Matisse: Innovation in the Face of Physical Limitations

By Siobhan Conaty, PhD

Henri Matisse (1869-1954) trained as a lawyer, then changed course in his early twenties, choosing a path that would earn him the moniker “king of the wild beasts” and ultimately transform the history of modern art. The son of a successful grain merchant, he rejected the more suitable career to follow his passion to create art. He left the south of France in 1891 to study at two of the more traditional institutions in Paris, the Académie Julian and later the École des Beaux-Arts. But the innovative and overlapping avant-garde styles that Matisse discovered on arrival in fin-de-siècle Paris had a greater impact on his fine arts education. Matisse would have witnessed and absorbed the ground-breaking work of Claude Monet and the Impressionists along side Post-Impressionists such as Vincent Van Gogh, Paul Cezanne, and Georges Seurat.

By the turn of the twentieth century, Matisse led a new group of avant-garde artists, the Fauves, known for thick brushstrokes and brilliant colors that had been completely liberated from the customary descriptive role in art. The name “les fauves,” (wild beasts) came from the critic Louis Vauxcelle’s insult, “Donatello chez la fauves!”1 upon seeing a Renaissance sculpture by Donatello placed among paintings by Matisse and other avant-garde artists of the time.

Although this style was short-lived, Matisse’s search for pure color expression left a lasting mark on twentieth century art. Matisse summarized his aesthetic goals in a 1908 statement that would remain true of his works until the end of his life:

[pl_blockquote]It is not possible for me to copy nature in a servile way; I am forced to interpret nature and submit it to the spirit of the picture. From the relationships I have found in all the tones there must result a living harmony of colors, a harmony analogous to that of a musical composition.2[/pl_blockquote]

These ideas are evident in post-Fauve paintings such as Dance I (1909) (Fig.1), where Matisse used a favorite topic, the human figure, to continue his search for pure expressive color. He integrated simple forms and a strong rhythmic use of line that simulates the experience of visual and musical harmony. One can clearly trace these principles throughout Matisse’s oeuvre to the cut-outs he conceived and developed in the final, and most physically challenged, years of his life.

Fig. 1: Henri Matisse, Dance I, 1909, Museum of Modern Art, New York, Image Credit: © 2016 Succession H. Matisse / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

When Matisse was diagnosed with duodenal cancer at the age of 72, he was already experiencing crippling pain. He nearly died from complications of the surgery in 1940, but eventually made what was considered a remarkable recovery. However, the resulting physical damage was considerable. Matisse’s abdominal muscles were so weakened, he could only stand and sit upright for short periods each day.3 But his creativity was not diminished, so Matisse developed a series of solutions to the dilemma of making art, working around the physical limitations of his ailing body.

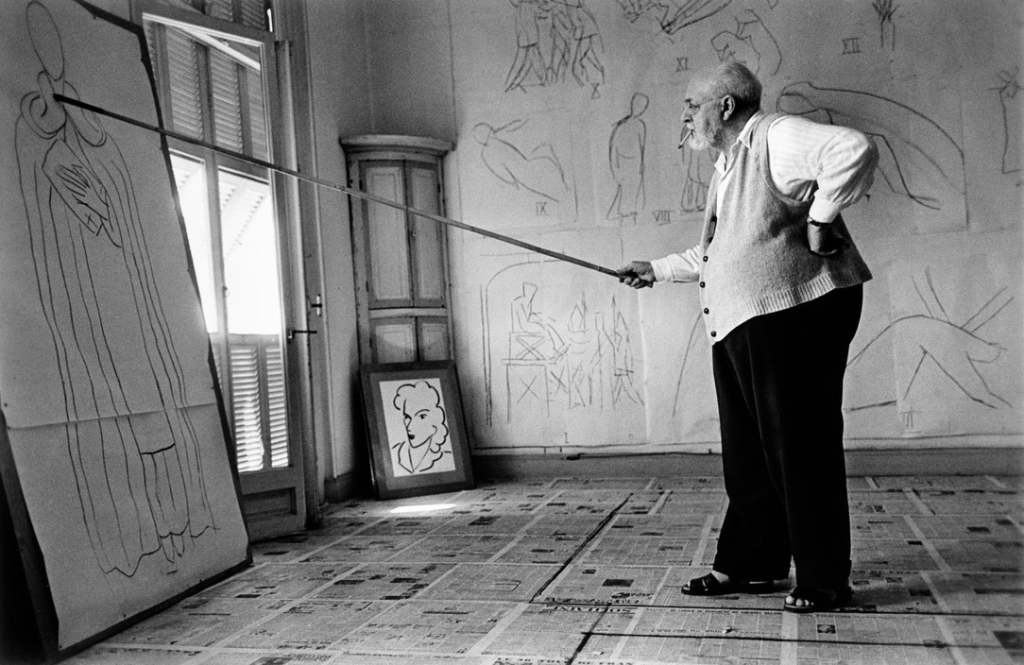

Fig. 2: Robert Cappa, Henri Matisse in his Studio, Nice, France, 1949. Image Credit: © Robert Capa © International Center of Photography/Magnum Photos

Photographer Robert Cappa captured an iconic image of Matisse using a bamboo pole with charcoal attached to the end so he could draw shapes on paper lining the wall. (Fig. 2) The art critic John Richardson visited the artist in his studio in Nice in 1951, and described this instrument as Matisse’s secret weapon, a twelve foot bamboo cane strapped to his hand, which the artist used “much as a conductor would lead an orchestra with his baton.”4 When he was no longer able to stand, Matisse worked from his bed or his wheelchair “painting with scissors,” (Fig.3) that is, cutting shapes from colored papers that he had arranged and re-arranged on his studio walls until he was satisfied with the overall composition. He surrounded himself with images of places he could no longer physically visit: gardens, the sea, memories of his journey to Tahiti.

Fig. 3: Philippe Halsman, Henri Matisse in his Studio, St. Paul de Vence, France, 1951. Image Credit: © Philippe Halsman/Magnum Photos

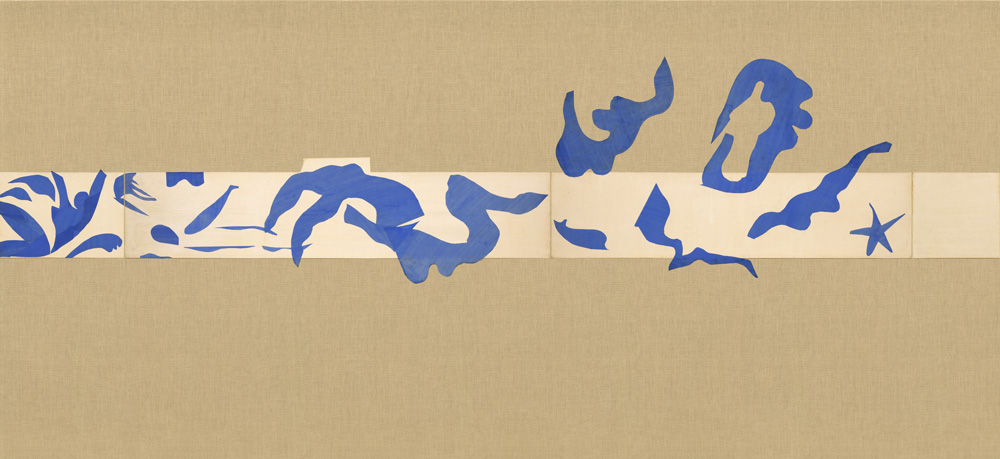

The Swimming Pool (1952) (Fig.4) was created after Matisse realized that a trip to his favorite pool in Cannes was too physically demanding. He returned home and began to craft his own pool, instructing his assistant to wrap a band of white paper along the brown burlap of his dining room walls. Using brilliant cobalt blue painted paper, Matisse cut the simplified forms of bodies swimming, floating, flipping, and diving and arranged them around the room. These dynamic, fluid shapes flow across the walls like musical notes, providing Matisse with the harmony with nature he so craved in art and life. The sheer joy of unencumbered movement is also evident in these late works. This was not a new concept for Matisse; he celebrated the beauty and harmony of the dancing figure throughout his career, but this particular series was perhaps meaningful as his own ability to move freely became less and less possible.

Fig. 4: Henri Matisse,The Swimming Pool Maquette for ceramic (realized 1999 and 2005). Nice-Cimiez, Hôtel Régina, late summer 1952. Gouache on paper, cut and pasted, on painted paper; overall 73″ x 53′ 11″ (185.4 x 1643.3 cm). Installed as nine panels in two parts on burlap-covered walls 11′ 4″ (345.4 cm) high. Frieze installed at a height of 5′ 5″ (165 cm). Mrs. Bernard F. Gimbel Fund. © Succession H. Matisse / ARS, NY.

As Jules Morgan noted in The Lancet, Matisse had the “insatiable need to keep creating and keep working, as his life, his creations were interdependent.”5 His search for pure color, joy, and harmony in art was not impeded by his disabilities; instead, he managed them as a means to accomplish some of his most triumphant works. Matisse didn’t just continue to make art until the end of his life in 1954; he worked with and around his physical limitations to develop the cut-out technique, resulting in some of the most visually stunning compositions in the history of modern art.

References

- Vauxcelles L. Le Salon d’Automne. Gil Blas. October 17, 1905. Screen 5-6. Bibliothèque Nationale de France.

- Matisse H. Notes d’un Peintre. La Grande Revue. December 25, 1908. Translated by Flam J. Matisse on Art. Los Angeles CA: University of California Press, 1995.

- Flam J. Matisse on Art. Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press; 1995: 234.

- Richardson J. Matisse’s Cutting Edge. Vanity Fair. October 2, 2014. http://www.vanityfair.com/culture/2014/10/matisse-cut-outs-moma-john-richardson. Accessed October 12, 2016.

- Morgan J. Henri Matisse: cutting into colour. Lancet. 2014; 383:1878.

Member since 2019 | JM14274

Member since 2019 | JM14274

NO COMMENT