Frida Kahlo’s Body: Confronting Trauma in Art

By Siobhan M. Conaty, PhD

Frida Kahlo remains one of the few artists whose recognition reaches beyond the professional art world and into the realm of popular culture. Academic books and solo exhibitions have been plentiful over the past few decades, but there are also children’s books, jewelry and clothing, dolls and puppets, movies, and other memorabilia – all for an entire sub-culture of dedicated Kahlo fans. A closer look at how Kahlo represented the trauma in her art and life provides some clues to the fascination with her work.

Born in 1907 in Mexico City to a German father and Mexican mother, Kahlo was fiercely proud of her mother’s culture and often felt conflicted with the European side of her ancestry. She ultimately changed the spelling of her name from the German “Freida” to the Mexican “Frida” and accentuated (some would say exaggerated) her Mesoamerican heritage with her clothing and hairstyles.

At the age of six she contracted what most believe to be polio,1 and spent almost a year in convalescence, resulting in a weakened and withered right leg that was amputated at the end of her life. Despite her childhood health issues, Kahlo was a bright young woman who was accepted into Mexico City’s prestigious National College Preparatory School in 1922, where she was one of only thirty-five women in a school of two thousand students.

Kahlo was involved in a horrific streetcar accident at the age of eighteen where her pelvis was impaled by a metal rod, her was spine shattered, and the rest of her body endured multiple additional fractures.2 Based on the state of hospitals and medical responses to trauma at the time, Dr. Robert Ostrum, an orthopedic trauma surgeon, has noted that “to survive this in 1925, was close to a miracle, even at age 18 … if she had been 50 or 60, it would have been a death sentence.”3 She spent the rest of her life trying to recover from this trauma, undergoing over thirty operations to treat the painful injuries to her spine, legs, torso and pelvis.

Confined to bed in a full body cast for months, Kahlo took up painting using a contraption fitted to her bed so she could work from a supine position. (Fig.1) Prior to the accident, Kahlo had planned to study medicine and become a doctor, but after the accident she found a new direction, she wanted to become an artist. She never lost interest in anatomy, biology, or her fascination with the body – she simply shifted her attention to these subjects in her art. She often painted her body casts and surgical corsets, turning the sterile and stark medical equipment that dominated her life into striking works of art. Part of Kahlo’s appeal is that she managed to find ways to work around her fractured and broken body to create powerful works of art that still resonate with viewers today.

In the years following her accident, Frida became dedicated to both art and revolutionary politics. Through these interests, Frida met and married Mexico’s most famous muralist, Diego Rivera, when she was twenty-two years old. Frida’s parents, who were dismayed with this match, described the union as “a marriage between an elephant and a dove.”4 Rivera was indeed a large man, twenty years her senior, a communist, and a controversial figure. Despite the many trials and tribulations of their personal relationship, Rivera supported Kahlo’s work unconditionally. He introduced her to Andre Breton, a founding figure of Surrealism – an art movement whose members embraced Frida’s art whole-heartedly. The Surrealists celebrated Freud’s writings on dreams and the unconscious mind, encouraging artists to use the irrational as subject in their art. Breton quickly claimed Kahlo as one of his own, describing her works as “pure surreality, despite the fact that it had been conceived without any prior knowledge whatsoever of the ideas motivating the activities of my friends and myself.”5 Although Kahlo benefitted from her association with the Surrealists, she made a clear distinction in a 1953 interview with Time Magazine, asserting, “(t)hey thought I was a Surrealist, but I wasn’t. I never painted dreams. I painted my own reality.”6 And Frida’s “reality” was undeniably on par with some of the most imaginative works by her fellow Surrealists.

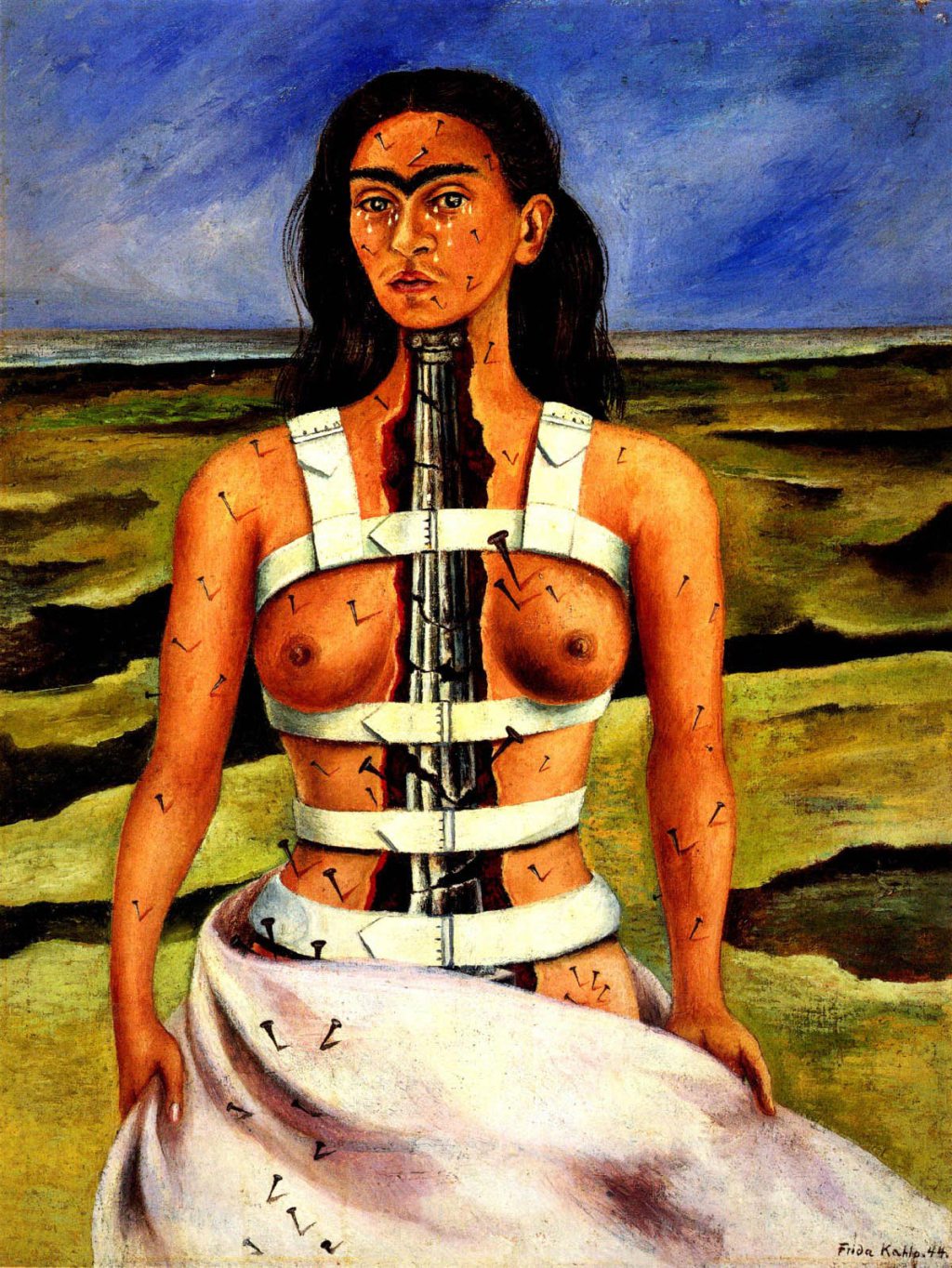

In the last decade of her life, Kahlo’s health had deteriorated to the point where she could barely sit or stand without the support of medical casts and corsets. Her self-portrait, Broken Column (1944) (Fig.2), demonstrates both the physical and psychological pain she endured. Her spinal column was replaced with a cracked and damaged Ionic column, the most slender and delicate of the Greek order of columns. Although torn apart at the center, her body stands upright, held together with a surgical brace. Kahlo stands strong and stoic despite the nails that pierce her flesh. She positions herself in a barren and fractured landscape, a symbol of her own loss and infertility that can be seen in many of her works. While tiny points of pain radiate across her shattered body, Kahlo’s gaze remains strong. She makes direct eye-contact with the viewer, a conscious choice, putting herself in the position of active subject, rather than a passive object to be “looked at” – the standard pose for women in the history of art.7 Kahlo maintains a position of power here, using her body and her gaze to prevent the portrait from entering into the realm of pity. The tears she sheds provide evidence of the effects of the physical pain, but Kahlo’s paintings have the unique ability to project her strength rather than emphasize weakness or disability.

Frida Kahlo, Broken Column (La Columna Rota), 1944, oil on masonite. Collection of Dolores Olmedo Mexico City, Mexico. Credit: © 2015 Banco de México Diego Rivera Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, Mexico, D.F. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Reproduction, including downloading of Frida Kahlo works is prohibited by copyright laws and international conventions without the express written permission of Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

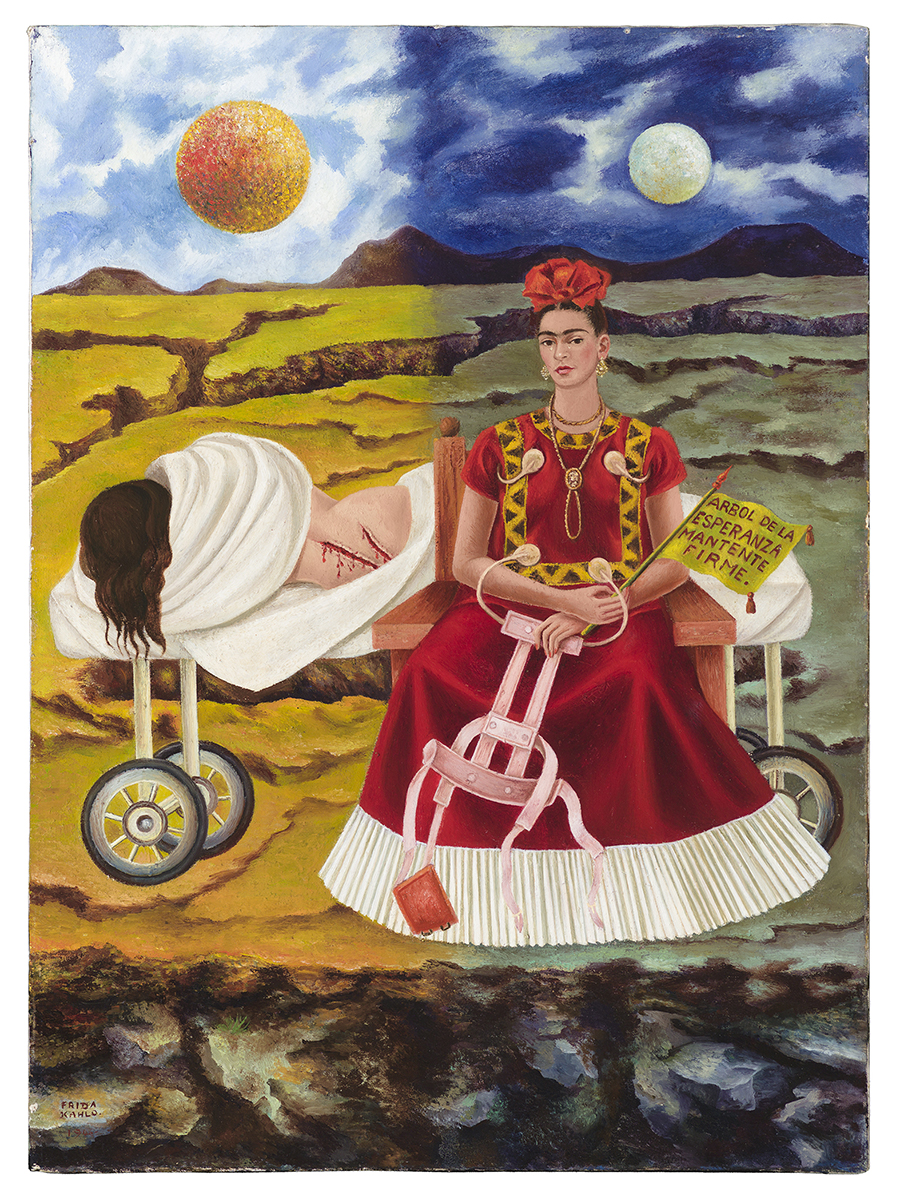

Frida painted Tree of Hope (Fig. 3) in 1946, the same year underwent an operation in which a metal rod was inserted to strengthen her spine and four of her vertebrae were fused together. She spent most of the following year wearing a steel corset and taking morphine to help manage the severe pain.8 She depicts two Fridas, one sick and one healthy, sharing the same hospital gurney in a cracked and desolate landscape. The sick Frida, nude and reclining, bears the scars of her recent surgery whereas the healthy Frida sits regally in her Tehuana dress casually holding a steel corset in one hand and a flag in the other that reads “Tree of hope stay strong.” Kahlo presents the dualities of her life; light and darkness, the sun and the moon, the broken body and the vibrant body, living and dying. Kahlo asserts both sides of her experiences – she refused to hide her sick, fragile, and bleeding body, putting it alongside her strong, sensual, and captivating body.

Frida Kahlo, Tree of Hope, Remain Strong, 1946, oil on masonite. Collection of Daniel Filipacchi Paris, France. Credit: © 2015 Banco de México Diego Rivera Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, Mexico, D.F. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Reproduction, including downloading of Frida Kahlo works is prohibited by copyright laws and international conventions without the express written permission of Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

In 1953, one year before her death, Kahlo was given her first solo exhibition in Mexico. Her doctors told her she was too sick to attend, but in true form, Kahlo arrived by ambulance, was brought in on a stretcher and lay in her bed placed in middle of the gallery and received her guests. When she died at the age of forty-seven in 1954, Kahlo’s open casket was placed in the lobby of the Palace of Fine Arts, the most important cultural institution in Mexico. More than 600 people came to mourn and pay their final respects. The casket was adorned with the communist symbol of a hammer and sickle, causing some controversy among leaders of the city – this certainly would have pleased Frida.9 Even in her death, Kahlo used her body to demand our attention and respect, not our pity.

References

1. Kahlo’s early medical history is primarily based on her own recollections. It wasn’t until 1946 that her OBGYN, Dr. Henriette Begun, compiled a concise overview of her medical history.

2. Lomas, D and Howell, R. Medical imagery in the art of Frida Kahlo.” BMJ. 1989; 299(6715): 1584-1587.

3. McCullough, M. Kahlo’s suffering, medical care didn’t help. The Philadelphia Inquirer. March 17, 2009.

4. For biographical details, see Herrera, H. Frida: A biography of Frida Kahlo. New York, NY: Harper Perennial; 2002.

5. Andre Breton’s introduction to Frida Kahlo’s 1938 exhibit at Julien Levy’s gallery in New York. Quoted in Chadwick, W. Women artists in the Surrealist Movement. New York, NY: Thames & Hudson; 1985: 90.

6. Márquez, F. Mexican autobiography. Time Magazine. April 27, 1953: 90.

7. See Laura Mulvey’s important essay on gender and looking, Visual pleasure and narrative cinema. Screen. Autumn 1975; 16(3): 6-18.

8. Lindauer, MA. Devouring Frida: The art history and popular celebrity of Frida Kahlo. Middleton, CT: Wesleyan University Press; 1999: 76.

9. Zamora, M. Frida Kahlo: Brush of anguish. San Francisco, CA: Chronicle Books; 1993: 133.

Member since 2019 | JM14274

Member since 2019 | JM14274

NO COMMENT