The Diving Bell and The Butterfly: From the Eye of the Unseen

By Sarah Caston, PT, DPT, NCS

The Diving Bell and the Butterfly was written by Jean Dominique Bauby, following a catastrophic stroke resulting in Locked In Syndrome. Locked In Syndrome (LIS), also known as “pseudocoma,” is caused by a severe brainstem stroke. The resulting physical effects include complete paralysis, except for sparing of eye musculature, while also preserving full conscious awareness. This sets the background for Bauby’s memoir. The story opens with the 43 year old as he finds himself waking in a hospital bed, paralyzed except for the use of one eye and unable to verbally communicate. The novel proceeds from there, capturing his lived experience as a patient in Berk- Sur- Mer hospital in northern France, as well as the author’s reflections on the successes of his past and regretful experiences. Initially the story consists of reflections and an awakening to his realizations regarding his injury’s effects and implications. Eventually, the memoir takes a turn, as does Bauby’s thoughts with regards to his imagination, current state of mind and body. The story continues beautifully, utilizing metaphors, in which he describes the “diving bell” as his physical body, holding him captive, literally “locking him in.” Conversely, once he re-discovers his imagination as a free flowing creature that can “travel to far off lands” and traverse time, he then speaks of this as a “butterfly.”

“I decided to stop pitying myself. Other than my eye, two things aren’t paralyzed, my imagination and my memory.”

—Jean-Dominique Bauby

The detailed and beautiful language in this book almost pales in comparison to the diligence in the technique it required to transcribe it. As Bauby continues to undergo speech therapy sessions in the hospital, he begins to flex his freedom of thought with the assistance of his speech therapist. With her ingenuity, Bauby was able to learn a new “language” (alphabet rearranged in order of most frequently used letters to the least) and transcribed this book. Utilizing this alphabet to transcribe was formidable in its very nature – each word took 2 minutes to translate and transcribe, and the entire book took 10 months, with the author blinking 4 hours a day to write the book. The fact that this literary piece was written without lifting a pen, pressing a key or opening a mouth is a notion worth a moment of admirable consideration.

This book reaches to the innermost heart strings and gives them a tug: abruptly at times with sarcasm, strummed with dreamy illustrations of night time images, and picks at them with jabbing language as the author describes being “seized” and “dumped” into a wheelchair. Such phrases, written by this young man who survived a catastrophic hemorrhage, give us a glimpse from a literal “eye” into one of the most rare stroke related syndromes (LIS). His story is rich with wit, honesty, grief and hope that will have you smirking through tears and chuckling in the face of devastation.

It is enlightening to the reader as he writes of his “helplessness” in scenarios and feeling invisible throughout the book. One such experience was when the ophthalmologist began to sew his eye shut without receiving consent (which, ironically, would have been an eye blink). Bauby describes how daft the man must have been to be looking so closely at him, only to see right through him. He continues to relay his disgust and fear as the physician clearly missed the stare of reluctance in his eye as it was being closed. At other times, he was spoken for over and over- and his inner “butterfly” (representing his imagination and thoughts) shuddered in disagreement, while his “diving bell” body refused to move in cooperation. Even in the moments when well- intended individuals tried to help, he was frequently robbed of his own thought process and expression. An example was when he was spelling out “lunettes” (French for ‘glasses’) and before he could complete the phrase, someone assumed he was spelling “lune” (French word for moon) and starting discussing the moon with him.

However, the most powerful aspect of the book and the stronger underlying theme was his amazing ability to recognize the power of the mind; the understanding that the ability to self -reflect, to remember, to escape– as he describes traveling to far off lands in his mind- was a destroyer of disability in its own right.

In just a brief period of time, it appears he undergoes a transformation of sorts; a redefinition of self. He at one point describes himself as “fading away” after living in the solitude of his hospital room day after day. However, he combats this notion through recognitions of the things that make him feel “human”, allowing him a temporary escape from the diving bell. These preserved notions of his former self, something as “trivial” as wearing cashmere sweaters, as well as reminiscing over previously enjoyed activities, such as driving, and eating, bring him joy.

“Hold fast to the human inside of you, and you’ll survive.”

—Roussin

One of the most poignant parts of the book was the underlying theme of pain opening a window to clarity. In the very beginning of the book, after he describes his horrible ordeal with the wheelchair introduction, he declares that the abruptness of the situation (being seized and tossed in to the wheelchair without much, or any, explanation) was actually clarifying and “helpful.” It allowed him to more quickly realize and accept the dependent nature of his physical state, which, possibly led to recognition and embracing of his mental independence for meaning and substance.

Overall the book is impressive with its dynamic variety of literary themes, though the chapters are very brief, and somewhat choppy, moving from subject or situation in somewhat of a sudden fashion. Perhaps, from a psycho- emotional perspective, these frequent shifts of reflective thoughts may represent the experience of disability, depicting the fluctuating ebb and flow of both grief and hope.

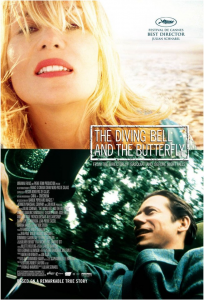

The 2007 biographical film of this story was also captivating and revealing, offering a unique perspective that even the most descriptive paragraph could not. For example, in the opening scene, Bauby is peering through one eye, with wavering vision- images that are clouded, as are the voices that he is trying to interpret. This striking perspective offers a potential glimpse into a reality that many of our patients experience as they arouse from deep sedation after surgery, or, a catastrophic event such as a stroke.

The actor portraying Jean Do Bauby (Mathieu Amalric) was exceptional in his ability to make such strong statements without physically uttering a word. This fierce portrayal leads one to realize the striking impression of this dominant, one-sided perspective of the movie. Certainly many movies depict actors playing inner monologues, but rarely does one witness the frustration and futility of an inner monologue left completely unexpressed. That is, until Bauby’s speech therapist Henriette (Marie-Josée Croze) and transcriber, Claude Mendibil (played by Anne Consigny), offered him an escape from his “diving bell” by offering a new language, transforming his inner monologue into shared thoughts, hopes and desires.

The movie differs somewhat from the book in the depiction of Bauby’s grief and how he copes with his life post stroke. The movie presents, through frustrated verbalizations of the actor’s voice, dimly lit hallways and drowsy, dream- like scenes, and a deeper depression than I had perceived him experiencing from the book. Generally, however, the film complements the book, offering beautiful flashback scenes depicting his relationships, a gorgeous indulgent dinner as he longs for the taste of food, and precious time spent with his children.

Tool for Teaching

Bauby’s story is a compelling personal journey and both formats of book and film can serve as powerful educational tools for students. Case studies and textbooks are essential to teach the science/physiology behind injury but lack the ability to provide a meaningful resource for students to begin to comprehend their patient’s experiences. Too often, healthcare professionals focus on identifying what is “wrong” (pain, impairment, functional limitations), then develop a plan to “fix” those things. Less often do we seek what truly brings our patients hope and freedom from whatever physical limitations they may experience. Ironically, this paternalistic view, or “savior complex,” has the potential to build a wall between therapist and patient. Jean Dominique Bauby’s complex story eloquently reveals the many complex layers of emotions and desires associated with a catastrophic injury. More importantly, it highlights the ABILITY of someone who was called a “vegetable” by those close to him and shows the imagination and ingenuity of a brain physically damaged but intellectually stimulated. If we, as healthcare professionals, can allow ourselves to look beyond the notion of “fixing” an individual, and promote self-efficacy within our patients, we might just discover a mutually freeing experience.

References and Awards

Book

Bauby JD. The Diving Bell and the Butterfly (Jeremy Leggatt, Trans). New York, NY: Knopf, 1977

Film

Schnabel J. The Diving Bell and the Butterfly (Le Scaphandre et le Papillon, Original Title). [DVD] France/US: Pathe Renn Productions; 2008

Awards

Film version won numerous international awards in 2008, including 4 Oscar nominations (Best Achievement in Directing, Best Writing/Adapted Screenplay, Best Achievement in Cinematography, Best Achievement in Film Editing), 3 Golden Globe nominations (Best Screenplay, Best Director – won, Best Foreign Language Film – won), British Academy of Film and Television Arts (Best Screenplay), American Film Institute Awards (Movie of the Year), Cesar Awards, France (Best Actor and Best Editing) and Cannes Film Festival 2007 (Best Director).

Member since 2019 | JM14274

Member since 2019 | JM14274

NO COMMENT