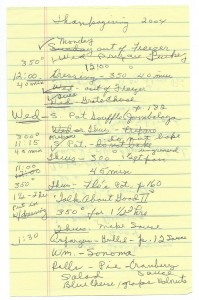

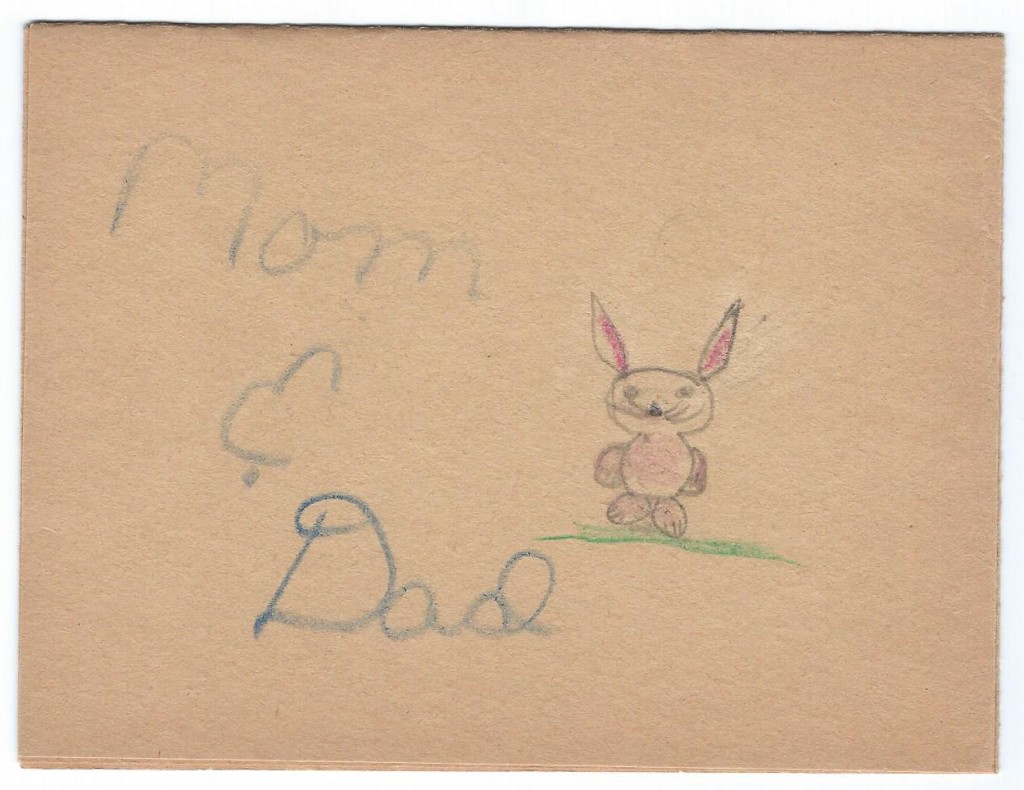

These surviving traces are the small remnants of her past life that are left. When I think about her life, so much of it revolved around cooking. Her favorite cookbooks line the kitchen shelves, so frequently used that they are held together with rubber bands. When we were little she made everything from scratch – even chocolate pudding. For us five kids, she routinely made a big breakfast of pancakes and bacon after coming back from swimming practice in the summers, and she made the best oatmeal cookies and brownies on the block. We ate dinner at 6 o’clock every night. She didn’t work outside of the home until I was in the 3rd grade; but even then, dinner was still on the table at 6pm – sharp. Every Thanksgiving and Christmas she would plan the dinner using “yellow notes.” She was so detailed that she wrote down the times she basted the turkey until it was done. She saved the notes for years, dating back to 1988. She also saved every card we ever gave her in her collection of cookbooks.

While I’ll never be as good a cook as my mother, I now have many of her cookbooks along with our cards. She kept those precious memories of us for herself. Now, I keep them to preserve her memory for me. I have adopted her practice and continue to keep special cards people give me in my collection of cookbooks. I often see in myself remnants of her – her cooking, her desire to please, and her creativity. These are the remnants of her past that I treasure most.

While I’ll never be as good a cook as my mother, I now have many of her cookbooks along with our cards. She kept those precious memories of us for herself. Now, I keep them to preserve her memory for me. I have adopted her practice and continue to keep special cards people give me in my collection of cookbooks. I often see in myself remnants of her – her cooking, her desire to please, and her creativity. These are the remnants of her past that I treasure most.

She does not know my name, but bits of lyrics from Frank Sinatra or other “rat packers” come to her occasionally, and she will burst out into song and then laugh after. Few words and phrases remain in her vocabulary, like “mama”, “my children”, “I’m going home”, and “we are falling on the floor”. My parents did not often show affection, so now, to see them sit together and hold hands while singing show tunes, is a new memory for me.

I have observed how unforgiving and cruel dementia is – it robs one of dignity and one’s identity. It is said in Mexican folklore that there are three deaths. The first is when the body ceases to function. The second is when the body is consigned to the grave. The third is that moment, sometimes in the future, when your name is spoken for the last time. In some ways, those with dementia who lose their minds, with no living memories, with no connection to the present, and no expectations for the future, die an existential death, unless we, as survivors, take the unspoken responsibility to keep those memories alive and celebrate them in the present.

I have observed how unforgiving and cruel dementia is – it robs one of dignity and one’s identity. It is said in Mexican folklore that there are three deaths. The first is when the body ceases to function. The second is when the body is consigned to the grave. The third is that moment, sometimes in the future, when your name is spoken for the last time. In some ways, those with dementia who lose their minds, with no living memories, with no connection to the present, and no expectations for the future, die an existential death, unless we, as survivors, take the unspoken responsibility to keep those memories alive and celebrate them in the present.

Member since 2019 | JM14274

Member since 2019 | JM14274

NO COMMENT