The Anatomy Studies of Thomas Eakins

By Angela Fritz, MA

Since ancient times, art and science have shared common boundaries; many famous artists have used scientific experimentation to understand their surroundings more fully. Thomas Eakins (1844-1916) was one of these artists, who considered his interest in anatomy, perspective, dissection and motion in direct relationship to his artistic output. In fact, some of his most famous works are those depicting the surgical amphitheater classrooms of that time period. Today he is considered one of the most significant American artists of the late 19th century.

Thomas Eakins’ interest in draftsmanship began at an early age, and like most serious American artists of the Victorian era, he eventually travelled to Europe for more formal training. Interestingly, he was not taken in by the loose brushwork and bright colors of the groundbreaking Impressionists. He was a traditionalist at heart, and his artistic focus was a sense of realism primarily based in scientific observation.

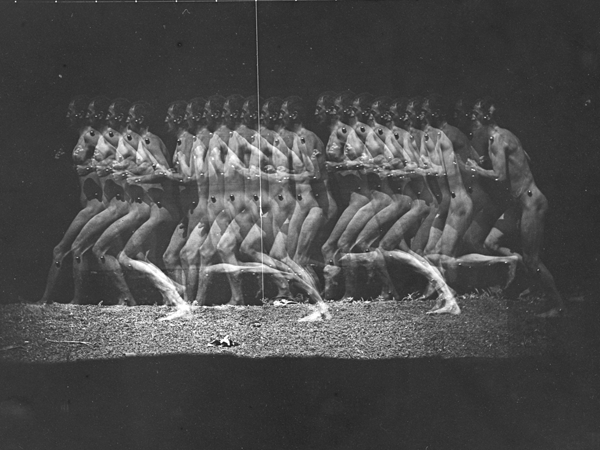

Eakins became a drawing and painting instructor at the Pennsylvania Academy, where he encouraged his students to use the new medium of photography in order to aid their own understanding of anatomy and motion. He, himself, was fascinated by the lingering information a photograph could provide an artist. For a time, he worked alongside Eadweard Muybridge, famous for his sequential photos of bodies and animals, and an early developer of moving pictures. Eakins’ particular interest in the human form, however, led the artist to go on to develop his own technique for taking multiple images of a body in motion and layering them in one single image. He felt seeing the images so close together gave a better understanding of actual movement. In fact, his work, “Motion study: Male nude metallic markers attached to his body, running to left, 1885” is much like images produced today – over a 100 years later – in gait analysis labs.

Thomas Eakins, Motion study: male nude, metallic markers attached to his body, running to left, 1885. Courtesy of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts.

It made sense for Eakins, who was an athlete himself, to marry his photographic techniques with his passion for sports in his oil paintings. The resulting images frequently show figures scantily clothed in a variety of physical poses. He painted rowers, wrestlers, and swimmers and amassed an enormous collection of photographic studies. As an example of the integration of his photographic studies with his artistic work, the “Biglin Brothers Racing” painting is a thoughtful and accurate portrayal of the physicality of sport. The curators of the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., where the painting is on exhibition, offer information on the painting’s composition and its social context:

In the decade following the Civil War, rowing became one of America’s most popular spectator sports. When its champions, the Biglin brothers of New York, visited Philadelphia in the early 1870s, Thomas Eakins made numerous paintings and drawings of them and other racers. Here, the bank of the Schuylkill River divides the composition in two. The boatmen and the entering prow of a competing craft fill the lower half with their immediate, large-scale presence. The upper and distant half contains a four-man rowing crew, crowds on the shore, and spectators following in flagdecked steamboats.

Himself an amateur oarsman and a friend of the Biglins, Eakins portrays John with his blade still feathered, almost at the end of his return motion. Barney, a split-second ahead in his stroke, watches for his younger brother’s oar to bite the water. Both ends of the Biglins’ pair-oared boat project beyond the picture’s edges, generating a sense of urgency, as does the other prow jutting suddenly into view.

Thomas Eakins, The Biglin Brothers Racing, 1872, oil on canvas, Courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington

Ultimately, his honest and unorthodox approach to teaching about the nude figure (giving men and women equal access) lost him his job and damaged his reputation. Time has healed that reputation and we now see the important advancements he made using our understanding of the human body in motion to inform the portrayal of the body in art.

For further information on the life and work of Thomas Eakins, please refer to the list below:

- Foster KA. Thomas Eakins Rediscovered. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press; 1997.

- Goodrich L. Thomas Eakins. Vol 1 and 2. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1982.

- Sewell D. Thomas Eakins. Philadelphia, PA: Philadelphia Museum of Art; 2001.

- Rosenheim JL. Thomas Eakins, artist-photographer, in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin. 1994-1995; vol. 52, no.3:44-51.

References

1. Thomas Eakins: Motion study: Male nude metallic markers attached to his body, running to left. Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts Web site. http://www.pafa.org/museum/The-Collection-Greenfield-American-Art-Resource/Tour-the-Collection/Category/Collection-Detail/985/coltype–Ephemera/mkey–433/pageindex–4/. Accessed January 26, 2015.

2. Thomas Eakins: The Biglin Brothers Racing. National Gallery of Art Web site. https://www.nga.gov/collection/gallery/gg68/gg68-42848.html. Accessed January 25, 2015.

Member since 2019 | JM14274

Member since 2019 | JM14274

NO COMMENT