Context is Everything

By Rebecca Gene Crockett

“If she were in the United States, things would be better for Cathrine, wouldn’t they?” her father whispered. There in Belize, on the opposite side of the small living room, his seven-year-old daughter with quadriplegic cerebral palsy was engaged in the bimonthly physical therapy session provided by an American non-profit. “If I can move her to your country, no one would leave her alone in a classroom; she would have a teacher who knew she wasn’t stupid; Cathrine would have more opportunity…” his eyes pleaded for hope. As much as I hated to acknowledge the injustice, her father deserved an honest answer: “The United States has not perfected schooling for children with disabilities either,” I began carefully, “But, yes, if you can move her to the US, in general, Cathrine would have more options there.”

Getting to Know the Human with the Disability

Citizens of developed nations have more opportunity than individuals living in developing countries. As a graduate student with a background in sociology and extensive travel experience, this really should not have been a revelation for me. Nevertheless, Cathrine’s dilemma challenged both my academic head and my sensitive heart. In that first week I spent in Belize, her father made me face the privileged guilt I wished I could hide from: my citizenship alone afforded me many advantages over the rest of the developing world.

Because many of the Mayans live in remote villages, Hillside brings the mobile clinic to them each month.

This emphasis on context and its effect on disability were not emphasized in my Doctor of Physical Therapy curriculum. My two years within the physical therapy program memorizing pathophysiology had proven dissatisfying; something was missing—the human with the disability. My long-term rotations had further highlighted that missing humanities piece. I found the most valuable time I had experienced with patients in the school system, outpatient clinic, and hospital involved not increasing strength or range of motion, but rather helping people re-integrate within society. Sometimes this meant modifying the actual environment, for example adapting a student’s physical education class. Other times I empowered the patient to better function in her context by equipping her with education and assistive technology or simply a more thorough discharge plan. But every notable success involved stepping back from the physical impairment and defining the disability in terms of the person in front of me. Seeking more insight into this holistic approach, I chose to pursue a dual DPT-MPH degree in Behavioral Sciences and Health Education at Emory University’s Rollins School of Public Health.

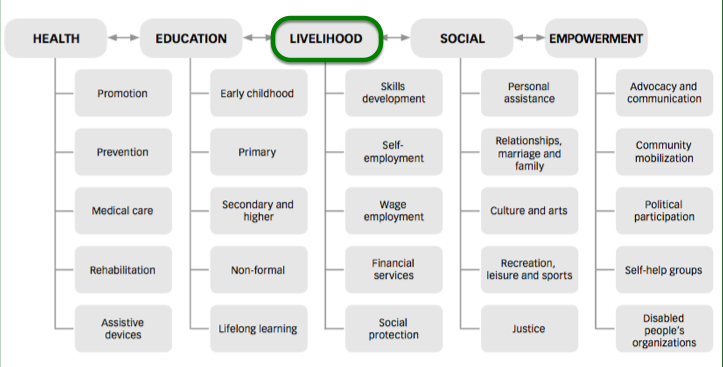

Looking for a way to combine my interests in PT and public health, I applied for a scholarship from Emory’s Global Health Institute (GHI) to travel to Punta Gorda, Belize in the summer of 2014. There, my long-term mentor Lori Northcraft Baxter, an Emory DPT-MPH alum, was serving as Rehabilitation Director at Hillside Health Care International and asked for help expanding the Rehabilitation Department to meet the livelihood needs of persons with disabilities in the community.1

Socio-Contextual Determinants of Disability

My early introduction to Cathrine showed me the devastating, lifelong consequences of starting one’s Belizean life with disability. Her mother had become quite ill during pregnancy, which likely was the etiology for Cathrine’s subsequent quadriplegic cerebral palsy (CP). CP is a complex health condition for citizens of a developed nation to comprehend. In a Mayan district where health literacy lags and folk medicine still prevails, such disabilities are best understood as a punishment for parents’ wrongdoing. This stigma surrounding CP often ostracizes the family from its extended relatives. That guilt, combined with the additional burden of caring for a child with special needs, often keeps families in the confines of their home where they can avoid the stares of community members who regard their child as strange at best, at worst a curse.

In addition to impeding family care, this stigma has also resulted in insufficient educational accommodations for students with CP. In the Toledo District, there are two Special Education classrooms for the entire district—both with one teacher responsible for juggling the individual plans and accommodations of each child with cognitive delay. Because Cathrine’s disability is mainly physical, she is ineligible for this setting; she is far too intelligent to qualify. In the larger mainstream classrooms, with no aides to assist the teacher, there is no one to provide the individual physical support for toileting and completing classwork that Cathrine needs to participate. Moreover, when the school grounds are not handicap accessible, the teacher may determine it easier to leave Cathrine in one room throughout the day—alienated from activities that take place in other classrooms and unable to interact with her friends at recess. Shunned by her extended family, isolated from her community, and underserved by her school, Cathrine has little hope for developing a vocation that consists of anything but “disabled.”

I had studied the World Health Organization’s World Report on Disability2 while applying for the GHI scholarship. But it was not until I met Cathrine that the words came alive: Cathrine was not only disabled by her CP; she was largely disabled by her context, by her society. In its most rudimentary form, the classification of disability refers to a health condition that prevents an individual from performing socially expected activities, namely working.3 I realized the most specialized home exercise program could not address the participation restrictions of contributing to society as a member of the workforce. The transformation from a child confined to home, destined to be a burden on her family members (disability), to active community member with an identified participatory role (ability) would require a structural change in special education—much more extensive than anything completed in her individual physical therapy session. This realization overwhelmed me, as did the fact that I was just a student limited in experience and time in Belize, a country with no explicit legal protection for those with disabilities. But I could not ignore Cathrine’s predicament or the hope that I could make a difference by advocating for her human rights to education and skills training.

An Action Plan Emerges

Bekka and long-term mentor Lori, then Hillside’s Rehab’s Director, determine the waters are too high to make it to this week’s mobile clinic.

With Cathrine as inspiration and the local Ministry of Education’s support, I focused on a subset of the population that evoked the most compassion—children with disabilities, blameless of any supposed wrongdoing. Through collaboration with parents of children with disabilities, the two Special Educators in the district, clinicians, government and nongovernmental officials, adults with disabilities, and an instrumental American educator named Amy Almond who shared my passion, an action plan emerged. In only ten weeks, we could not transform the health literacy of the Mayan villages; nor could we increase the education budget to allow for classroom assistants. But we could introduce the concept of skills training into the school system for children with physical and/or cognitive disability. The goal was to develop skill sets that could contribute economic value to individuals and their community, while simultaneously promoting community awareness of disability and interaction within the local population.

At the national conference for Special Educators in Belize City, Amy and I presented our plan to the National Resource Center for Inclusive Education (NaRCIE). Similar to the Transition Individual Education Plans (TIEP) in the United States, as a child finishes compulsory education, the Ministry of Education will use a predetermined plan to transition that student to the labor force. With help from specialized community members, this protocol will include on-site skills training. In this manner, students will develop a skillset and thereby cultivate a role and identity within their community. For some, that will translate to income that will assist their families. Even for those who cannot market their hand-made goods or services, the skills training can leave a sense of accomplishment and human dignity that surpasses any dollar value. Much to our surprise, the Ministry of Education unanimously adopted the action plan— effective immediately for the 2014-2015 academic year. Furthermore, in the near future, NaRCIE’s lead representative in the Toledo District agreed to partner with Hillside to develop this program and extend its resources to the adult population with disabilities.

Leaving an ‘Uus’ PT

‘Uus,’ which in Ketchi means good or better, is still my favorite word my Mayan patients taught me. In fact, while I had been focused on how to improve Southern Belize’s perception of physical disability, I could not anticipate the internal transformation and professional growth that would also take place within me; I left Belize a better physical therapist. I once thought I would help others overcome their disability by addressing their physical impairments, acting on the individual level (e.g. addressing Cathrine’s muscle contractures). In the summer of 2014, a seven-year-old girl with CP taught me that a person’s role in society is not only determined by the ability to use her arms and legs; that ability to participate is also determined by society itself. To help Cathrine overcome her disability as a person with little hope of societal participation, I had to address the impairments of the policy and bureaucracy around her.

As I finish my training to be a PT, I recognize how directly this message translates to my initial evaluations; just as important as establishing individual goals for strength and transfers will be the need for me to identify and address societal barriers that exacerbate the disability. For each person, this context will vary and may require her healthcare team to wear hats outside the realm of their educational preparation, including political hats they loathe. Nevertheless, this holistic mindset is essential if we hope to truly overcome disability. Because theoretically, ideally place should not determine opportunity—not for Cathrine or anyone else.

References

1. Community-Based Rehabilitation Guidelines. World Health Organization Web site.http://www.who.int/disabilities/cbr/guidelines/en/. Accessed February 2014.

2. World Report on Disability. World Health Organization Web site. http://www.who.int/disabilities/world_report/2011/en/. Accessed February 2014.

3. Nagi S Z. Disability and Rehabilitation. Columbus, OH: Ohio State University Press; 1969.

Member since 2019 | JM14274

Member since 2019 | JM14274

NO COMMENT