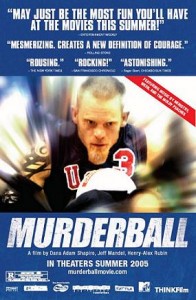

Murderball — Beyond the Documentary: Film Review and Analysis

By Katherine J. Voorhorst, SPT

History Lesson

Released in 2005, the documentary film Murderball ignited the nation’s interest in quad rugby, a high-octane version of wheelchair rugby. More importantly, the film has shed some much-needed light on the daily lives of those who have sustained spinal cord injuries. More than a great sports story, Murderball demands a certain level of respect that is inherent to watching any disabled person achieving something previously thought to be out of reach, like winning a gold medal.

Released in 2005, the documentary film Murderball ignited the nation’s interest in quad rugby, a high-octane version of wheelchair rugby. More importantly, the film has shed some much-needed light on the daily lives of those who have sustained spinal cord injuries. More than a great sports story, Murderball demands a certain level of respect that is inherent to watching any disabled person achieving something previously thought to be out of reach, like winning a gold medal.

The progression of events presented in the film reminds viewers that life goes on after an accident or disease interrupts the brain’s connection with the arms and legs. Murderball opens with paralympian Mark Zupan getting dressed for a workout. Zupan is presented at first as being just a guy going out for a jog around the block—in his wheelchair. The film follows Zupan and the United States quad rugby team as they train, compete, and unwind in the same way any able-bodied team would. They develop a fiercely natural rivalry with the Canadian team when Joe Soares, who was previously cut from the American team, becomes the head coach of the Canadian national team. Soares and Zupan have a mutual disdain for each other on and off the rugby court, which stirs a sincere sense of patriotism. Nonetheless, the film doesn’t ask you to choose sides. Instead, it asks that you consider each player individually as a piece of the quad rugby puzzle.

As viewers, we witness a change over the five years depicted in the film in the players, the venues, and the game itself. The most striking evolution takes place, however, in the secondary story of Keith Cavill, who sustained a spinal cord injury while racing motocross. He is representative of the majority of quad rugby players in that previous to his injury he had been independent and active. His role is crucial to the story presented in the film because his journey is applicable to those who have gone before, and those are yet to come.

Realistically Relevant

The increasing popularity of quad rugby has provided an outlet for many young men and women who have sustained spinal cord injuries. Some even say the game has saved their lives. Once an individual comes to terms with the fact that he (or she) will remain in a wheelchair, they have to make a choice about how they are going to rejoin the world. Zupan describes this process as a card game in which you play or you fold. Sink or float. For most of the young men on the court, quad rugby is the ultimate life preserver.

Front-Row Seat

Mark Zupan pushing with ball. Photo credit: Bob Long, usqra.org

One of the principal therapists presented in the film is Nancy Lehrer. Lehrer started her physical therapy career at Grady Memorial Hospital in downtown Atlanta, Georgia, where she has worked for over nineteen years (oral communication, September 8, 2014). She recalls how she benefitted from the teaching environment at her workplace, the significant autonomy she enjoyed as a clinician, and the experience she gained working with individuals from all walks of life. She spent approximately ten years volunteering with disabled athletes in and around the Atlanta area during the 1990s and early 2000s, including the time when Murderball was filmed.

Lehrer describes how her experience with quad rugby began: one day, she was sitting next to a physical therapist who worked at the Shepherd Center (a spinal cord injury rehabilitation center in Atlanta) and who also volunteered with the wheelchair track team. The two therapists began to talk about quad sports and their shared passion for this patient population. Eventually, she began volunteering with the track team training and helping with competition events. At a classification workshop designed to designate players to certain ranking based on the level of spinal injury, she found herself assigned, not to the track or road racing athletes, but to the quad rugby athletes.

These experiences seamlessly rerouted her to rugby practices, tournaments, and the World Wheelchair Games in 1999 with the U.S. National Rugby Team. She then traveled to the 2000 Paralympic games in Sydney, Australia. At that event, the U.S. defeated Australia to win the gold medal, much to the dismay of the Canadians, who captured the bronze. During this time Lehrer found that friends had become family, and she found as well that she was meeting people and seeing places she would not have encountered under other circumstances. Thus it was that she applied to travel with the team to the 2004 Paralympics in Athens, Greece.

Andy Cohn. Photo credit: THINKFILM, 2005

Her close interaction with the athletes and understanding the level of competition they can achieve has ultimately made her a better acute care therapist. She recognizes that there is no “crystal ball” to reveal a how and when along the road to recovery a patient may be able to achieve that type of rehabilitative success. “However,” she says of the hypothetical acute spinal cord injury patients, “when people are ready, we can share what life can still hold for them.” Her acknowledgement of a patient’s personal journey has allowed her to be more present as a therapist and has taught her that consistency is the key. Even if they are so down and frustrated with their condition that they are swearing you out of their room and have no desire to participate in therapy, you still have to show up the next day, let go of any ego, and encourage them to try again.

As the team travelled internationally, Lehrer continued to note cultural differences in the way the Paralympic athletes were treated. In the United States, people have a general naivety about those in wheelchairs; there is a learned “Us and Them” mentality that acts as a barrier to understanding them. Fortunately, she found this not necessarily the case with other nations. Lehrer described a time when the team travelled to southern New Zealand following the World Wheelchair games in 1999. The team received a warm welcome and signed autographs; it didn’t matter that they were in wheelchairs, it mattered that they had won gold.

The game isn’t about making it to the Paralympics or being on a professional team. It is about recruiting players and creating a shared experience that fosters a sense of belonging. “On the court it is competition and win, win, win,” says Lehrer, “but off the court we are friends and family.” The sport is about commitment, social support, bonding, and being the best they can be, just like any able-bodied sport. The film intentionally highlights that element of the story without neglecting where the players have come from and how they have moved beyond what is widely considered possible.

Tool for Teaching

“The frank honesty of the film has the potential to engage a class of students on a more intimate level as they learn about the personal experience of disability”

Dr. Tami Phillips and Dr. Laura Zajac-Cox are co-directors of Emory University’s DPT Adult Neurological Rehabilitation Complex. They agree that Murderball can be a valuable learning tool in the spinal cord injury (SCI) curriculum (oral communication, September 22, 2014). In previous years, the film was shown as an educationally inspirational piece before the DPT students embarked on their two-week neurological clinical rotations. Dr. Zajac-Cox is struck by the players’ aggressiveness and agility on the court, but more so by the film’s ability to highlight the players’ potential without the interference of any artificial limits. She feels the film raises the bar of understanding and highlights many moments that are difficult to include in a classroom setting. “They are normal guys socializing; they have normal cares and concerns,” says Dr. Phillips. Both professors feel that the medical and rehabilitation communities frequently fail to address the considerable ambiguity surrounding sensitive subjects like sexual function and driving capability that many neurological patients face once discharged. Murderball effectively and honestly presents both issues in a way that cannot be taught from a textbook or classroom discussion.

While Murderball was not meant to be an educational film per se, short video clips of interviews done with the players or of the game itself, would be advantageous supplements to classroom discussion. The frank honesty of the film has the potential to engage a class of students on a more intimate level as they learn about the personal experience of disability. Alternatively, the entire film could be incorporated into a neurorehabilitation syllabus as an outside assignment with subsequent classroom discussion and analysis. Regardless of the method, Murderball should be considered a multi-use tool in the educational tool box.

Murderball. Documentary, 86 min, rated R for profanity and sexual content. Available at: http://www.amazon.com/Murderball-Joe-Soares/dp/B000B5XP24

Interview with Director Dana Shapiro

by Sarah Blanton, PT, DPT, NCS —

Murderball’s director, Dana Shapiro, shared his reflections on the ten years that have passed since the movie’s premiere (oral communication, December 4, 2015).

“The film is not about rugby — it is about these men — they just happened to play rugby and they just happened to be quadriplegic”

In 2002, Dana Shapiro (at that time a senior editor at Spin magazine) took an interest in the subject of quad rugby when he read a character-driven newspaper article about the Phoenix Heat rivalry with Texas Stampede. He remembers how the Heat’s team members related with their trash talk and “in my ignorance, didn’t know they communicated the same way as my friends talking trash in the locker room.” He wasn’t aware of the difference between quadriplegics and paraplegics, noting, “I thought quadriplegic meant Christopher Reeves with a motorized wheelchair, using a vent, and sipping through a straw.” He realized that what he was encountering in the team’s stories were real stories about real men’s lives that had been changed in an instant. He became fascinated with the character development in that rise-fall-rise again journey, remarking that: “[e]very great sport story has its rivalry – USA and Canada, Frazier and Ali – and quad rugby had Zupan and Soares.” This competition and the fact that the characters were brutally honest, unedited, not afraid to be real, led Shapiro (and his colleagues Henry-Alex Rubin and Jeffrey V. Mandel) to spend the next two and half years following the U.S. team as it prepared for the ultimate showdown with archrival Canada at the 2004 Paralympics. Making the film far exceeded his expectations because “we became close friends, not just filmmaker and subject – there was a fluency between us because they allowed us into their lives.” Murderball became a labor of love, he noted: “we learned about them as friends just as we learned about them as filmmakers.” He reflects that he brought to the project an innocence, an ignorance which made the experience different than if a therapist had made it: “I think it helped the film because we grew ourselves as we made it, and most viewers would also come from that point of innocence and curiosity.”

Top Row: Rubin and Shapiro, Bottom Row: Soares, Zupan, Mandel. Photo credit: Jeff Vespa, WireImage.com, 2005

When asked when he started to feel comfortable around the athletes, he remembers it took nearly a full year before he could trash-talk them like his friends in the locker room and also before he realized they didn’t want doors held open. “I realized that best intentions could come across as condescending and realized they don’t need my help, they wanted a more realistic relationship. I stopped seeing the wheelchair and started seeing the person.”

With respect to the use of Murderball in the classroom, Shapiro hopes that the story of these men will help to humanize the medical condition for students. He feels that if a therapist is face-to-face working with these individuals, they really need to understand what it is like to break your neck: “How can you really have a conversation with someone if you don’t know where they are coming from? You don’t know what they are afraid of? What they are insulted by?”

Shapiro noted that “[t]he goal of a documentary is to learn what it is like to walk (or roll) in their shoes, to learn what it is like to break your neck, to have your world shattered. That experience infuses all of your opinion for the rest of your life. The film is not about rugby—it is about these men—they just happened to play rugby and they just happened to be quadriplegic.” Shooting over 200 hours of footage over two and half years, Shapiro quietly admits he was paid very little for this role: “What drives a journalist, a filmmaker is genuine respect—I was genuinely interested in their story. It was very rewarding. The best thing is when a newly injured individual says ‘because of your movie I want to try to become a rugby player.’ ” Certainly, now more people are aware of the Paralympics, and he hopes that individuals with quadriplegia will not feel their life is over, but see that inspiration lives on, that there is “a pin prick of light in the dark.”

About the Director, Dana Adam Shapiro

Dana Adam Shapiro was nominated for the 2006 Academy Award for his first film, Murderball. His second film, Monogamy, was nominated for a 2011 Independent Spirit Award. Shapiro is a former senior editor at Spin, and a contributor to The New York Times Magazine and other publications. His most recent book, You Can Be Right (Or: You Can Be Married) was published by Scribner in 2012. Shapiro produced and co-directed Murderball with his colleagues Henry-Alex Rubin (co-director and cinematographer) and Jeffrey V. Mandel producer).

Awards

The Sundance Film Festival Audience Award for Best Documentary, the Full Frame Documentary Film Festival Audience Award for Best Feature Film, the Indianapolis International Film Festival Audience Award for Best Feature and Best Non-Fiction Film, and a nomination for Best Documentary feature at the 78th Academy Awards.

Member since 2019 | JM14274

Member since 2019 | JM14274

NO COMMENT